5. “I am not an animal, I am a human being!” from The Elephant Man

This timeless classic and academy award nominated drama is one of the few examples of Lynch’s works that attained mainstream recognition. Exploring the difficult and true life of John Merrick (John Hurt), a sufferer of a rare condition that left his entire body covered with tumours, The Elephant Man strays far away from Lynch’s signature surrealistic style.

There are elements of this auteur’s finest strengths peppered throughout, however, such as images of grinding machinery in high contrast and a sound design evocative of industry and a ubiquitous sense of foreboding.

Perhaps the most noteworthy facet to this movie is the acting: from John Hurt’s heart-wrenching, graceful portrayal of Merrick, to Anthony Hopkins’ curiously altruistic and guilt-ridden performance as Frederick Treves.

In this iconic scene, Merrick is meandering clumsily through a crowded London train station, attracting the glares and vicious intrigue of bystanders. They begin to form a mob from which he attempts to flee, but before long they corner him. Merrick experiences sensory overload – brilliantly orchestrated by the imposing score and frantic mis-en-scene – and breaking down, exclaims, “I am not an animal, I am a human being!”

Shattering the preconceptions of both the crowd and the audience, Merrick finally shows his mettle after a lifetime of being abused into silence and John Hurt’s dignified, yet troubled performance in this scene boldly declared its place in the history of cinema.

4. “Baby Wants Blue Velvet” from Blue Velvet

As mentioned in the previous entry, Dennis Hopper’s portrayal of Frank Booth in Blue Velvet is a powerhouse of terror and vindictiveness. This scene is when the audience is first introduced to this walking contradiction of depravity and sexual vulnerability.

Jeffrey – serving as the audience’s eyes – is hiding in Dorothy’s closet, peering through a crack to watch the horror unfold as Frank manipulates and abuses her. Lynch uses wide-framed shots that draw the audience’s attention to the hues of red walls juxtaposed with Dorothy’s blue dress, evoking an abstract undercurrent of calmness and serenity fragmented by the impending danger of this mysterious man.

In a dark subversion of expectations, Jeffrey (and vicariously, the audience) witness Frank’s unusual sexual proclivities, such as inhaling from a non-descript gasmask, referring to himself as “Baby” and conversely “Daddy”, and dry-humping and assaulting Dorothy.

Frank climaxes in a fit of rage and pleasure, leaving Dorothy to lick the wounds. These bizarre practices form to paint a picture of a man projecting childhood fears and trauma through sadomasochistic indulgences, of which Dorothy is both the prisoner and victim.

This highly provocative and controversial scene would forever be imprinted in the movie-goers mind, making it one of Lynch’s most powerful and disturbing moments committed to celluloid.

3. Rabbits from Inland Empire

Pageantry and affectation are themes that are often played around with in Lynch’s work and Inland Empire is a great example of these ideas being executed and subverted as narrative devices.

Whether you remember this film for its impenetrable dialogue and structure or its stylisation reminiscent of a documentary, you’ll certainly recall this bizarre scene. In it, a family of rabbits are gathered in a living room, participating in stilted small talk over an ominous, sub-bass hum that hovers dangerously close to the infamous ‘brown note.’ Not really, but it’s disturbing nonetheless!

Taken from a web-series of the same name, “Rabbits” is presented as a shallow, four-walls multi-camera sitcom ostensibly designed to satirise the artifice and emotional manipulation of the medium: complete with canned audience laughter to really hammer home the message!

2. ‘In Heaven’ from Eraserhead

Eraserhead is iconic for its excellent sound design and Lynch’s near-decade commitment to production: fraught with time constraints, monetary woes and a severe lack of studio support (not to mention the insufferable caterwauling of a deformed baby in distress).

In perhaps one of the most memorable sequences in Lynch’s debut effort, protagonist Henry (played by the late, great Jack Nance) pierces through the veil of reality and into a radiator: in which a spotlight illuminating a stage reveals a strange and sinister musical performance.

The inconceivably conceived Lady in the Radiator (Laurel Near) steps to the microphone and softly chimes the words “in heaven, everything is fine” between ostensible mouthfuls of cotton wool (or tumorous masses).

The haunting cadence in her voice and minimalistic lyrics capture the dream-like aloofness of Henry’ submission to the sweet release of death and this scene in particular cemented Lynch’s legacy as a surrealistic, audio-visual artist.

1. Winkie’s Diner from Mulholland Drive

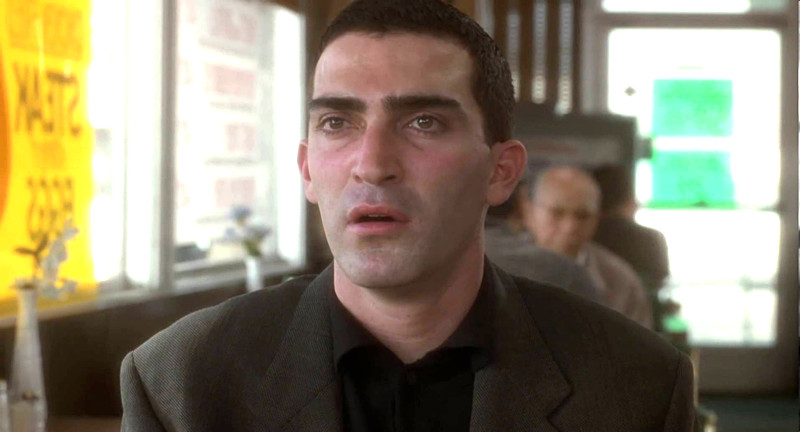

The monster lurking behind the diner is a striking moment in Lynch’s psychological thriller masterpiece.

In this temporally confusing scene, two friends are sitting together in a diner that one observes is exactly like it is in his recurring nightmare.

He proceeds to describe the dream and how, in it, he witnesses a monster behind the diner that has haunted him ever since. His friend insists that they investigate and the sequence thus plays out exactly as he described, causing him to faint and the movie to transition into a seemingly unrelated sequence of events.

Manipulating the audience’s expectations through unnerving sound design, naturalistic lighting and a curiously banal mis-en-scene, Lynch slowly peels back the layers of the dreamscape, revealing a sinister presence that would both permeate throughout the film and mystify the uninitiated viewer.

Author Bio: Conor is a screenwriter, musician and self-ascribed pop-culture savant with a BA degree in Film and Television Production. He uses his spare time to create YouTube content and write music as an independent artist.