8. Into Great Silence (Philip Groning, 2005)

Philip Groning’s non-narrative documentary follows the day to day lives of the Carthusian monks of the Grande Chartreuse, an ascetic monastery high up in the French alps. Having proposed his idea in 1984, Groning was finally given permission to film and live at the monastery 16 years later; it took him another two years to finish editing. Groning’s film illustrates people’s ability to endure severe austerity by embracing faith.

Into Great Silence documents the strict ascetic lives of the Carthusian monks. Located in the Chartreuse Mountains and closed to visitors, The Grande Chartreuse is secluded from the outside world. The Carthusian’s believe that by giving up everything and embracing their faith, they become closer to God, who acknowledges their sacrifice. The monks adopt a strict vow of silence as they go about their rigid routine of prayer, work, and study.

Into Great Silence illuminates the transcending powers of faith. Groening’s captures the severe conditions in which the monks live. Despite the fact that many of the monks are elderly, they perform labor intensive work in harsh conditions. The monks solemnly shovel snow and chop wood, while wearing nothing more than a cloak.

During the only interview of the film, a monk proclaims that happiness involves being close to God, and that those that do not have faith do not have a reason to live. Groening’s documentary illustrates that when people believe in something beyond themselves, they can endure severe hardship.

7. Baraka (Ron Fricke, 1992)

A follow up to Godfrey Reggio’s experimental film Koyaanisqatsi, for which he was the cinematographer, Ron Fricke’s non-narrative documentary captures the awe and wonder in life. In Arabic, the word “Baraka” refers to a kind of spiritual force which flows from god and permeates throughout the world. With a focus on documenting astonishing natural events, cultural performances, and the fruits of human creativity, Baraka evokes a sense of divine inspiration

Baraka honors man’s creative production, exhibiting visionary man-made structures such as the Ryoan Buddhist temple in Kyoto Japan, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, and the Terracotta Army in Shaanxi China.

The camera captures awe inspiring imagery of natural events, from the raging water falls of Iguazu falls in Argentina, to the billowing and smoldering of an active volcano. Perhaps most impressive is Baraka’s aptness in examining powerful cultural ceremony’s without being invasive. The viewer is given the opportunity to candidly observe cultural expression that he may not otherwise have access to.

Capturing the powerful sense of transcendence that arises from the experience of beauty, Baraka celebrates the flow of divine inspiration from nature, to man, to his creations.

6. Tree of Life (Terrence Malick, 2011)

Winner of the 2011 Palm d’Or, Tree of Life chronicles the existence of the universe while exploring the meaning of life.

The film opens with the image of the cosmos, empty and totally void, except for a wavering flame. Mrs. O’Brien (Jessica Chastain) suggests that there are two ways through life: the way of nature, and the way of grace. One must choose which path to follow. She explains that grace does not try to please itself, but accepts things as they are, whereas nature seeks to please itself, and to have things its own way. Mr. and Mrs. O’Brien are notified that their youngest son has died.

Their family is thrown into turmoil. Mr. O’Brien (Brad Pitt) expresses his remorse for being so hard on his son. The film then begins to follow Mr. and Mrs. O’Brien’s eldest son Jack (Sean Penn), as he recalls his childhood a, torn between following the path of nature (personified by his authoritarian father) and the path of grace (personified by his tolerant mother). Unable to reconcile the opposing perspectives on life that have been passed onto him, Jack struggles to cope with his younger brother’s death.

Tree of Life is a meditation on the meaning of life as experienced through the eyes a young boy. Malick’s documentary-like style of chronicling the universe suggests that the universe is void of any inherent purpose or meaning. The creation of the cosmos and the destruction of a planet are just a course of events that cannot be assigned any moral value. Malick proposes that how one views the universe, and how one lives, is a choice.

5. Koyaanisqatsi (Godfrey Reggio, 1982)

An experimental film consisting in real-time, slow motion, and time-lapse footage of natural and industrial landscapes across the United States, Koyaanisqatsi illustrates technologies prevalence across all facets of human existence.

Reggio uses striking imagery, coupled with a haunting soundtrack composed by Phillip Glass, to illuminate man’s relationship with technology. Reggio acknowledges the prominence man has been able to achieve through technological advancement, yet prophesizes tragic consequences as a result of man’s utter dependence on technology.

Koyaanisqatsi begins with an image of the Holy Ghost panel in the Great Gallery of Horseshoe Canyon. The primitive art work depicts a group of shapeless, featureless, beings (commonly referred to as the Holy Ghosts) surrounding a figure adorned with a crown. Set to a haunting score named after the title of the film, the audience is then shown spectacular slow motion footage of a rocket launch.

After hovering over America’s barren desert landscapes and sparkling oceans, the camera shifts its focus to the areas of land where nature and technology intersect. Pipelines are shown extending across vast deserts. Factories are revealed amidst sprawling landscapes.

The film then begins to take a more optimistic tone, focusing on the awe-inspiring ways technology has shaped modern society. The audience is shown footage of highways, city sky-scrapers, and stunning images of satellite photography which capture the expansive layout of industrialization.

This is followed by a more stirring version of the opening score, coupled with footage of people solemnly going about their daily lives in the city. The film then revisits the rocket launch, which is shown exploding after take-off, and concludes with another image from the Great Gallery.

In the Hopi language, Koyaanisqatsi translates to “A life out of balance,” a message that Reggio does not fail to convey in his film. Reggio’s choice of footage uniquely displays man’s illustrious, but doomed relationship with technology. Humanity has managed to incorporate technology into every aspect of human existence. Reggio’s alluring cinematic work of art, depicts man as having become dangerously dependent on the volatile forces of technology.

4. The Holy Mountain (Alejandro Jodorowsky, 1973)

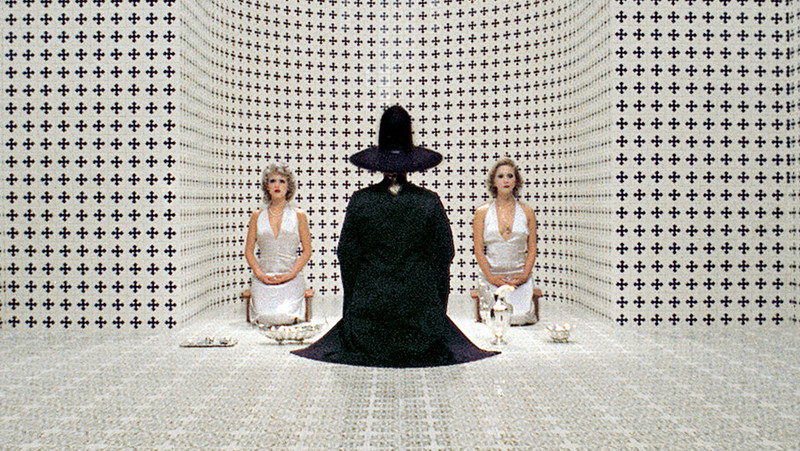

Jodorowsky’s psychedelic cult classic, The Holy Mountain, serves as a guide for attaining enlightenment. Jodorowsky challenges the audience to shed themselves from all beliefs and perceptions, and to follow him on a journey to acquire the secrets of the immortals.

The film begins with the ritualistic initiation of two women. They are stripped of all material things which signify culture, as they are being prepared for rebirth. The camera then focuses on an eye, before hovering over various symbols including a key. Jodorowsky is inviting the viewer on a journey to unlock the divine knowledge of the mind.

The film then cuts to a man (identified as the thief) covered in flies and lying in urine amongst empty bottles of liquor. He is approached by a handless, footless dwarf. The two travel to the city to make money from tourists. After employing various money making schemes, the thief observes a crowd of people gathered around a tower, where gold is being lowered by a hook in exchange for food. The thief climbs the tower hoping to find the source of the gold.

Upon entering the tower, the thief is met by an alchemist (played by Jordowosky). After a brief confrontation, the alchemist accepts the thief as an apprentice. The alchemist and the thief, along with a team of nine powerful men and women, embark on a journey to climb the holy mountain of Lotus Island, in order to conquer the secrets of the immortals.

The Holy Mountain takes its audience on a psychedelic journey toward enlightenment. The film uses surreal imagery, a powerful soundtrack, and evocative themes to create a transcendent experience. Jodorowsky alters his audience’s state of mind, and guides them through a spiritual exploration, culminating with a plea for his viewers to continue the journey in reality.

3. 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968)

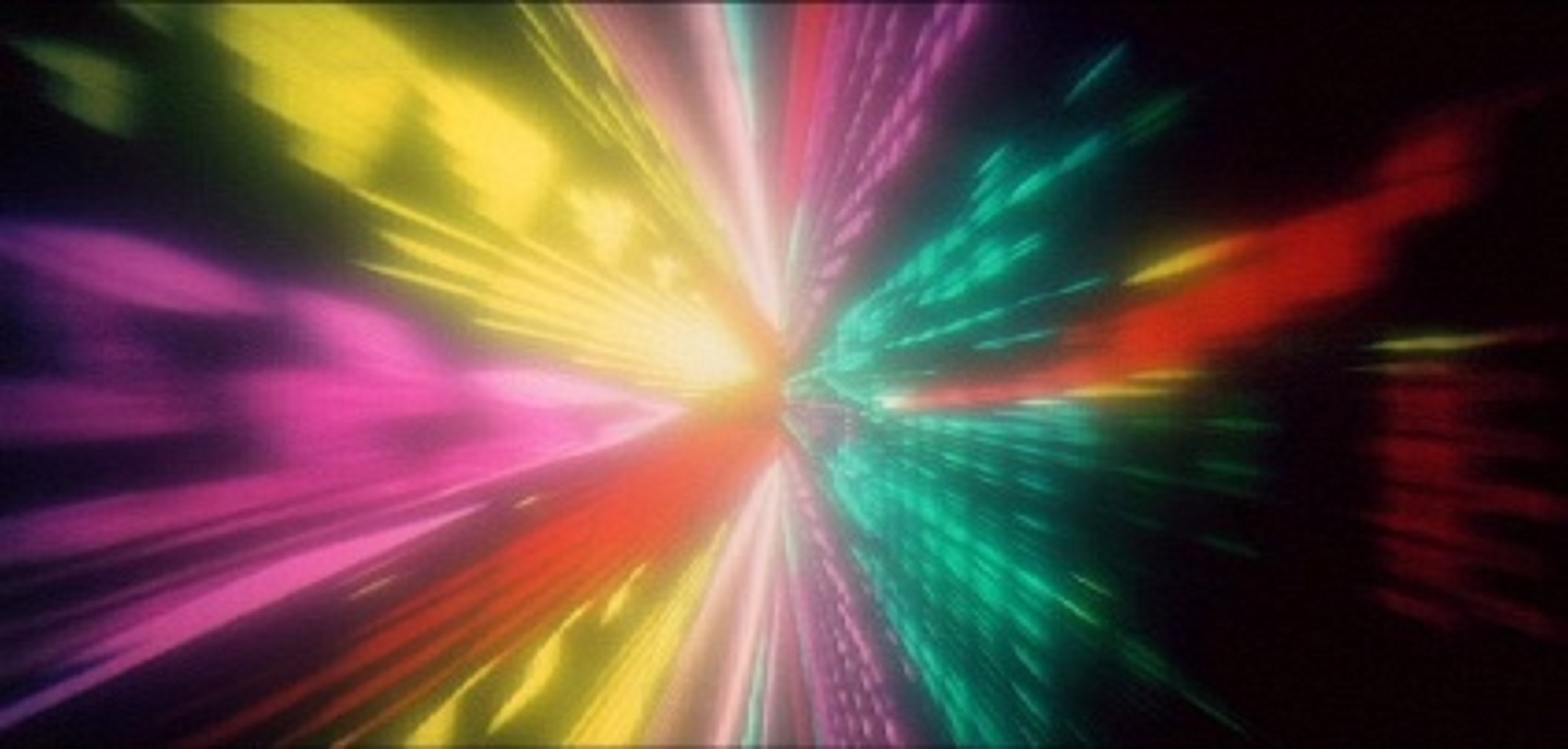

Widely regarded as one of the greatest films of all time, Stanley Kubrick’s sci-fi masterpiece depicts human evolution, from early hominids to modern humans, and beyond. 2001 recognizes that humans, like all known life-forms, represent a point in the evolutionary process, not an end. Acknowledging the crucial role technology has played in man’s evolution, 2001 suggests that man, with the aid of technology, will transcend himself.

The film begins on earth, before humankind dominated the planet. A group of hominids are shown drinking from a water hole, before they are driven away by a rival tribe. One day a mysterious black monolith appears. Astonished, the hominids surround the monolith screaming and probing it with wonder. Shortly thereafter, one of the hominids is inspired to use a large bone as a club to kill and eat meat. The hominids then use clubs to kill the leader of their rivals.

The film then fast forwards millions of years. A group of scientists have discovered a mysterious black monolith buried on the moon. Eighteen months later, a U.S. spacecraft, Discovery One, is bound for Jupiter.

Discovery One is manned by a crew of five (three of which are in cryogenic hibernation) and controlled by an A.I. named Hal. After making an error, the crew becomes concerned with Hal. Fearing he will be disconnected, Hal begins to take drastic measures to preserve his life. It is soon revealed that unbeknownst to the crew, the primary mission of Discovery One is to investigate the finding of another black monolith orbiting Jupiter.

Stanley Kubrick depicts technology as an intrinsic component to human evolution. Inspired by the monolith, the hominids discover the use of large bones as tools for acquiring food. This represents the first interaction between man and technology.

The hominids then learn that they can use the bones for other purposes, such as weapons, illustrating the dynamic nature of man’s interaction with technology. In the film, man encounters the mysterious monolith again, in space, accelerating man’s potential. 2001 acknowledges that technology has played a crucial role in shaping early hominids into modern man, and that technology will continue shape man into something far beyond himself.

2. The Seventh Seal (Ingmar Bergman, 1957)

One of world cinemas most iconic films, The Seventh Seal is a lamentation on the inadequacy of faith to justify tragedy. Ingmar Bergman provokes the audience to confront what he refers to as “the silence of God.”

A weary knight, Antonius Block (Max Von Sydow), and his squire, Jons (Gunnar Bjornstrand), return from battle in the Crusades only to find their homeland Sweden ravaged by the plague. While resting at a beach, Antonius is confronted by Death, which has taken the form of a pale monk dressed in black.

Antonius expresses that he is not ready to die, and challenges death to a game of chess. Antonius is allowed to live for as long as he can remain in the game. At a church, the knight enters the confessional, where he admits that he has lost his faith. He questions God’s absence in the face of tragedy. He wants God to speak to him, to reveal himself to him in some way. Antonius then proclaims that his life has been nothing, and that before he dies he wishes to perform one meaningful deed.

The Seventh Seal questions Gods absence. As a crusader, Antonius fought and killed in the name of God, only to return home to a plague stricken land .He has seen and experienced a great deal of suffering, and has failed to see any sign of Gods intervention. Bergman provokes the audience to confront a question: if there is a God, why does he not reveal himself?

1. Solaris (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1972)

An adaptation of the novel by the same name written by Stanislaw Lem, Solaris explores the concept of knowledge, emphasizing humanity’s inability to understand or communicate with other forms of life. By confronting mankind’s existential limitations, the film calls into question man’s place in the cosmos.

Kris Kelvin (Donatas Banionis) is a psychologist tasked with the mission to travel to the Solaris Station (a research station hovering over the ocean planet named Solaris) in order to determine whether research on the ocean planet should be abandoned. Thus far, research on Solaris has suggested the fantastic hypothesis that the planet has a distinctive brain and may be capable of thought.

Due to disturbing phenomenon experienced by those on board the research station, and the unintelligible data obtained during the planet’s surveillance, only three researchers remain at the station: Snaut (Juri Jarvet), Sartoirious (Anatoly Solonitsyn), and Dr. Gribaryan (Sos Sargsyan). Kris arrives only to find the space station grossly neglected and that Dr. Gribaryan has committed suicide.

As the film progresses, it becomes apparent that Solaris is studying the research crew. Kris struggles desperately to understand what (if anything) Solaris is trying to communicate. Confronted with the futility of trying to establish communication with Solaris, the crew struggles to hold onto their notions regarding the purpose of man’s existence.

Solaris challenges the concept of man as a being with limitless potential, thus calling man’s purpose into question. The crew cannot communicate with Solaris because Solaris is a distinctive being, fundamentally different from humans. Without communication there is no understanding. If we cannot understand the cosmos, then why should we explore it? If man is not meant to explore, then what is his purpose?

Author Bio: Jonathan holds a B.A. in Philosophy from UCLA, and is currently pursuing a career in Journalism. On his spare time, Jonathan enjoys writing, kickboxing, and creating music.Check out his music on bandcamp: https://szamanka.bandcamp.com/.