8. Ray Winstone in Nil by Mouth (1997)

One of the best one-off directorial efforts (from actor Gary Oldman), this personal and unrelenting film doesn’t disguise the horrible way of life this family must endure in their South East London council estate.

Amidst issues like low income and drug abuse comes the tyrannical monster that is the abusive patriarch, Ray, who’s more foul-mouthed, more vulgar, and more prone to utter outbursts of violence than anyone else. He sees the world and the people that inhabit it as hostile and getting in his way, so he lashes out against these injustices in misguided and misdirected manners, usually by beating up those weaker than himself.

Winstone bravely embodies this unlovable and reprehensible character and manages to give him a semblance of sympathy without reducing the monster that he is.

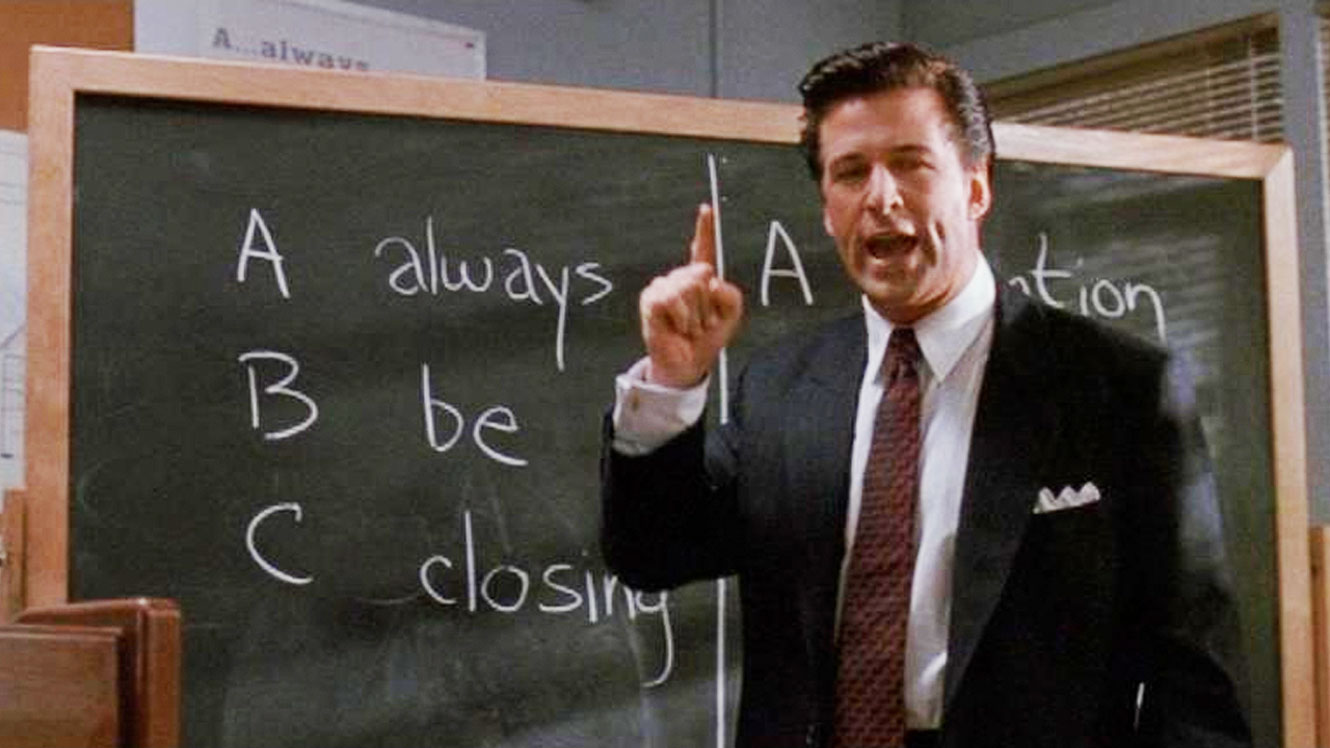

7. Everyone in Glengarry Glen Ross (1992)

When you have a screenplay as good as one written by David Mamet, you’ll want to make sure you get some good actors to realise it.

Glengarry Glen Ross gets some of the finest actors from different generations and has them performing at the top of their game: there’s Jack Lemmon, seemingly a precursor for Gil from The Simpsons, who’s nick-named The Machine, yet machines aren’t often as wheezily whiney as this over-achiever past his time; there’s Al Pacino as Ricky Roma, the almost constantly calm and reassured out of the bunch who was born to have Mamet-written dialogue come from his mouth.

Ed Harris as Dave, whose performance gets more and more fun to watch as he just gets more and more frustrated with the injustices and hard luck his job serves him; Alan Alda as George, the most nervous of the group who is constantly trying to keep up with the aggressiveness of his work environment; and there’s new-ish actor Kevin Spacey as John, who firmly holds his own against the giants he’s up against, even repetitively shutting down Jack Lemmon in a lengthy arduous one-on-one sequence.

Ohh, and Alec Baldwin in a show-stopping small role as Blake, the “motivational” speaker who brilliantly lectures us all on the virtues of brass balls. Such a great collection of superb actors with the foundation of a perfectly pitched screenplay of diatribes and cynicism, all given free reign by some appropriately reserved direction, is a real blessing the cinema received during the ‘90s.

6. Benoît Poelvoorde, Man Bites Dog (1992)

This very low-budget and low-concept film caused a sensation upon release due to its stark and up-front faux-documentary portrayal of a demented serial killer, Ben, who seems like an ordinary bloke in real life.

Man Bites Dog (also known as It Happened In Your Neighborhood) was a collaborative effort from a small crew of young men, including Benoît Poelvoorde who not only starred in the lead role, but also did a bit of co-directing, co-writing, and co-producing – but we’ll focus on his main talent since his performance as Ben is a stunningly disturbing new take on the serial killer character. Immediately we see the joys Ben puts into his craft, appearing malevolent and cheekily psychopathic as the “doco” crew follow him around as he takes pride in his liberation by killing whomever he feels like, putting in more effort into his murders than his piano lessons or boxing matches.

Poelvoorde’s acting style at first seems exuberant and performative, but as the film progresses the subtleties in his unhinged and deeply troubling psyche become more apparent – Poelvoorde manages to convey both the extroverted playfulness of his character and his disturbed rotten core.

5. Nicolas Cage, Bringing Out the Dead (1999)

Both an underrated Scorsese film and Nicolas Cage film, it’s a shame that their only collaboration isn’t more widely seen. Bringing Out the Dead sees Scorsese, hot off the heels of Goodfellas and Casino, in an even more exuberant mode than usual, and Cage fits like a glove in this starring anti-hero role.

Frank Pierce is another one of Paul Schrader’s lonely men, the fourth collaboration between the screenwriter and Scorsese to make a film (and a masterpiece of one) about these disenfranchised men – one of them was Jesus, and one of them was a guilt-ridden ambulance driver whose cynicism and pessimism can’t stop him from trying to save a few lives, with no-one more suitable for that kind of role than Nicolas Cage (on a good day).

His sleep-deprived Frank is so desperate to be fired, but feels forever damned to his occupation. His stressful job in the bloodiest and most squalid areas of New York drains him of his hope, but occasionally fuels his god complex when he manages to save someone’s life.

Cage brings to life this desperation for redemption (or at least a good sleep), bringing his usual eccentricities as an actor and reigning in the insanity by the right amount (as well as the humour, and thankfully there’s a lot of humour in this dark film).

Though Nicolas Cage and Martin Scorsese had achieved popularity and mainstream exposure when making the film, it still flopped at the box office and has since remained both of their most undervalued films – hopefully more people can become aware of this grisly, yet simultaneously exciting and important piece of work with a stellar performance at its centre to guide it all.

4. David Thewlis, Naked (1993)

Mike Leigh’s films, whose dialogue is often improvised by the actors during rehearsals, often delegate this dialogue amongst a variety of differently opposed characters. In Naked, much of the dialogue of this scarcely cast film is given to David Thewlis’ Johnny and his constant barrage of rants and ravings about modern day ennui, pointless jobs, the transient nature of time, and apocalyptic conspiracy theories.

He moves about wildly from his ex-girlfriend’s flat to the decrepit part of the city to an empty building being guarded at night to a coffee shop to the waitresses’ place and then back home at his ex-girlfriend’s, all the while snarling out at anyone that will listen his incisive and furious stream-of-consciousness monologues that he’s kept bottled up.

He seems to produce thoughtful, nihilistically philosophical tirades, but not many people around him can keep up with his gloomy worldview, let alone get along with his aggravated and unorthodox manner of delivering these sermons.

Johnny always has someone to talk to, even if they’re not listening, but he is still a lonely figure in the world, unable to communicate in the way that only he can with everyone else. He’s an anomaly, a poor intellectual, a thoughtful individual who can’t put his mind to good use, and Thewlis perfectly gets across this sense of dysphoria in just the final shot of the film alone.

3. David Wenham, The Boys (1998)

It’s likely that David Wenham, along with Ben Mendelsohn, is another Australian actor on his way to international acclaim, and he already has a wealth of diverse acting roles from his home country. The one that put him on the map was The Boys, which could be seen as his break-out role. He had appeared in the play the film is based on, which controversially first played in 1991, and all that time for preparation shows in this subtly terrifying performance.

There’s a steady, linear, and futilely hopeless transition in character for Brett, after leaving prison for assault charges up until he’s arrested again for much more serious assault charges. Upon arriving back home, he displays his inner assertive-aggressiveness that he subdues with his affection for the family that not only protect him from his criminal ways, but exacerbate them.

Brett shows affection towards those in his family and living in their house, especially towards the women, but it’s the women he disregards the most as his affection is often simply a ploy to continue his own solipsistic self-satisfaction. There are unfortunately people like Brett out in the world (the story of this film was based on an actual crime) and it was up to Wenham to bring the sort of character you don’t want coming home to life.

2. Philippe Nahon, I Stand Alone (1998)

A quintessential actor of New French Extremity, Philippe Nahon’s terrifying performance as the Butcher in I Stand Alone is so sharply fierce and so indicative of a man reduced to a monster by his surroundings, you think he’s going to jump out the film and strangle you. Early on, the Butcher does not do much to make the viewers relate to or think kindly of him, but we’re stuck with this man throughout the entire film and it’s up to Nahon to vivisect this character and unearth his reasons.

A large part of the film is narrated by the Butcher, letting us into his head as we observe him in his regular routines, trying to scrape some money together. His voiceover reveals the intense dissatisfaction he has with his work, his family, his friends, and his life. This almost constant voiceover takes this dark existential drama into almost horror territory due to Nahon who, though never shouting, brings out the underlying fury in just his voice, pairing up well with his barely stoic on-screen presence.

I Stand Alone is an excellent film about depression and loneliness, though not one that is an easy watch at all, yet Nahon is what makes so much of the film and its deeply introspective screenplay work. He has crafted a serious vision of a character who is at all odds with the rest of the world.

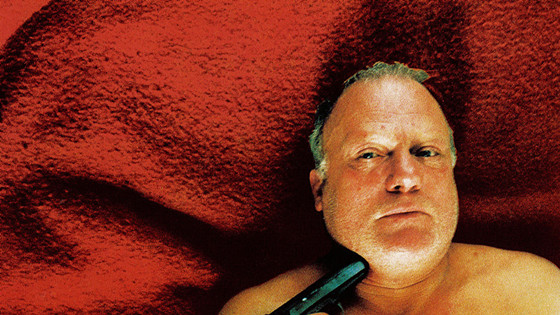

1. Harvey Keitel, Bad Lieutenant (1992)

There hasn’t been quite a redemption like the one Harvey Keitel’s unnamed Lieutenant character had. The somewhat spiritual denouement of Bad Lieutenant is something to be seen to be believed, and it wouldn’t have been as profound if not for the stark and utterly pained performance from Keitel.

Right from the beginning, we see the Lieutenant bathes in his own misery and self-destruction, almost endlessly drinking, snorting, smoking, and a little injecting himself along as he tries to pay off his gambling debts and solve the case of a raped nun (the reward money of such may help him out with the former problem). But Keitel shows that the Lieutenant cannot get the world to work for him, so he aggravates his bad luck with his harmful vices.

Never has such a downward spiral featured this much existential frustration – Keitel somehow manages to contort his face into a grotesque series of pained expressions, along with a few bellowing cries demanding salvation. It is a harrowing, yet maybe cathartic, sight to see.

Roger Ebert ended his 4 star rating of this film with “Keitel has given us one of the great screen performances in recent years” and he more than anyone would agree the early ‘90s contained some very strong acting from American men.

Keitel’s acting has stunned serious movie-goers since his debut in Scorsese’s Who’s That Knocking At My Door and this film (directed by another great Catholic American with Italian heritage) showcases what is likely the very best acting performance from one of the greatest actors of this decade.

Author Bio: David Morgan-Brown is an Australian lover of movies, films, flicks, and kino pictures. He does written reviews for Colosoul, video reviews for Flim Reviews, and does comedic skits with his mates for Carpool — go laugh with (or at) him.