5. Martha Marcy May Marlene (2011)

Martha, is one of several films put out by Borderline Films, a production company created in 2003 by three young Tisch film school alums, including Martha director, Sean Durkin. Durkin, and his Borderline cohorts Josh Mond and Antonio Campos have written, produced and directed films that discuss unorthodox issues facing unorthodox millennial youth. Rotating the roles of writer, director and producer, the three filmmakers have earned acclaim around the world for their stylized and original films. In addition to Martha, the group has produced Afterschool, Simon Killer and James White, each garnering various types of awards.

Martha premiered at the 2011 Sundance Film Festival, where Sean Durkin won the Best Director prize. The film was nominated for three Gotham Awards – Sean Durkin for Breakthrough Director, Elizabeth Olsen for Breakthrough Performance and Best Ensemble – and four Independent Spirit Awards: Best First Feature, Elizabeth Olsen for Best Female Lead, John Hawkes for Best Supporting Male and Josh Mond for the Producers Award. The film also received the Los Angeles Film Critics Association’s New Generation Award, shared by Sean Durkin, Antonio Campos, Josh Mond and Elizabeth Olsen.

Martha stars Elizabeth Olsen as Martha, a recent escapee of an abusive Catskill Mountains cult. Shortly after fleeing the group and their enigmatic leader (played by John Hawkes), she moves in with her semi-estranged sister and her sister’s husband in an attempt to assimilate back into society. In the end, Martha must overcome her psychological damage and return to normal life before her paranoia destroys the lives of everyone around her.

Durkin was so interested in the subject he made a short film, Mary Last Seen, before embarking on Martha. Indeed, he conducted a great deal of research about cults, including an interview with a personal friend who had once been involved in such a group, providing insight into the character that would be “Marcy May”.

Mary Last Seen stars Brady Corbet, who plays cult recruiter Watts in both the short and feature films. The short (a mere 15 minutes) shows how young women are recruited and brought to the cult’s farm house. The short is not a prequel or sequel, but exists as its own story within the world of Martha. That being said, it is worthwhile to see Martha before seeing the short. There is something particularly haunting about seeing someone’s beginnings in a cult after seeing someone else’s devastating ending.

Of course it is easy to claim as a shortcoming the fact that the behaviors exhibited are portrayed but not explained or ever resolved by Martha. The deep psychological trauma suffered by Martha is somewhat glossed over so that the audience does not receive a full understanding of the damage such cults can render to especially young minds. However, the film is not a psychology seminar for advanced students, and it remains successful for several reasons.

Durkin avoids stereotyping the cult as a pseudo-religious, kool-aid drinking caricature, instead portraying something more naturalistic and subtle. Organizations like the one featured in the film appeal to a need for community and belonging that many people crave. It is easy for those of us on the outside to deride groups like those headed by David Koresh or James Jones. Groups like the one Martha joined are far more horrifying precisely because of their apparent benignity; there is always something good at the beginning that is being offered, like love, community and acceptance – features often missing from the lives of today’s youth.

The slow, sometimes imperceptible, process of stripping of individual identity is well illustrated in the film. The cults leader, a guy called Patrick – chillingly performed by John Hawkes – renames the group’s devotees as a way of establishing psychological ownership by stripping each new recruit of their own identity: Martha’s new name was “Marcy May”. To add further layers to the process of de-identification, all the women in the group are given the name “Marlene” as a name to provide whenever they answer the telephone.

Flashbacks cleverly and indirectly disclose the repeat patterns of abuse and dysfunction that have damaged Martha’s mind. Such flashbacks are also used to evoke Martha’s inability to ground herself, even after leaving the group, and, indeed, to impress upon the audience

She is terrified and paranoid about being tracked down, perhaps with reason. Having tried one night to call one of her friends at the cult’s remote farmhouse HQ from Lucy’s house phone, she realizes too late that this has enabled the “callback” option, and perhaps allowed the cult to find her. The question of why she was able to escape so easily in the first place leaves a queasy slither of fear: have they, in fact, allowed her to escape? The film acted and directed like a sensitive drama, rather than a scary movie, and is all the scarier for it.

4. Beasts of the Southern Wild (2012)

Benh Zeitlin’s acclaimed first feature film, Beasts of the Southern Wild, tells the story of Hushpuppy, a six-year-old girl who lives with her father (Dwight Henry) in neighboring shacks in a place called the Bathtub, a swampy scrap of territory separated by a levee from a world of industry, consumerism and other forms of modern ugliness. The residents of the Bathtub spend their days fishing, scavenging and drinking, raising their kids to be self-sufficient and to believe in a folk religion featuring giant, ancient creatures called aurochs.

The Bathtub is offshore from New Orleans, isolated by levees, existing self-contained on its own terms. The distant profiles of drilling rigs and oil refineries might as well be mysterious prehistoric artifacts.

A fearsome storm is said to be on the way, but existence here is already post-apocalyptic, with the people cobbling together discarded items of civilization like the truck bed and oil drums that have been made into a boat. Their ramshackle houses perch uneasily on bits of high ground, and some are rebuilding them into arks that they hope will float through the flood.

Zeitlin, shooting on 16-millimeter film rather than in a digital format, and aided by his ingenious cinematographer, Ben Richardson, finds rugged, ragged beauty in nearly every shot.

Screenwriter Lucy Alibar originally wrote Beasts of the Southern Wild as a play called Juicy and Delicious, which was about an 11-year-old white boy and his father in southern Georgia, where she grew up. In adapting it to a 6-year-old black girl in the Louisiana swamps, Queens-bred director Benh Zeitlin turns it into a maudlin exercise in cultural tourism.

Juicy has been described as “a boy who feels like the whole world is collapsing as his father is dying,” and if that’s true, Zeitlin gets it somewhat backwards, setting up the collapsing world before the dying father, so that Hushpuppy’s dad getting sick feels like a symptom of the place instead of the cause for it, and a cliché symptom at that, of a place Zeitlin doesn’t seem too familiar with beyond the usual stereotypes in the first place.

Beasts is beautiful and the filmmakers are young, and may still have some great work in them yet, and many have described the film as “poetic.” But the film has a lot of that kind of poetry that’s not the work of someone employing a non-linear form to more closely illustrate their thought process as they grope towards meaning, it’s more like someone using poetry to obfuscate a story that wouldn’t work as prose, because there just isn’t much there.

3. The Babadook (2014)

This film was directed by the Australian actress and writer, Jennifer Kent. In 2005, Kent directed her short film Monster, which was screened at over fifty festivals around the world. In 2014 she adapted her short into a feature-length film The Babadook starring Essie Davis whom Kent had known since the two were at drama school.

The film tracks a widow (played by Essie Davis) and her descent into madness, in order to protect and bond with her son (Noah Wiseman). Davis plays Amelia, an Australian nursing home attendant who is reaching the end of her rope. She is haunted by the memory of her husband, who died in an accident on their way to the hospital to deliver Noah. The story begins years later. Amelia is constantly stressed out and exhausted. Most of her time is spent looking after Noah, a loving and imaginative but incredibly difficult child.

Amelia skims through clips of silent George Melies shorts late at night on her living room TV. Melies is a filmmaker who believed filmmakers are like magicians performing a grand illusion to audiences using cinematic tools. Magic is a of course a major theme in The Babadook, and indeed the whole film feels like a magic trick.

At first, Kent tricks us into thinking we’re about to watch a film about a problematic disturbed child who has access to another demonic dimension, but as soon as the Babadook creeps into their home, we begin to suspect that the problem isn’t with the child, but rather the mom.

The deeply disturbing demonic figure known as the Babadook erupts into their lives around the anniversary of her husband’s death, which coincides with her son’s birthday. The reading of an old children’s pop-up book titled “Mister Babadook” is what essentially unleashes hell upon them. The book is brilliantly designed with disturbing illustrations clearly influenced by German Expressionism. In fact, the creature resembles a character one would see in “Nosfertu” or “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari”.

So many horror movies, especially ones about poltergeists or possessions, try to tie in their central supernatural phenomena with some aspect of real life. These attempts at metaphor usually fall flat simply because the comparisons can be so ridiculous.

Take 2012’s The Possession, in which a Jewish demon’s grip on a young girl was supposed to be symbolic of how a child can act out when their parents divorce. That kind of problem isn’t solved by having Matisyahu chant Hebrew, however. We like to talk up horror as being effective because of how it can evoke the true dangers in life, but placing our normal anxieties alongside ghosts doesn’t automatically generate catharsis.

The malevolent Babadook is basically a physicalized form of the mother’s trauma, which centers not only on her husband’s death, but the additional grief created by the juxtaposition of the love for her son and the horrible memory that his birth – and continued existence – forever recalls. One could thus say that the Babadook embodies the destructive power of grief.

Throughout the film, we see the mother insist nobody bring up her husband’s name. She lives in constant denial. Amelia has repressed grief for years, refusing to surrender to it. Here lies the mastery of Kent’s film; it is frightfully clever because not only is it based on something very real, it is feels unusually beautiful and even therapeutic, if not cathartic.

2. Nightcrawler (2014)

Nightcrawler is a crime thriller film written and directed by Dan Gilroy. The film stars Jake Gyllenhaal as a former thief who starts shooting footage of accidents and crimes in Los Angeles, selling the content to local news channels as a stringer. It features Rene Russo, Riz Ahmed, and Bill Paxton.

In Nightcrawler, Gilroy ostensibly demonstrates the depth to which journalism can sink in modern society. “If it bleeds, it leads”. Gilroy was nominated for Best Original Screenplay for the film, not surprising given his authorship with his brother Tony of the screenplay for The Bourne Legacy.

That tabloid journalism rewards the shameless is certainly nothing new, but Nightcrawler is not interested in stoking our outrage over what we already know. The film using TV news as a means to an end – to show how a man who presents as “normal,” even “likable” and “motivated” and “capable,” can be evil, and seduce us into being evil as well. More deeply, Gilroy uses the the media’s fascination with atrocity as the canvas to convey an indictment on the effects of 21st century capitalism in the unchecked hands of corporate sociopaths with unbridled ambition.

This indictment is personified by Jake Gyllenhaal’s wonderful, almost zombie-like, performance as Lou, an unabashedly amoral street robber turned video stringer. After what appears to be yet another failure to sell stolen goods (capital) to a buyer (the market), Lou witnesses a camera crew filing an accident that has just occurred. Not at all phased by the horror of what has just occurred, nor emitting any sympathy for the accident victim, Lou is instead creepily fascinated by the simplicity of the crew’s “business model”.

So, Lou buys himself a cheap camcorder, plus a radio for listening in to police radio traffic, and gets to work. The idea that such work is invasive, legally questionable, and morally foul never troubles him. In fact, it never occurs to him. Thus unfettered, he barges in where others fear to tread, and soon, armed with close-ups of a carjacking victim expiring from a gunshot wound, he has his first scoop.

Lou’s inspirational aphorisms are chillingly funny once one realizes they are devoid of generosity and decency, and that he sees other people only as possessions, allies or obstructions: “I run a successful TV news business,” he says to Rick (Riz Ahmed), a quaking soul whom he hires as an assistant (“It’s an internship”), and later anoints as executive vice-president, amid plans to “expand to the next level.” Gyllenhaal wipes every fleck of irony from his voice as he makes these announcements, and one can see why. To him, feeding on carrion is not a sickness, or an outrage; it is just corporate practice.

Lou abuses the “working class” to further his fledgling news “company”, even to the point of setting up his recalcitrant protégé to get shot by a per they have been following, not only for the blood-drenched money-shot, but for Lou to rid himself of the erstwhile asset now turned traitor (liability) to the company – (i.e., management’s reaction to the working class demonstration of an individual identity separate from that of the corporate body and self-determination to rectify the institutional inequity [and iniquity]).

Gyllenhaal masterfully evokes the dead-eyed, heartless criminals who run and ruin our country with impunity from leather-bound offices on Wall Street, impervious to scrutiny and immune to the offices of justice. Lou’s skin is skull-pale, drawn as tight as a drum and starved of light, as he sucks up every flicker of neon and moonshine. Lou behaves like he is impervious to consequences, and a chilling take from the film is that, like the world of Big Business he embodies, he is right.

A still more chilling take, however, is spelled out in that final scene. Lou, and people like him, not only win, but win with society’s support an encouragement. By tuning into local news and falling prey to click bait, we are all complicit in the over-sensationalization of our media and the stripping away of any sense of humanity.

Similarly, as we wake up each day programmed to dream of becoming the next Mark Zuckerberg or Uber’s Travis Kalanick, we turn blind eyes to the catastrophic collateral damage created by the inequity such corporate zombies perpetuate.

1. EX Machina (2015)

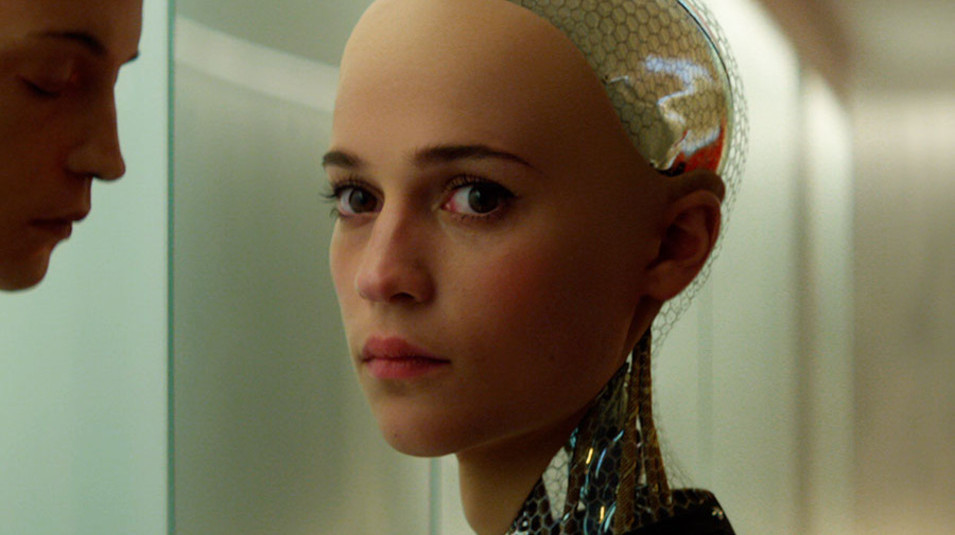

Ex Machina is a 2015 British science fiction/psychological thriller film written and directed by Alex Garland in his directing debut. It stars Domhnall Gleeson, Alicia Vikander, Sonoya Mizuno and Oscar Isaac. Ex Machina tells the story of programmer Caleb Smith (Gleeson) who is invited by his employer, the eccentric billionaire Nathan Bateman (Isaac), to administer the Turing test to an android with artificial intelligence (Vikander).

With a budget of $15 million, the film grossed over $36 million worldwide and received critical acclaim for its writing and acting. The National Board of Review recognized it as one of the ten best independent films of the year, and Vikander received a Golden Globe Award nomination for Best Supporting Actress in a Motion Picture.

In the movie, Garland takes a base question—what is consciousness?—and wanders down every theoretical avenue. Isaac’s tech-bro character traces a line from Google Search to sentient A.I., Gleeson’s office drone imagines inventors as God replacements, and Vikander, as the graceful robot Ava, challenges the human identity with her mere existence.

The question of whether it is possible for machines to think has a long history, which is firmly entrenched in the distinction between dualist and materialist views of the mind. According to dualism, the mind is non-physical (or, at the very least, has non-physical properties) and, therefore, cannot be explained in purely physical terms.

According to materialism, the mind can be explained physically, which leaves open the possibility of minds that are produced artificially. Stories about artificial intelligence are a frequent science fiction topic, from Czech writer Karel Capek’s 1920 play R.U.R. (which coined the term “robot”) to Kubrick’s (then Spielberg’s) A.I. and Spike Jonze’s invisible Her.

Ex Machina is deceptively simple, essentially just three characters: the aggressive, beer-swilling Nathan; the innocent, inquisitive Caleb; the quick study with the ballerina’s gait and the blinking lights in her abdomen, Ava. The dynamics among the three shift and sway, as Caleb is first allied with his mentor, Nathan, and then won over by Ava.

What follows is a smart and sophisticated psychological thriller in which every conversation is laced with tension. As the sessions progress, proceedings take a dark turn as all three sides of the bizarre love triangle use lies and manipulation as a means to achieve the very different ends they are after; the challenging sci-fi slowly morphing into horror.

Oscar Isaac’s character is an enigma from the beginning, and Isaac achieves the impressive feat of making him both likeable and terrifying.

The Swedish-born Alicia Vikander puts her training as a ballerina to good use through both Ava’s stillness and the manner in which she moves, and she’s aided and abetted by some remarkable-yet-subtle visual effects work. But it’s the humanity Vikander brings to the character that ensures Ex Machina works, making it easy for the audience to forget that this is a human playing a machine, and instead believe that Ava is a living, breathing, thinking being entirely capable of passing any test put in front of her.

But the real star of the show is Alex Garland. The son of a psychoanalyst and a political cartoonist, Garland started his career as novelist before penning the scripts for provocative science fiction movies like 28 Days Later, Sunshine, Never Let Me Go, and Dredd. With Ex Machina, Garland upgrades to the role of director, enabling him to drill sci-minded queries and hypotheticals into his audiences’ brains with even more force. Garland spent ten years researching the film.

Among the books key to his inspiration were Machine Language for Beginners by Richard Mansfield, The Emperor’s New Mind by Roger Penrose, and Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations. Two films also served as inspiration: 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Altered States.

It may be a cautionary tale that combines smart sci-fi with unsettling horror, but the most disturbing aspect of Ex Machina is the plausibility of the storyline, with it easy to imagine events like this playing out in the real world. Anchored by three dazzling central performances, it’s a stunning directorial debut from Alex Garland that’s essential viewing for anyone with even a passing interest in where technology is taking us.

Honorable Mentions:

The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada (2005 – Tommy Lee Jones)

Fateless (2005 – Lajos Koltai)

A Single Man (2009 – Tom Ford)

The Whistleblower (2010 – Larysa Kondracki)

Waar (2013 – Hassan Rana)

The Day I Became a Woman (2000 – Marzieh Meshkini)

Poetical Refugee – (2000 – Abdellatif Kechiche)

Monster (2002 – Vadim Perelman)

Maria Full of Grace (2004 – Joshua Marston)

In the Land of Blood and Honey (2011 – Angelina Jolie)