Not all great films end neatly. Many directors choose to end their films abruptly or with unanswered questions, forcing audiences to watch, rewatch, and obsess over them until they can make sense of it for themselves – and sometimes even then the film is still inscrutable.

For a filmmaker to not reveal all their cards to the viewers is a bold move and, naturally, it doesn’t always work as planned (see: David Fincher’s tear-your-hair-out frustrating thriller The Game), but when it does work it can lead to truly stunning, mysterious films that deserve all the attention and acclaim they get.

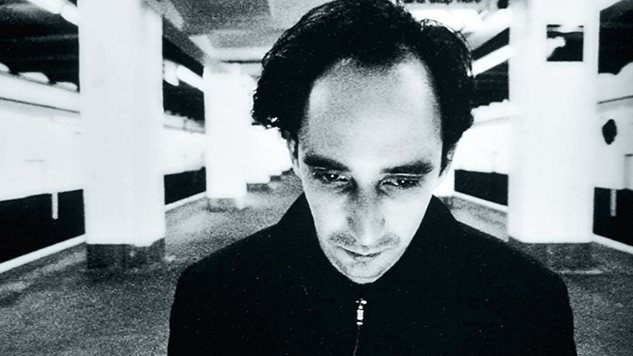

15. Pi (1998, Darren Aronofsky)

Those who only know Darren Aronofsky from his writing/directing work on bible-reenactment-sans-melanin Noah might have gotten the wrong impression of the director’s intense style.

Although his name has become big enough for him to be offered whitewashed religious blockbusters, he got his start with the brooding low-budget thriller Pi, which cost a mere $68,000: 1/1800th of the budget for raging-garbage-fire-set-to-film Noah.

Pi is everything that movie isn’t: understated, intricate, and intelligent, it’s an independent film in the truest sense of the term. With a cast made up of primarily non-professional actors, Aronofosky crafts a detailed and compelling world within his film that draws the viewer in through clever filmmaking rather than expensive special effects.

The film revolves around Max Cohen’s gradual descent into paranoia and obsession while studying a bizarre number that may have divine implications. Cohen, a man who can perform complex math functions in his head without breaking a sweat, becomes embroiled in both a wall street conspiracy as well as a quest for the religious and spiritual implications of the mysterious 216-digit number he discovered.

Everything from Jewish kabbalah, sacred geometry, chaos theory, and the Japanese game of Go are discussed in depth, making for a dense but deeply fascinating thriller.

Aronofsky asks a lot of his audience by taking on such heady topics, but the payoff is astounding; it’s easily one of the smartest thrillers of the ‘90s as well as a brilliantly idiosyncratic debut for a director who would go on to make many similarly dark and intense films (and one very, very bad biblical epic).

14. Gozu (2003, Takashi Miike)

One of the strangest films in Takashi Miike’s already bizarre filmography, Gozu is nonsense for the sake of nonsense and it’s all the better for it.

It’s a disjointed rollercoaster ride of a movie, going from one comically surreal scene to another with little space to breathe in between. All this eccentricity is just barely tied together by a vague narrative about a yakuza hitman hired to kill his unstable mob boss in a small town that makes Twin Peaks seem normal.

It loosely connects to some Greek myths, with the title – meaning “cow head” in Japanese – referring to a minotaur that pops his head into the story in one of the most simultaneously hilarious and viscerally disturbing scenes of the movie.

That said, it’s hard to tell that there’s any rhyme or reason behind the outrageous images; it seems far more likely that Miike was just aiming to confuse and provoke with the strangest imagery possible, with little consideration of structure or organization.

As a whole the film is incoherent, crude, and possibly even pointless, but it’s also excessive in all the right ways. It’s a David Lynch movie if Lynch stopped caring and just threw all his ideas on paper without bothering to make sense of any of them. Takashi Miike’s best film this isn’t (see: 1999’s Audition), but in terms of joyful chaos and originality it’s hard to beat.

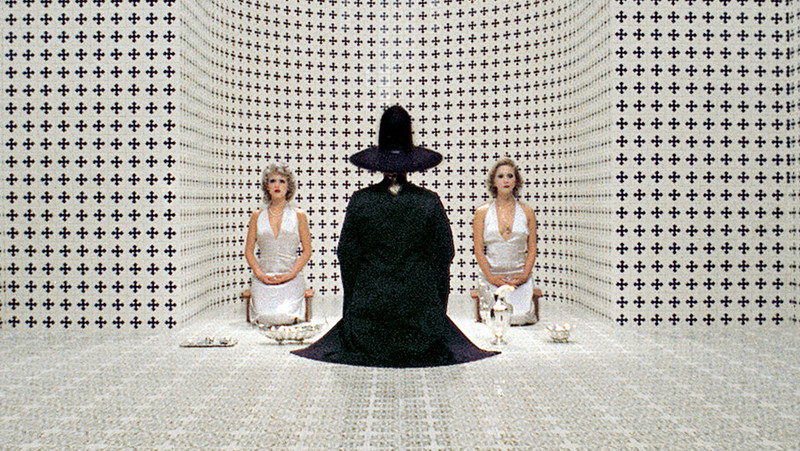

13. Zigeunerweisen (1980, Seijun Suzuki)

He’s best known in America for the jazzy yakuza B-thrillers he made in the ‘60s (Branded to Kill, Tokyo Drifter), but Seijun Suzuki’s more acclaimed work in his home-country of Japan is actually a late-career series of far more serious films: his Taishō trilogy, made up of Zigeunerweisen, Kagero-za, and Yumeji.

All three films are deeply surreal ghost stories reflecting on the Taishō era of Japanese history, a period in the 1910s and 1920s during which Western culture became assimilated into Japanese culture.

Zigeunerweisen, titled after a famous German violin composition of the same name, is the first entry in this trilogy as well as the most brilliantly idiosyncratic. Unlike Suzuki’s more playful early films, it’s got a deeply intellectual backbone and frequently refers to other art both directly and indirectly; among other things, Vertigo could be seen as a frame of reference, although the themes are communicated in wildly different ways.

The film follows two men, a German professor named Aochi and his former student turned vagabond named Nakasago, who cross paths after decades apart and fall in love with the same beautiful geisha. They decide Aochi will marry the geisha and Nakasago will go off to find his own wife, but when Aochi meets the Nakasago’s new wife six months later he discovers that their spouses are virtually indistinguishable.

Things only become stranger when they begin to hear whispering voices on Aochi’s recording of Zigeunerweisen and rumors of a very kinky affair start to swirl.

The plot is made up of a series of loosely connected events that drift into each other rather than one continuous story arc, which can make it a challenge to follow, but giving in to the film’s strange atmosphere is well worth it come the eerie, creepier-than-creepy finale.

12. Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010, Apichatpong Weerasethakul)

Apichatpong Weerasethakul – often referred to in the Western world as simply “Joe” – is the most important director working in Thailand today as well as one of the foremost auteurs of world cinema in general. His slow, dreamy style is inseparable from his homeland, which can make his work alienating to non-Thai audiences simply because a basic knowledge of Thai culture and history is essential to the understanding of his work.

His films can still entertain and enthrall despite this though, as can be seen in his greatest film yet, the Palme d’Or-winning drama Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives.

The basic narrative that ties the film together shouldn’t come as a surprise considering the title; Boonmee is a man on his death bed, spending his last few days of life with his family as he looks back and remembers the past lives he lived before he was reincarnated in his present body.

It’s clearly a Buddhist film, as many of Joe’s films are, as well as a uniquely Thai one; Boonmee is an analog of Thailand, as his past lives all evoke the history, myths, and spirituality of his country.

Understanding the meaning behind the surreal plot developments isn’t required to enjoy the film, however; it’s a stunning film that, regardless of the viewer’s prior knowledge, is hypnotic and overflowing with beauty and magic.

11. Berberian Sound Studio (2013, Peter Strickland)

While the golden age of the Italian horror sub-genre giallo surely left its imprint on the public consciousness – in particular by spawning the slasher film craze of the ‘80s – its legacy is harder to spot among more recent horror offerings. Berberian Sound Studio, a psychological thriller that flew under the radar of most horror fans, is one of the few recent films to wear that giallo influence on its sleeve.

It’s far from a throwback or rehash of classic Italian horror films like Suspiria or Blood and Black Lace though: any and all allusions to those older films happen off-screen in the film-within-a-film.

Timid British sound engineer Gilderoy (Toby Jones, in one of his most nuanced performances yet) is the sound engineer hired to work on the aforementioned fictional giallo film, The Equestrian Vortex. Gilderoy isn’t sure how or why he got hired for the grotesquely violent film, having only had previous experience with nature documentaries, but he accepts the part nonetheless.

He quickly regrets that decision as the day-to-day routine of recording screams and stabbed watermelons – sound effects for The Equestrian Vortex’s countless murder scenes – wears down on him; he becomes increasingly paranoid and slowly but surely his sanity wanes, leading to a spectacularly hallucinatory third act that unnerves on a primal level, to say the least.

The film is a slow-burner to be sure, but in taking its time it builds up an unbearable amount of dread that pays off in a big way. Like the giallo films to which it owes a stylistic debt, it’s not “BOO!” scary so much as it is profoundly unsettling and tense. Once the plot kicks into high gear, it doesn’t turn back; it’s a powder keg of terror that builds and builds until it reaches its unpredictable climax – then it takes it all a step further into uncanny territory.

The creepy but gorgeous soundtrack by legendary indie electronic band Broadcast – their last official release before lead singer Trish Keenan’s tragic death – only adds to the suffocating atmosphere, perfectly complementing the uneasy mood of the film.