5. Vinyan (Fabrice du Welz, 2008)

Everyone remembers that moment in “Apocalypse Now” when Martin Sheen’s character first sees the natives, looking at him with their unexplainable otherness. “Vinyan” reprises this theme through the story of a Western couple who lose themselves in Thailand, as the desperate search for their son leads into a realm of criminality and the supernatural.

The cinematography alternates tones of green and tones of grey, and the constant rain adds an element of relentless sorrow to the film, which makes it comparable to Bayona’s “The Orphanage”.

It is a reflection on the power of grief and how it shapes lives, and above all, it’s a film about the body and how emotion relates to the body, and how the woman symbolizes nature, the uncontrollable powers, the madness of nature, and how the man, in his stability, is bound to succumb to her power.

Primordial energy that comes from grief and loss, that comes from the jungle, the shadows, the rain, and the trees, are the weapons of horror and chaos, and the reason why the jungle is still so scary in horror tradition, as it is the place where the uncontrollable forces reign, where the spirits rule.

4. Jigoku (Nobuo Nakagawa, 1960)

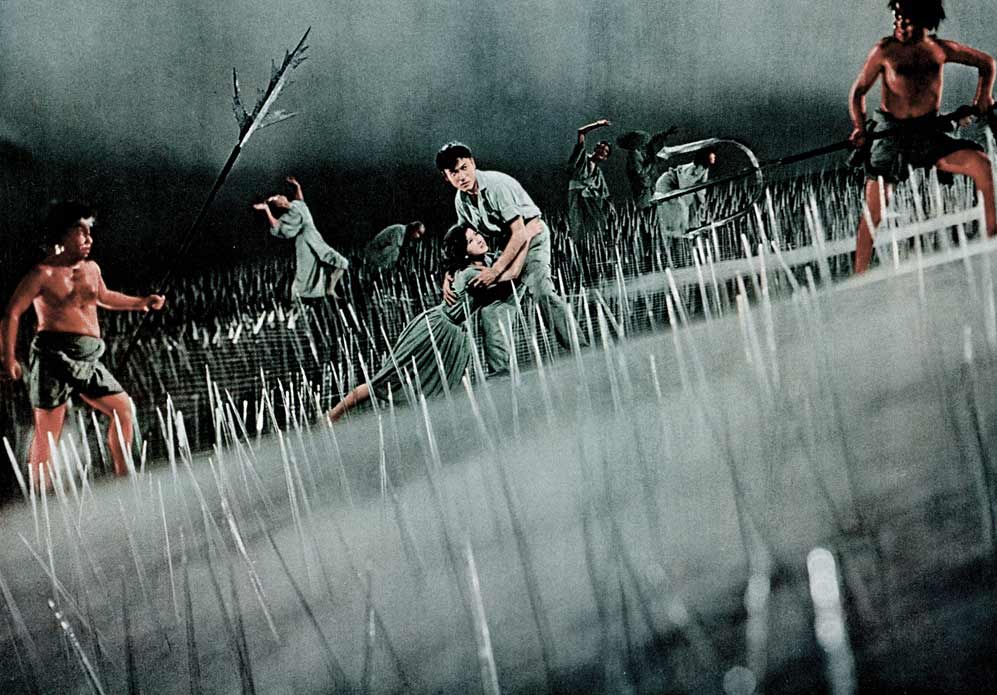

The 60s were a particularly prolific time for Japanese horror cinema, from Kaneto Shindo’s “Onibaba” and “Kuroneko”, to Masaki Kobayashi’s “Kwaidan”, but “Jigoku” had something that none of the others had: a clear philosophical vision, and a serious reflection on the nature of fear and sin, along with one of the most memorable visions of hell in the history of horror cinema.

The third act of the film, which takes place in the underworld, mixes the theatrical sensibility of Japanese tradition with ethereal and surreal cinematography, audacious camera movements, and choices of representation, and it is deeply symbolical as it is not only a series of infernal visions, splatter moments, and abstract tortures that the characters have to endure, but rather a sequence that has an arc that leads to redemption, as the nature of hell in the film is not static, but progressive.

In Western tradition, hell is definitive and inescapable, but in this Japanese film, one can find a way through hell, as the end of the film is more infused with serenity than with torment.

To Nakagawa, hell concerns not only the dead but the living as well, as everyone carries personal demons and tragedies that are surpassed in order to find appeasement. The abstract sequences work on two levels, the fantastical and the psychological; the soul of the protagonist is faced with much more than horrid visions of damnation, but also with the small damnations that occupy everyone’s life and have to get cast out of our soul in order to complete the cycle of a life.

3. Marebito (Takashi Shimizu, 2004)

At first sight, “Marebito” is a typical film of the Japanese new wave of horror films that peaked at the end of the 90s and the beginning of the 2000s. The classic notions of voyeurism, the postmodern take on video, and the souls that manifest as bloodthirsty ghosts (usually as little girls) all symbolize a loss of innocence; death in his most candid incarnation.

But what is the underground world in which the film descends? Is it another Lovecraftian series of images, the fears of humanity made physical, the abstract that becomes material, those from the outside that are unleashed from their prison and invading the known world? Maybe this is what the Deros are.

Also, playing a major part in the film is the sense of urban paranoia, the filthy splendor of Japanese society, and what is underneath it. Lovecraft, sci-fi fiction, and to some extent, Gilles Deleuze and his concept of “Rizoma”, show the philosophical state of matter where all the things are intertwined, what is under the surface.

The power of “Marebito” comes from the imaginative force of the direction, from the ability to give life to complex metaphors and propose them in a physical and dramatic form, a horror film that is concerned with the greatest philosophical discourses of the last century, as well as folk horror and social commentary on the state of Japan as a whole.

2. In the Mouth of Madness (John Carpenter, 1995)

What is real? What is this darkness that we all feel? From Lovecraft to negative philosophy to gothic literature, John Carpenter put all of his pop sensibility into making the last film in the Apocalypse Trilogy, after “The Thing” and “Prince of Darkness”.

If “Prince of Darkness”, an unashamedly metaphysical film, was a bit more cryptic, experimental, and arrhythmic in its nature, “In the Mouth of Madness” is much faster in its development, and has a structure that is influenced by pulp literature and Italian Giallo.

The film is a post-LSD vision of reality crumbling; a character that is so sure of his perception of reality that he’s driven insane by the discovering of the monster of the unknown, of the materialization of the unspeakable abyss that is made flesh by the pages of the book, that terrifyingly evokes monstrous visions. The writer is the creator, but if the writer is the creator, is reality an invention?

Maybe it is all an invention. In the last, meta-cinematic trick of the film, the protagonist goes to a cinema, to watch “In the Mouth of Madness”, directed by John Carpenter. The author itself is a construct, and humanity will become a fairytale when the monsters take over, the monsters symbolizing the inscrutable darkness of infinity that is going to swallow us one day.

1. Inland Empire (David Lynch, 2006)

“Life is constantly strange, it’s everywhere.” These are more or less the words of David Lynch that resumes his cinematic poetry and his approach. “Inland Empire” can be seen as many things, and one of these things is a horror film. The theme of the cursed Polish movie seems to wink at some canonic plots that have made the genre famous, especially in the early years of cinema, where the obsession with the supernatural and the gothic were explored incessantly.

Early cinema constitutes the backbone of Lynch’s style, and in “Inland Empire”, he mixes early 1920’s expressionism, surrealism, and old school American and British horror to produce what currently is his latest film.

Lynch does much more than just let his camera penetrate into the subconscious and the sunken level of reality; he articulates his vision, and he constructs a building of sensations, angles, and nuances to the variety of obsessive details, involuntary compulsions that torture the psyche of an individual and infest reality with the appearance of a sinister ghost.

This film, made up of familiar streets, familiar details, haunted mansions, and giant rabbits is not a brakeless fantasy, or a flight of the imagination; it is, like Lynch has stated multiple times, a very realistic story, maybe one of the realest Lynchian films, one that is so focused on examining through a surrealist lens that the boundaries are broken completely.

In “Inland Empire”, Lynch operates a great destructuralization on the invisible walls that create our perception of the real, all rooted in his postmodern sensibility that make him a master of doubt, of things crumbling underneath, a constant in his film. He manages to build a world that is on the fringe, a connection between the real and the unreal. There’s much, much more going on the film than hauntings and satirical looks at the state of Hollywood.

Author Bio: Gabriele is an Italian film student studying in Scotland. He is an experimental and arthouse cinema enthusiasta and a believer in the crucial importance of freedom of artistic expression.