5. Solaris (1972, Andrei Tarkovsky)

Tarkovsky’s lone foray into pure genre filmmaking was marketed as the Soviet response to Kubrick’s 2001, but that doesn’t do either film justice.

Yes, they’re both science-fiction movies that take place in space, approach three hours, and have deeply philosophical undertones, but otherwise they are radically different films; to paraphrase Roger Ebert, 2001 looks outward at man’s past, present, and future while Solaris looks inward at what makes us human.

Telling a very personal story on a very large canvas, Solaris explores a scientist’s love, loss, and grief when he is sent to a space station orbiting Solaris, a planet that can create physical manifestations of humans’ memories.

The planet creates a double of the scientist’s former lover aboard the ship, causing a whole lot of existential crises for both parties as they’re left unsure of whether or not to continue their passionate love affair despite one of them technically not existing.

Tarkovsky explores this narrative from a variety of thoughtful angles, incorporating philosophy and a number of intertextual references to other works of art to get its themes across effectively; in other words this is a dense movie with a lot on its mind, far more than most other sci-fi movies, and because of that it can try the patience at times.

Sticking with it yields rewards though, as Solaris stands as one of the most intelligent, uncompromised, and deeply moving films of Tarkovsky’s acclaimed career.

4. Repo Man (1984, Alex Cox)

How does one describe Alex Cox’s offbeat cult masterpiece Repo Man? Well, for starters, it’s Emilio Estevez’s career peak; forget The Breakfast Club, his role as punk-turned-grocery-clerk-turned-repo-man Otto is indisputably his best and most iconic.

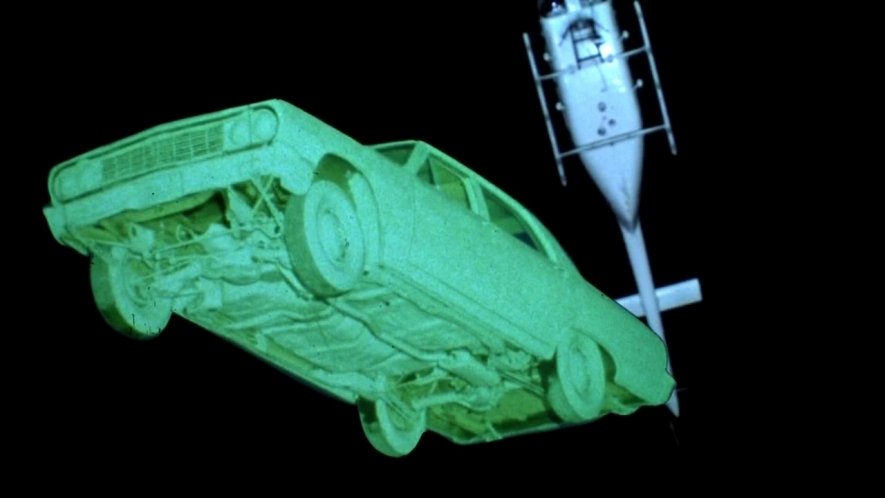

Harry Dean Stanton is equally flawless as the repo man who lures Otto into his unique line of work, which in turn draws them both into a bizarre FBI conspiracy involving a Chevy Malibu with expensive (and deadly) extraterrestrial cargo in the trunk.

Otto aside, the movie itself is – and this is a technical term – punk as hell, thanks in large part to a near-perfect soundtrack featuring everyone from Circle Jerks to Iggy Pop to Black Flag. Brilliantly innovative use of a shoestring budget only adds to the DIY aesthetic; it’s a cheap movie at a meager budget of $1.5 million, but that money goes a long way.

The low-budget special effects, particularly in the unforgettable final scene, are reminiscent of sci-fi B-movies from the 1950s, but none of those movies were half as clever and biting as this one.

Alex Cox’s satire is aimed squarely at consumer culture, cold war nuclear fears, and conservative society in the age of Reagan, filled with unbridled rage even in its funniest moments. Ultimately, in its own strange way, Repo Man is a protest movie, albeit one of the most eccentric and purely fun ones in recent memory.

3. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968, Stanley Kubrick)

It’s no mystery why 2001: A Space Odyssey is widely seen as one of the greatest science-fiction films ever made. Stanley Kubrick’s excursion into outer space is boldly ambitious, visually stunning, and original through and through; it pushed the medium to its most awe-inspiring limits and set the stage for countless other films that aimed to tell bigger stories and ask harder questions of its audience.

In terms of scope, Kubrick didn’t exactly aim low; the film traces the entire scope of human history from our primate origins to our space-faring present and, eventually, our haunting encounters with other intelligent life.

So while it’s plainly clear why the film has earned so much acclaim, what is less clear is what any of it means.

While the entire nearly-three-hour film is filled with strange images and questions left unanswered, it’s the last half hour that stands out as the most baffling.

Without spoiling anything, the film goes out of control in spectacular fashion towards the end, seeming to defy all narrative logic and injecting the plot with some heavy symbolism that alters the meaning of everything that came before it.

Make no mistake, this more confounding final segment is the only way to end a film this ambitious and it’s far from a misstep; it stands as one of film’s greatest mysteries, seemingly impossible to decode and all the more fascinating because of it.

2. The Tree of Life (2011, Terence Malick)

Terence Malick doesn’t have a lot of fans anymore, and unfortunately that’s for good reason: his more recent films have without a doubt lost the charm and power of his early masterworks Badlands and Days of Heaven.

Instead they just retain the frustrating moodiness and self-conscious artiness that was peripheral to those films’ success; in other words, he’s fallen into self-parody and it’s unclear if he’s going to bounce back anytime soon, if ever.

His sole triumph of the new millennium is The Tree of Life, which backs up the occasionally frustrating quirks of his style with extraordinary emotional depth. The arty posturing is there, but for once it actually fits and works effectively in the context of the film.

Filmed in an impressionistic style that throws linear storytelling to the curb in a big way, the film is experiential in that the events of the plot aren’t necessarily shown as they actually happened, but rather how one of the characters might look back and remember experiencing them. The elliptical editing frequently jumps around in time between each scene to the point where the film borders on montage in many sequences.

As anyone who’s already seen The Tree of Life can tell you, there is in fact an actual, full-blown montage and it’s a doozy: the film, which opens on the grief felt by a mother after losing her son, cuts away from this story about a third of the way in to briefly depict the creation of the universe and the dawn of the dinosaurs.

The whole sequence initially comes off as jarring to say the least, but it’s all very carefully thought-out. Malick chose to juxtapose an incredibly intimate story of death and loss – the death of a child – with one of birth and creation – the big bang. In Malick’s own convoluted way, he’s inserting some hope and wonder into a story that would have otherwise been bleak and tragic.

Like Malick’s other recent films, The Tree of Life strives to be an art film with a capital A, which can make it a bit daunting for viewers not used to his ethereal, hands-brushing-against-fields-of-wheat-for-fifteen-consecutive-minutes style. Get in the right mood to watch it, however, and this is one of the most flat-out beautiful films of the last decade.

1. Inland Empire (2006, David Lynch)

The career of David Lynch is a long and strange one filled with films that seek to disturb audiences through oppressively dark atmosphere and an avant-garde sensibility.

Inland Empire is both his most recent film and the most extreme manifestation of his experimental tendencies; the plot, concerning marital infidelity and two actors (Laura Dern and Justin Theroux) who literally become lost in their parts and lose touch with reality, becomes secondary as Lynch establishes a stranglehold of intense dread that never lets up.

The film seems to exist solely in those tense few moments before a big scare in horror movies: there’s always a sense that something is lurking around the corner in every shot, but rarely does anything actually burst out from the shadows. It’s the cinematic equivalent of experiencing a nightmare in slow motion: a different, much more effective kind of terror than horror movies tend to employ.

Needless to say it’s easily the creepiest film David Lynch has directed, as well as his most challenging in many ways. The entire film is shot using a handheld digital camera, giving it the shaky, amateurish look of a snuff film at times, and the narrative becomes so abstracted as the film progresses that it borders on incomprehensible.

So yes, it’s impossible to make sense of, but it’s also wildly rewarding for fans of his previous work. This is David Lynch at his most alienating and unnerving; a decade later it’s unclear if Lynch plans on making another film, but if Inland Empire ends up being his final work then he surely went out with a bang.

Author Bio: Joey Shapiro is a film student at Oberlin College in scenic Northeast Ohio, the cornfield capital of the world. His dream date would be watching all thirty Godzilla movies in a row.