10. Little Miss Sunshine (2006)

This film was directed by husband and wife team, Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris. After their success with Little Miss Sunshine, the couple went on to direct the 2012 romantic comedy-drama Ruby Sparks, which was also met with a positive critical consensus. The two met at the UCLA film school in the 1970s. As a pair, they have directed and produced music videos, documentaries, commercials and films. Though released in 2006, the pair began work on the film in 2001.

The film won the Audience Award at the 2006 Sydney Film festival and an ovation at the 2006 Sundance Film Festival. The film was also nominated for four Academy Awards, including Best Picture, and won two: Best Original Screenplay for Michael Arndt and Best Supporting Actor for Alan Arkin. It also won the Independent Spirit Award for Best Feature and received numerous other accolades.

Despite tackling death and dysfunction, this indie comedy drama radiates warmth and charm. Greg Kinnear is wonderfully woe-begone as the success-obsessed patriarch leading his family cross-country in order to enter daughter Olive (Abigail Breslin) into a junior beauty pageant. Steve Carell is equally funny as his suicidal brother-in-law, swapping the wide-eyed innocence of The 40 Year Old Virgin for world-weary angst. Toni Collette is underused as Mom, but this combustible mix of characters still fuels a laugh-a-minute road trip.

It’s an assured debut for co-directors Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris, who benefit from a sharp and sensitive script by Michael Arndt. Even as Richard (Kinnear) scolds little Olive for eating full-fat ice cream, he draws sympathy as a man who dreams big and ends up feeling small. The humiliation of devising a nine-step plan for success that nobody wants to buy is bad enough, but then he’s pulled over by a porno-sniffing traffic cop in a scene to induce both laughter and cringing.

Occasionally the comic incidents feel a little jarring and clunky, such as Richard’s attempt to stash a dead body which stops just short of Weekend At Bernie’s. Generally, however, the story unfolds with a winning blend of sophistication and silliness. Dayton and Faris boldly satirize traditional American values without the easy cynicism – hilariously encapsulated by Olive’s precocious posturing at the beauty contest. More importantly, as the Hoover clan gradually get to know one another, the journey becomes fully engaging and oddly poignant. It definitely leaves one with that feel-good glow.

9. The Lives of Others (2006)

Film director Florian Maria Georg Christian Graf Henckel von Donnersmarck combined his talents and studies to bring a subtle film about the dangers of tyranny. Von Donnersmarck holds a Master of Arts degree in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics at New College, Oxford, and a diploma in Film Directing from the University of Television and Film of Munich.

In addition to The Lives of Others (in German, Das Leben der Anderen), which won the 2007 Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, Von Donnersmarck later directed The Tourist (2010), staring Angelina Joie and Johnny Dep.

Von Donnersmarck spent three years writing, directing and completing The Lives of Others. He has stated that the idea for the film came to him when he was trying to come up with a scenario for a film class. He was listening to music and recalled Maxim Gorky’s saying that Lenin’s favorite piece of music was Beethoven’s Appassionata. Gorky recounted a discussion with Lenin:

And screwing up his eyes and chuckling, [Lenin] added without mirth:

But I can’t listen to music often, it affects my nerves, it makes me want to say sweet nothings and pat the heads of people who, living in a filthy hell, can create such beauty. But today we mustn’t pat anyone on the head or we’ll get our hand bitten off; we’ve got to hit them on the heads, hit them without mercy, though in the ideal we are against doing any violence to people. Hm-hm—it’s a hellishly difficult office!

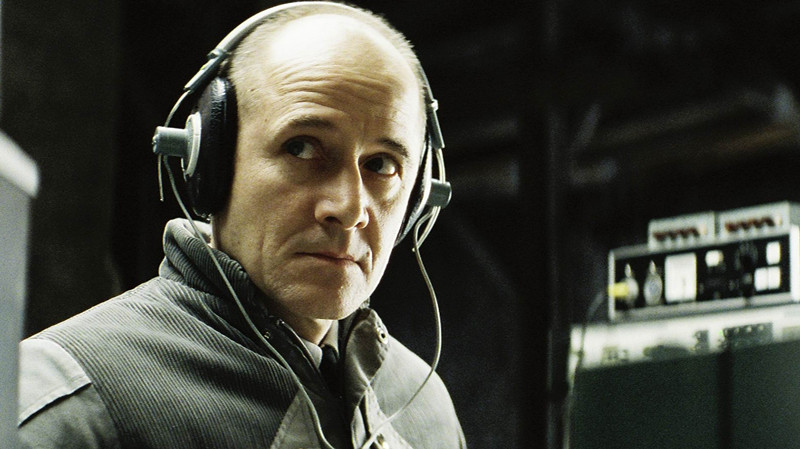

Donnersmarck told a New York Times reporter: “I suddenly had this image in my mind of a person sitting in a depressing room with earphones on his head and listening in to what he supposes is the enemy of the state and the enemy of his ideas, and what he is really hearing is beautiful music that touches him.”

Von Donnersmarck set his film in the East Germany of 1984, five years before the Berlin Wall collapsed. It was a time when the terrifying Stasi, the secret police, made it their business to use an extensive network of spies and surveillance to know every secret thing about their citizens.

Unlike other German films, most notably 2004’s landmark Goodbye, Lenin, Lives of Others is hardly an exercise in what’s called “Ostalgia”: nostalgia for the good old days of the East. Instead it is an inside look at how a surveillance society, set up to discover and prey upon human weakness, has the ability to make everyone a potential suspect and destroy everything it touches.

As the film’s intricate plot unfolds and the acting takes hold in the most vivid way, as the line between survival and self-destruction becomes hard to see, the story’s protagonists play increasingly dangerous double and triple games with each other.

There is a bracing, old-fashioned quality to Mr. von Donnersmarck’s film, which supplies us with good guys to root for and villains to despise. But it also shows, with excruciating precision, the cruelty with which a totalitarian state can exploit the weakness and confusion of its citizens. And even as they are, to some extent, enacting a morality play, the actors also seem like real, vulnerable people forced into impossible choices. This is especially true of Ms. Gedeck, whose natural nobility — her height, her carriage, the strong line of her jaw — makes Christa-Maria’s half-hidden fragility all the more poignant.

The suspense comes not only from the structure and pacing of the scenes, but also, more deeply, from the sense that even in an oppressive society, individuals are burdened with free will. One never knows, from one moment to the next, what course any of the characters will choose. Mr. Mühe conveys Wiesler’s curious evolution with appropriate meticulousness and reserve. It is only in retrospect that one appreciates the depth and subtlety of emotion that underlie his performance.

A terrible sadness lies at the heart of The Lives of Others — a reckoning of lives and talents wasted by a state with no good reason to exist apart from the maintenance of its own power. But there are comic, even farcical elements as well: a dictatorship that calls itself a democratic republic is inherently ridiculous as well as malignant.

Of course, today we know in advance the punch line that history will deliver in the autumn of 1989. But the easy, complacent distance that informs much historical filmmaking is almost entirely absent from this supremely intelligent, unfailingly honest movie.

8. Synecdoche, New York (2008)

Synecdoche is the fascinating directorial debut of Charles Stuart “Charlie” Kaufman, author of such philosophical and psychological comedies as Being John Malkovich, Adaptation and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

Impenetrable, cryptic, demanding, depressing, confrontational, self-indulgent: all these and more were used to describe Synecdoche. One needs no better reasons to see this film. That being said, without the right people, the film would likely have been completely lost on the right audience. Kaufman was blessed with a brilliant cast – Philip Seymour Hoffman, Samantha Morton, Catherine Keener, among many others.

The basic story concerns Hoffman’s theatre director getting a massive grant which he uses to build a replica of New York in a colossal warehouse, where his players perform their scenes behind closed doors. This leads on to plays within plays and blurred lines between fiction and reality, and to push it further out there, Kaufman plays with time, speeding up its passage as the decades roll away and Hoffman becomes more decrepit and lost.

The film is either a masterpiece or a massively dysfunctional act of self-indulgence and self-laceration. It has brilliance, either way: surreal, utterly distinctive, witty, gloomy in the manner that his fans will recognize and adore, but with a new epic confidence. Kaufman has absorbed the earthy fantasy and baroque images of Federico Fellini and combined them with the ironic banality that informs the films of David Lynch.

The film’s emotional intensity and ambition goes beyond anything done in Kaufman’s pevious films. Note in particular the extraordinary final sequence, in which the dying hero is instructed what to think and do, via a voice through an earpiece, while he stumbles through the wrecked stage-set of his self-created existence.

Kaufman proposes a theatrum mundi of his own. Philip Seymour Hoffman plays Caden Cotard, a miserable and hypochondriac theatre director living in Schenectady, New York, a place-name that whimsically mutates in the title, though nowhere in the script, to that obscure literary-critical term “synecdoche”, meaning an image in which the part stands for the whole.

The film at this point enters on metaphysical, epistemological and eschatological matters as Caden purchases a giant New York warehouse large enough to contain a sizable airship (at one point a zeppelin flies over Manhattan) and engages an army of actors to perform his work in progress. He marries, separates, attends his parents’ funerals, changes the subject of his magnum opus and reconstructs his life in the warehouse, with another actor (Tom Noonan) playing him. He’s getting old; after 17 years, the play is still not ready to come before an audience.

Caden’s existence and his play become coterminous, the enormous set taking in both meanings of synecdoche. The movie is at various times intriguing, funny, disturbing, eerie and occasionally irritating. Is life a dream as the Spanish playwrights thought? Is everyone the hero of their own drama and an extra in everyone else’s? Are we all sad Willy Lomans, doomed to failure? Is the only drama a short journey from birth to death over which we have no control?

Often regarded as one of the finest screenwriters of the 21st century, Kaufman has been nominated for three Academy Awards: twice for Best Original Screenplay for Being John Malkovich and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (winning for the latter), and Best Adapted Screenplay (with his fictional brother) for Adaptation. He also won two BAFTA Award for Best Original Screenplays and one BAFTA Award for Best Adapted Screenplay. Three of Kaufman’s scripts appear in the Writers Guild of America’s list of the 101 greatest movie screenplays ever written.

7. District 9 (2009)

Neill Blomkamp, director of District 9, is no stranger to the science fiction genre. In the late 1990s, he started working in the film industry as a 3D animator. His animation credits include Stargate SG-1 (1998), First Wave (1998), Mercy Point (1998) and Aftershock: Earthquake in New York (1999). After District 9, he would go on to direct the dystopian science fiction film Elysium (2013).

The film is an adaptation of Blomkamp’s earlier short film Alive in Joburg. It was named one of the top 10 independent films of 2009 by the National Board of Review of Motion Pictures. The film received four Academy Awards nominations, seven British Academy Film Awards nominations, five Broadcast Film Critics Association nominations, and one Golden Globe nomination.

In District 9, Blomkamp depicts humanity, xenophobia, and social segregation. The title and premise of District 9 were inspired by events in District Six, Cape Town, South Africa, during the apartheid era. That Blomkamp was born and raised in South Africa, and that the film was shot in South Africa, should make the allegory in this sci fi film nearly obvious.

Not too far into the future, a huge, lumbering spaceship shows up over planet Earth and stops there in the sky, hovering over a 21st-century modern city (Johannesburg). Terrified and suspicious, our earthling military finally storm the ship to find thousands of crustacean-like alien refugees cowering in the dark, metallic hold, evidently rejected by their home planet. Progressive liberal politicians have no choice but to allow these poor creatures out and let them live in the outskirts of the city, which they turn into a no-go crime slum called District 9.

They are nicknamed “prawns”, hated by civilians, police and army. Eventually a smarmy civil servant, Wikus van de Merwe, played by Sharlto Copley, is tasked with overseeing the mass eviction of the rabid untermensch-aliens, backed by the privatized corporate security militia, and moving them into a huge internment camp outside of town.

Copley’s performance is tremendous – particularly when he gets up close and personal with the alien prawns, a fatal transgression that is to trigger horrible changes in his own body. The sequences showing his impossibly dangerous sortie into the slum, which he carries off with a bizarre nonchalance indicating that he simply doesn’t understand the danger, are hugely tense with some grisly moments.

The film was shot on location in Chiawelo, Soweto, presenting fictional interviews, news footage, and video from surveillance cameras in a found footage format. Mimicking real life, the location was in fact a real impoverished neighborhood from which people were being forcibly relocated to government-subsidized housing

The DNA of action-sci-fi merges with a sleek exo-skeleton of satire to create a smart dystopian movie, excitingly shot in a docu-realist style with some stunningly real CGI work. It’s a film in the tradition of Planet of the Apes and Godzilla, with hints of serious pictures such as Children of Men and the less serious Cloverfield.

The film emphasizes the irony of Wikus becoming more humane as he becomes less human. Blomkamp ushers moviegoers into a brutal, ugly world that, for all the aliens running around, feels sadly familiar. It holds echoes of some of humanity’s most shameful, legalized crimes against itself: Blacks in apartheid-era South Africa; Jews in Nazi Germany; Native Americans in the early years of the United States.

History shows us how frighteningly easy it can be to marginalize people who look or act differently from us. Substitute ‘black,’ ‘Asian,’ ‘Mexican,’ ‘illegal,’ ‘Jew,’ or any number of different labels for the word ‘prawn’ in this film and you will hear the hidden truth behind the dialogue.

District 9 is not religious. It’s not spiritual. If the filmmakers in any way intended these biblical parallels, they keep evidence of it mostly under wraps.

But it does suggest, however obliquely, a sense of divine destiny and universal morality. While we can see how racism, both covert and overt, took root in Johannesburg when the aliens began to outlive their welcome, it does not excuse it. And that—even in a film as hard and horror-filled as this—is saying something.

6. Moon (2009)

Duncan Zowie Haywood Jones is an English film director, film producer, and screenwriter (and, yes, tired of being constantly identified as the son of singer David Bowie). In addition to Moon, Jones directed the box office hit, Source Code (2011). His has been slated to direct the upcoming 2016 film adaptation of Warcraft.

The story in Moon is ostensibly about an astronaut who starts deteriorating mentally as his three-year solo stint on a lunar mining site is nearing an end. That being said, the movie is less about space than a drama whose central problem is what a single human identity might entail in a world where both cloning and highly exploitative impersonal labor practices have become commonplace.

In that respect, the film is a throwback to an earlier breed of science fiction: the techno-skeptical, isolated-in-space psychodrama. This type of film succeeded for a time after Stanley Kubrick demonstrated its possibilities in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Think Silent Running (1971), with Bruce Dern and his droids tending what’s left of the earth’s plant life in pressurized geodesic domes out near the rings of Saturn.

Or Solaris (Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1972 Soviet original, not Steven Soderbergh’s pallid Hollywood remake), with a distraught space-station crew experiencing hallucinatory episodes, and slowly realizing that they’re being caused by the planet they’re orbiting. This type of pensive sci-fi became eclipsed a few years later when Star Wars ushered in a cowboys-in-space era, and Alien brought back the monsters. Danny Boyle’s Sunshine (2007) had a save-the-planet ethos and aesthetically pleasing art direction – but even that devolved into a battle with a monster.

The film opens with an ad for Lunar Industries, a massive corporation that’s mining the moon to extract Helium 3, a precious gas that apparently offers a limitless source of clean energy for Earth. Then we meet the corporation’s only lunar employee, Sam Bell (Rockwell). He’s in the final weeks of his three-year contract, desperately lonely. He aches to go home to a wife and young daughter he can talk to only via videotaped messages.

Sam is aided in his lunar activities by a Hal-inspired, emoticon-faced, robot named Gerty (voiced by Kevin Spacey – more of a distraction because of the constant image of Spacey coming to one’s mind – unlike the comparatively much less well-known Douglas Rain as the voice of Hal). Gerty’s not around when Sam, driving out to retrieve a tank of Helium 3, has a meltdown and crashes into a huge mining machine. Waking up from the crash later in sick bay, Sam appears to be suffering from amnesia. He looks fitter than before the crash, though, and he’s being monitored far more closely by Gerty.

The film’s evocation of loneliness and the vast, silent reaches of outer space, is remarkably conveyed by Rockwell, as he holds the screen for two hours all by himself, ever stumbling while illuminating a fractured personality that is both at war with itself and its own best friend. The actor proves capable of embodying all sorts of contradictory impulses as his character becomes tragically self-aware.

The film’s ideas are interesting, but don’t feel entirely worked out, and Rockwell’s intriguingly strange performance (or performances) is left suspended, without the context that would give Sam’s plight its full emotional and philosophical impact. The smallness of this movie is decidedly a virtue, but also, in the end, something of a limitation.

Indeed, the one flaw in the film is that Jones wants to say more in the film that the remaining ninety minutes gives him (taking the first hour to develop the initial plot). The film attempts to comment on space travel for corporate gain, unfettered capitalism’s effect on workers, memory and the human mind, the consciousness of technology and, of course, human cloning. The film addresses each one well, but only far too briefly, with important plot points revealed in the blink of an eye.