The idea for this list originated from an interview Stanley Kubrick gave in the late 1960s. He was in pre-production for his ambitious screen biography of Napoleon. During the interview Kubrick explained that a truly great historical film had never been made. He provided two reasons to support his claim: 1) a failure to convey historical information in an interesting way and 2) failure to establish a sense of reality about the historical time period.

Although Kubrick’s Napoleon project eventually fell through, he planned to portray the Napoleonic era with the utmost accuracy. When Kubrick finally made his historical epic Barry Lyndon in 1975, the depiction of history left his peers in the dust.

The following list are films that have represented history since Kubrick made his criticism of historical film. The only exception being the Tartovsky film Andrei Rublev which was released in 1966 (not until 1973 in America), but pivotal nonetheless. Not all of these films necessarily met Kubrick’s criteria for clarity and reality, but they did bring history to the screen in unique and creative ways.

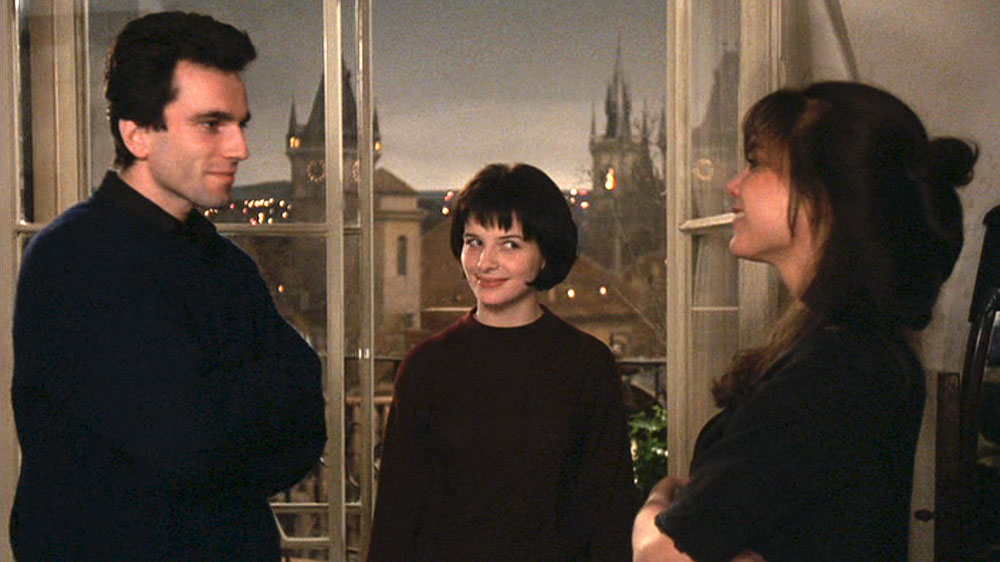

15. The Unbearable Lightness of Being (Phillip Kaufman, 1988)

Set in the charged political environment of Prague, Czechoslovakia right before the 1968 invasion by the Soviet Union, The Unbearable Lightness of Being tells a complex love story with history as backdrop. Passionate performances from Daniel Day-Lewis, Juliette Binoche, and Lena Olin reinforce the Romantic and Existential themes of the story.

Tomas (Day-Lewis) is a womanizing brain surgeon who avoids committed relationships until he meets country girl Tereza (Binoche and they eventually get married, but his philandering continues. His former lover Sabina (Olin), a Bohemian artist who lives a detached existence, remains involved in their marriage. After the Soviet invasion Tereza finds her calling as a photographer in a spellbinding sequence that mimics archival footage from the 1960s.

Tomas gets in trouble the Soviet authorities over an article he wrote that criticized the regime. After Tomas refused to sign a retraction of article the Soviets took away his medical license. Despite the loss of his social status Tomas continues to live with intelligence and passion, in spite of what the state did to him.

No one can control what set of social and political circumstances they are born into. Regardless of their circumstances, everyone faces the same challenges of love, family, relationships. People must be strong for each other and be mindful that life is worth living with intensity and passion. Phillip Kaufmann did a masterful job of adapting the Milan Kundera novel.

14. Zero Dark Thirty (Kathryn Bigelow, 2012)

Bureaucrats and intelligence analysts wage the War on Terror in Kathryn Bigelow’s sublime Zero Dark Thirty. The heroes and heroines in the film are attractive, educated, well dressed, and driven towards a common purpose. Jessica Chastain personifies the ethos of the war on terror as Maya, a prodigy intelligence analyst who pursues the 9/11 conspirators with a stoic determination.

The history of the early 21st century unfolds in Zero Dark Thirty through clipped cell phone conversations, text messages, encrypted emails, sometimes interrupted by spastic violence.

At first Maya is troubled by the interrogation technique of water boarding but eventually comes to embrace torture as a necessary evil of the shadow war. A good portion of the intelligence work appears tedious: watching surveillance videos and monitoring email traffic. Maya and her colleagues are all tech savvy, multi-lingual – the Centurions of the 21st century.

Bigelow’s documentary style camera style adds an immediacy to the action. Mark Boal’s script does a superb job of conveying the complex historical information and the machinations of the intelligence community. The neutral colored production design adds a sense of gloom to the grim subject matter.

There’s a subversive undercurrent to Zero Dark Thirty as well. The ominous music of Alexandre Desplat could be used for a horror film, especially the John Carpenter flourishes during the Bin Laden raid. The American Empire feels fragile as it compromises cherished values en route to a hollow victory.

Even the controversial final sequence, a reenactment of the raid on Bin Laden’s compound moves along without a sense of triumph or fanfare. Just business as usual. The film ends with Maya contemplating the end of her mission in an empty airplane. The uncertain emotional beat of the conclusion leaves a haunting feeling.

13. The Hateful Eight (Quentin Tarantino, 2015)

In the Hateful Eight Quentin Tarantino distilled the primal conflicts of American history into a three hour film set almost entirely in a log cabin. The film begins with the classic set up of a Gunsmoke or Bonanza episode: strangers with a past in the Western frontier are thrown into a desperate situation.

Tarantino’s previous two films had both dealt with historical justice: With Inglorious Basterds the Jews get revenge on the Nazis and African-American slaves get their satisfaction in Django Unchanged. In The Hateful Eight the morality gets twisted even further: there are no heroes or villains. Redemption is not in the cards for these characters.

The conflicts are set up in the first half hour, beginning with the ominous close up of a stone statue of Christ being crucified. A carriage carrying the grouchy Bounty Hunter John Ruth(Kurt Russell) and his fugitive Daisy Domergue (Jennifer Jason Leigh) cross paths with Major Warren (Samuel L. Jackson) and then are joined by Sheriff Mannix (Walton Goggins).

Major Warren was purportedly a correspondent of President Abraham Lincoln and a fierce Calvary officer for the Union Army, while Sheriff Mannix fought as a Confederate raider.

The Godlike-Satanic figure of Major Warren is determined to exact revenge on those who wronged him. The conversation in the carriage quickly goes back to the Civil War where all characters had some stake. Daisy is the antithesis of a Southern Belle, she’s a foul mouthed racist. Sheriff Mannix is willing to let bygones be bygones.

Once they arrive at their destination, Minnie’s Haberdashery, others enter the story. It’s clear no one is who they appear to be. As a blizzard closes in, tensions reach the breaking point, blood and guts begin to spill.

The Hateful Eight may be Tarantino’s most audacious film to date. Abandoning the epic scale of his previous two films, here Tarantino places his characters inside a closed universe. The deeply ingrained political and racial tensions among the Hateful Eight stem from the conflicts of America’s complex history.

Whether anything gets resolved is left up to the viewer, but the extreme violence buried deep within these vicious characters leaves much to ponder. Tarantino’s ability to call upon old forms to break new ground is on full display.

12. American Graffiti (George Lucas, 1973)

Few art forms channel feelings of nostalgia like cinema. American Graffiti looked back at a specific moment of the past, a summer night in 1962 told from the perspective of 1973. Lucas’s autobiographical portrayal his own youth in Modesto, California used multiple story lines, a departure from the way mainstream films were made at the time.

The use of pop music proved another brilliant innovation. The jukebox music serves as a stream of consciousness to drive the action while creating a striking verisimilitude of time and place. Haskell Wexler’s cinematography brought a documentary feel to American Graffiti.

The talented cast often improvised their dialogue. Intellectual Curt (Richard Dreyfuss) and class president Steve (Ron Howard) weigh whether to leave for college. The aging greaser John (Paul Le Mat) reflects on life passing him by and nerdy “Toad” (Charles Martin Smith) grows up. Ahead of them lay the rest of the 1960s, Lucas managed to create the sense of time passing in a warm and jaunty representation of a historical moment.

11. Russian Ark (Alexander Sokurov, 2002)

Already a landmark film of the 21st century, Russian Ark unfolds in one continuous shot filmed in real time. Filmed at the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia, Sokurov’s film glides through the entire history of his country. The camera follows the character known as “The Stranger” through the museum’s labyrinth as he encounters various figures from the past. Time loses all meaning as he steps into different eras, some more enticing than others.

Russian Ark explores how history shapes individual and national identity. Questions are raised on how the past shapes the present as well. What is remembered? What is forgotten? Spellbinding sequences with hundreds of extras attack the eye with color and movement, while some of the encounters are intimate, moving, even awe inspiring. Sokurov’s experimental approach to engaging with history will hopefully influence the cinema of the future.

10. JFK (Oliver Stone, 1991)

Oliver Stone’s controversial JFK is a journey into the rabbit hole universe of the John F. Kennedy assassination. Stone crafted a narrative chaos with countless story lines that contradict each other.

Kevin Costner star as real life New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison who pursued his own investigation of the JFK assassination due to his skepticism of the government approved Warren Report. As Garrison pursues the case everything points to a conspiracy at the highest reaches of the American government.

There’s no doubt JFK is a vibrant film from beginning to end, yet its legacy is somewhat dubious. Today conspiracy theories have gone mainstream and are part of everyday parlance. Can the government be trusted? Are “shadow governments” in control?

JFK’s relentless examination of the corridors of power are a plea for citizens to stay vigilant and hold government officials accountable. But obsessions with conspiracy theory can also lead to an ultra skepticism for the misguided- making them susceptible to the rants of a demagogue.

JFK incorporated all sorts of styles including historical reenactments, long monologues, archival footage, trial scenes, flashbacks, and new leads for every dead end. Full of virtuoso performances and impressive camera work, Oliver Stone used history as a playground in a Quixotic search for the truth not necessarily designed to popularize conspiracy theories, but to further an understanding of the post-modern reality of narratives in collision.

9. The Grand Budapest Hotel (Wes Anderson, 2013)

Wes Anderson’s colorful and imaginative film about Europe during the Interwar period features his trademarks of stylized storytelling and flashy performances, but also engages with the darker forces of the 20th Century. M. Gustave (Ralph Fiennes) manages the Grand Budapest with grace and style, a place that symbolizes the height of civilization in the maelstrom of 1930s Europe. Anderson pits chaos and civilization in conflict as a central theme The Grand Budapest Hotel.

Like Tarantino, Wes Anderson’s films exist in their own niche universe. Sequences recall the goings on at the Grand Budapest Hotel and the numerous intrigues happening within its orbit: scandalous affairs, a disputed inheritance, a mentor relationship, a surreal prison break, and the ominous rise of Fascism.

Steeped in the cadences of 1930s cinema, the artificial world of the Grand Budapest comments on the difference between “movie reality” and reality itself. Watching a plethora of movies can blur the difference between the two.

At the same time movies tend to foster nostalgia and mythology. Anderson uses the artifice of cinema to shine light on the tragedy of modern history. Movies can serve as an escape from the real world, but can also be a portal to some understanding of reality. When the fantasy and reality collide the results can be both wondrous and tragic.

The Grand Budapest Hotel, besides being one of Anderson’s most entertaining movies, also manages challenge his audience to look outside his own creations.