10. Code Unknown (2000, Michael Haneke)

Austrian director Michael Haneke is one of the most underappreciated filmmakers working today, having crafted some of the most disturbing but intelligent and thoughtful films of the last 30 years. Code Unknown is not necessarily his best film – that honor belongs to Caché or Amour – but it’s without a doubt one of his most fascinating and unique works.

The film is made up of a series of unedited long-takes, each one focusing on a different character, that all intersect to form an overarching narrative related to immigrants and racism. Each segment cuts away abruptly after a few minutes, often mid-sentence, giving the audience a peek into the lives of each character but always leaving key details of their story ambiguous.

It’s a cinematic jigsaw puzzle, made up of numerous narrative fragments that the audience is left to piece together into a coherent whole on their own. To complicate things further, not all the segments seem to relate to the central narrative – that of a white teenager kicking off a chain reaction of tragedy after he publically humiliates a homeless Romanian woman.

It’s a frustrating film by design, but it’s frustrating because it’s real. As an audience we’re trained to expect neat and fair resolutions to the stories we see on screen, and Haneke explicitly denies us this satisfaction in order to a communicate a real-world truth that has only become more relevant since the film’s release: xenophobia and racism is deeply ingrained into Western society and nothing can change until we each confront our own personal complicity in the hatred and violence.

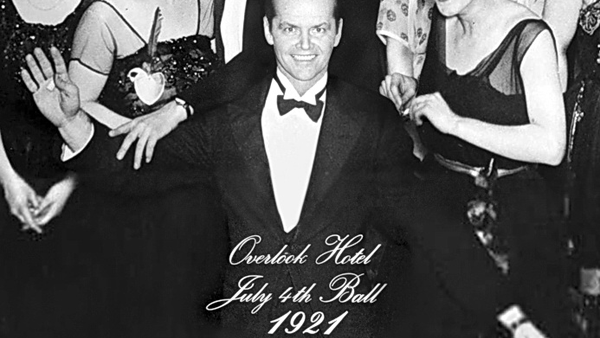

9. The Shining (1980, Stanley Kubrick)

Two Stanley Kubrick films on one list may seem a little excessive, but the man knew how to end on an ambiguous note. The Shining is one of the few horror films to trust its audience enough to ask dozens of questions and never answer any of them by the time the credits roll.

There have been countless fan theories about what it means, ranging from moon landing conspiracies to Native American genocide allegories to male fears of female sexuality – spoiler alert, that big ol’ bloody elevator is a vaginal symbol. A critically acclaimed documentary was even released a few years ago that served solely as a tool to collect and discuss the various interpretations behind the film.

Very few of the interpretations hold up upon close inspection – one particularly ridiculous one is that the film was meant to be watched forwards and backwards at the same time, with the two images overlaid – but the film is so mysterious and vague in its meaning that it’s fun to entertain the various theories.

The story of the Overlook Hotel and its ghostly inhabitants has remained in the cultural consciousness first and foremost because it’s flat-out terrifying, but also simply because it retains its mysteriousness to this day.

Few perfect interpretations exist, and it’s unlikely that any interpretative breakthroughs are going to be made this far down the line. For better or worse Kubrick designed it to be unexplainable, and because of that it will likely remain in the public eye indefinitely as a filmic enigma.

8. Eden and After (1970, Alain Robbe-Grillet)

Alain Robbe-Grillet’s claim to fame is his post-modern, wildly unconventional novels as part of the Nouveau Roman literary movement in the 1950s as well as his collaborations with French New Wave stalwart Alain Resnais, and he carries that sense of unbridled imagination over to his stint as a director.

Eden and After, his fourth film, is perhaps his most uninhibited and criminally underrated. Lying somewhere at the crossroads of an experimental film, a psychological thriller, and an S&M drama for people with too much self-respect to try E.L. James novels, it’s an anomaly that isn’t always easy to follow but is never less than gripping.

The loose narrative concerns a group of French college students who, after being drawn into a charismatic stranger’s bizarre mind-games and consuming the mysterious “fear powder” he offers them, fall into a psychosexual nightmare that leads them from a Parisian café (the “Eden” of the title) all the way to Tunisia (the “after”).

The film drifts from scene to scene on a sort of elliptical dream logic, never submitting to conventional linear storytelling or spelling out what it’s trying to say in simple terms. Instead we’re treated to a candy-colored cinematic puzzle on par with Grillet and Alain Resnais’ similarly mysterious yet far more widely recognized Last Year At Marienbad: bold, gorgeous, and unrepentantly surreal.

7. Persona (1966, Ingmar Bergman)

Persona’s status as the definitive foreign art film has surely led countless people to keep their distance in fear of pretension and boredom. Those fears couldn’t be less grounded in reality, however; Persona is definitely a film student’s film, but it’s also incredibly tense, creepy, and eminently enjoyable.

Ingmar Bergman has acquired a reputation as a dry, academic filmmaker amongst some movie fans – which, in a sense, is fair considering that most of his output is about the nonexistence of God –, but his output, and Persona in particular, is often marked by emotional fireworks, tense interpersonal dynamics, and striking visual symbolism, making it anything but a bore.

The film concerns two women: a stage actress who suddenly stopped speaking mid-performance and the nurse who is hired to take care of her until she regains her voice, played by Bergman muses Liv Ullman and Bibi Andersson respectively. Their interactions become increasingly fraught as their identities begin to blur together and merge, throwing the doctor/patient relationship into chaos.

What begins as a fairly simple drama – although a bizarre framing device at the beginning makes clear early on that it’s far from an ordinary movie – escalates rapidly into an impenetrable and nightmarish psychodrama meltdown where traditional narrative techniques are thrown out the window and nothing is off-limits.

6. The Holy Mountain (1973, Alejandro Jodorowsky)

There really is nothing else out there like The Holy Mountain. Alejandro Jodorowsky, the man who literally invented the concept of midnight movies, hit his peak with this bizarre mystical odyssey by turns profound and hilarious.

Featuring one indelible image after another – ranging from the Spanish conquest of Mexico reenacted by frogs and iguanas to a gun disguised as a menorah –, the film is a cinematic freak show loosely tied together by a fittingly convoluted narrative.

Jodorowsky himself plays the alchemist at the center of the story who guides a Christ-like thief and seven other people who each represent a different planet of our solar system on a spiritual quest: they must all travel to Lotus Island to learn the secret of immortality from the nine masters who live atop the holy mountain.

It’s all very typical of Jodorowsky’s modus operandi: filled with tarot symbolism, spectacularly surreal imagery, little to no narrative, and an absurd sense of humor beneath it all. Even among Jodorowsky’s work, however, The Holy Mountain is a treasure; it’s the Citizen Kane of cult filmmaking, a dazzling, messy marvel that towers far above every film that dared to follow in its footsteps.