5. Jodorowsky’s Dune (Frank Pavich, 2013)

Like Brian Wilson’s “Smile” or like Kafka’s “The Castle”, the unfinished and unpublished “Dune” by Alejandro Jodorowsky turned into one of the most mystical unreleased films.

One of the most ambitious projects ever had an ensemble cast included Orson Welles, Salvador Dali, Pink Floyd, and David Carradine, all of them acceding to appear on the film.

Jodorowsky planned every detail and wanted his film to be a transcendental experience, changing people’s consciousness. We will never know if he was capable of such an exaggerated concept, with “Jodorowsky’s Dune” leaving a document proving that he at leasttried, and he tried hard. He contacted an incredible group of visual artists and they worked in a totally detailed storyboard of the film.

Collaborating with Moebius, Jodorowsky finished a detailed art book explaining what the film was going to be, a book that was rejected by every Hollywood studio.

Pavich’s documentary tries to makes us imagine how the film was going to be, helping our minds with some animated segments and a detailed journey through Moebius’ ideas. The documentary works as a discussion on the nature of film, showing a tired director trying to make a project too great for Hollywood’s standards.

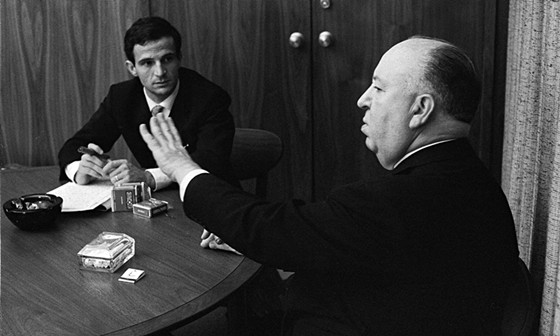

4. Hitchcock/Truffaut (Kent Jones, 2015)

One of the most influential books on cinema history is taken as the basis to reunite different directors of the world to talk about Hitchcock. When Godard, Chabrol, Rivette, Truffaut and other geniuses of French cinema wrote under the wing of André Bazin for Cahiers du Cinéma, the made several articles appreciating American directors, and calling some of them auteurs.

This concept defined a director as the mastermind behind a film, and any film by an auteur, even a bad one, had something to say and compliment about their worlds. The screenplay provided only the narrative, because behind all the artistic decisions there was a mind that defined something more important for a film.

The French writers, and especially Truffaut, recognized this on Alfred Hitchcock above everyone. Hitchcock was the master who crafted filmmaking as an art expression, and this art expression was explained by himself to Truffaut in 1962.

The influence of the book is seen in different interviews with Martin Scorsese, Richard Linklater, Olivier Assayas and Kiyoshi Kurosawa, among different directors. Every one of them describe the profound impact that Hitchcock’s way had in their own way to interpret the film craft.

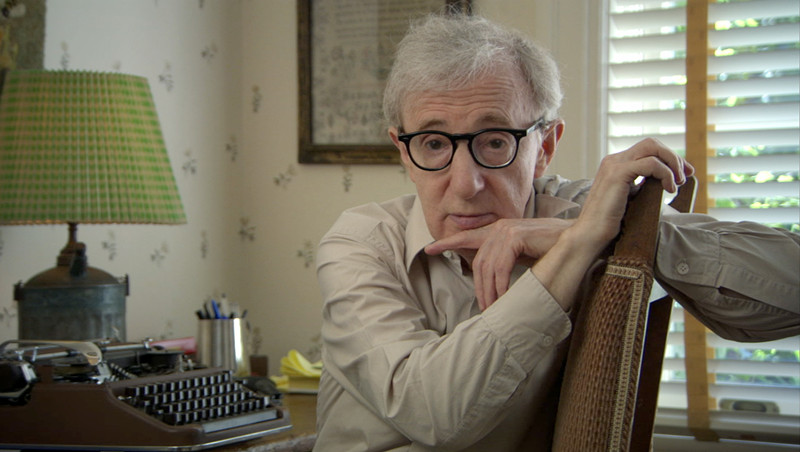

3. Woody Allen: A Documentary (Robert B. Weide, 2012)

Robert B. Weide’s documentary is all we want to see when we see its title. It doesn’t present a fresh narrative, but it gives us all the information we want about Woody. How much of Woody do we see in his characters? This constant question is raised in every Woody fan.

His relationship with actors, his mannerisms, his paranoia, his sometimes turbulent relationship with women, every question that everybody raises about Woody’s life is asked in depth on Weide’s film.

It is the first time that Allen gave free access to his private life and filming, the film provides all the missing information, including an insight to his childhood and stand-up comedy shows, as well as his life as a writer outside his films and his participation in jazz bands. All these well-known elements about his life are finally examined by himself in “Woody Allen: A Documentary”.

2. How Strange to be Named Federico (Ettore Scola, 2013)

Scola’s loving tribute to his longtime friend Federico Fellini is hardly a documentary. It is hardly a fiction, and it is hardly telling us the truth. But how does one make a straight tale, a coherent story on someone like Fellini? Scola talks about Fellini in the way his closest people defied him: the biggest liar of all time.

With this big lie of cinema and life on his mind, Scola made a film that jumped chronologically, and that doesn’t make any distinction between a reenactment and archive footage. But we still learn a lot about Fellini’s life, and you can see how the subjective portrayal of Scola is truly sincere.

We see that Scola practically shaped his life according to Federico; he wanted to be a drawer after reading his comics, and he discussed his first ideas of films while Fellini was making it at Cannes.

Unlike most of documentaries about artists that are chronological expositive telling, Scola’s version is completely personal and you can see traces of an auteur. His imitating of Federico’s style, but the imprint of his own is all around the film. The film has been accused of being a collage, a non-coherent tale of Fellini, but it is the way Scola’s memory works.

It jumps from one event to another, and Fellini’s films are not different to life. There is a beautiful scene with Fellini and Scola talking in a car (a reenactment, of course), and the background city comes from a scene of Fellini’s “Rome”. The effect is poorly made, but that’s the idea; there is an actual collage of Fellini’s life mixed with his films and dreams.

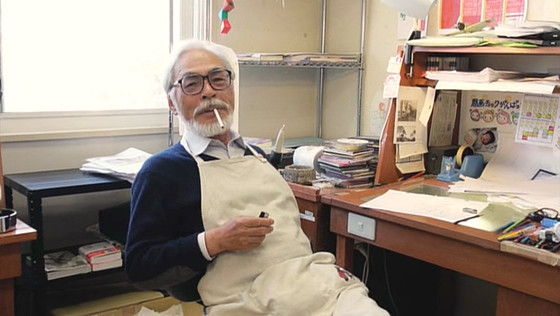

1. The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness (Mami Sunada, 2013)

Thanks to different films and documentaries, the mystery of filmmaking is not completely foreign to the audience. But animation remains a mystery practically to everybody who didn’t make an animated film. Mami Sunada’s beautiful documentary gives a deep look at the work inside Studio Ghibli.

A weird case of a traditional animation studio with worldwide success. Sunada doesn’t make a chronological trip through Hayao Miyazaki’s and Isao Takahata’s life, and makes instead a much richer and interesting journey through a normal month of work inside Ghibli.

The big differences between the methodic Miyazaki, and the untidy Takahata shows two different approaches to one of the most dedicated forms of art. We discover how much time it takes to make an extra character walk around the city, and how hard can be to work for someone like Hayao Miyazaki.

Sunada shows us the strange conflict between running a business and doing something so difficult to profit at the same time, and the bitterness lying inside of that clash. There is a hopeless attitude in Miyazaki’s view, and we don’t get a lot from Takahata’s way of work.

It’s about the affable and wise old man, and the even older and elusive master. “The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness” is not a straight documentary to learn a little bit a studio’s history, but something much deeper. The film reflects on animation as an art form, and how neoliberalism is difficult to match with it. The end of Ghibli is also the end of a way of looking at art.