Audiences like films for all sorts of reasons. Stunning performances from favourite actors and actresses, technical dexterity from the part of the editor, the creative mastery of the composer who embellishes the film with its expressive music are only a few of the factors that can make a movie memorable and adored. But there are also these films that look like paintings, like works of art that feed our senses and satisfy our aesthetic needs.

East Asian movies are becoming more and more popular in the West, their fandoms growing rapidly every single day. Part of this may well be due to the level of innovation found within these countries’ film industries, next to the comparatively stale and predictable tendencies of mainstream Hollywood directors. Japan, South-Korea, China, Hong-Kong and Taiwan are not afraid to experiment, crossing borders and breaking cinematic conventions.

East Asian cinema is inventive and original to the core but there is one additional element that makes it so captivating.

That would be that its films are eye-candies; the picturesque landscapes and architecture of Asia in combination with the warm and lyrical aesthetics that its film-makers favour and the powerful mise-en-scènes that they fabricate contribute to a visual outcome that is poetically beguiling.

This list features only some of the most prominent visually stunning films that come from East Asian countries.

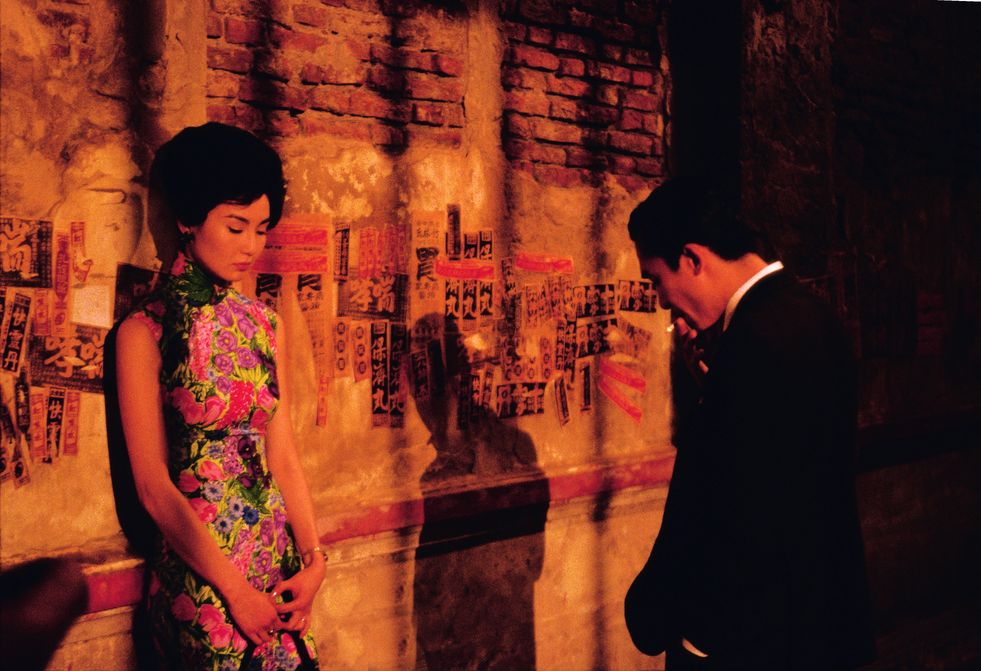

1. In the Mood for Love (2000, Wong Kar-wai)

Every single film that Wong Kar-wai has made is more or less inconceivably seductive. There is something about the saturated colours, the old-fashioned wall tapestries, the dim retro lights and the stylish clothes of his actors and actresses that creates a visual arrangement that is able to enthral even the most unblinking viewer.

What should be known, though, is that a huge part of Wong’s aesthetic universe owes its magical appearance to William Chang; the art-director, editor, costume and production designer of most of his films.

In the mood for love is a gorgeous film. The monumental step-printed slow motion sequence with Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung on the stairs of their apartment complex, accompanied by the sensational music of Shigeru Umebayashi is only one of the visual highlights of the film.

The cheongsam dresses of the heroine and the beautiful costumes of the hero make them one of the most stylish cinematic couples in the history of cinema and the colours that Wong chooses frame their romance with inviting warmth and passion.

2. Dolls (2002, Takeshi Kitano)

Dolls is one of the most lyrical and poignant films that Takeshi Kitano has created, revolving around the love stories of three different couples. It opens with a performance of a Bunraku puppet theatre that connects the different plot-lines of the movie, dressing it with a theatrical elegance which speaks of the tragedy of fate.

A big part of the film’s visual intensity comes from the movement of its heroes. The protagonists are using their own bodies a puppet-like manner, reinforcing the central theme of the film.

But Dolls also has beautiful vivid colours that can be found everywhere, ironically juxtaposing the melancholy of its main characters.

The red leaves of the autumn trees and petals of flowers, the snowy ground of frozen mountains, the vibrant masks of demons and pandas and the deep-coloured clothes of the heroes, all contribute to the establishment of a uniquely expressive aesthetic.

3. Three Times (2005, Hou Hsiao-Hsien)

Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Three Times, just like Kitano’s Dolls, narrates three different, deeply moving love stories.

The Taiwanese auteur chooses to use the same actor (Chen Chang) and actress (Qi Shu) in all of them, commenting on the nature of time, coincidences, passion and sorrow. The visual beauty of the film springs from various choices by Hou and his highly talented cinematographer, Mark Lee Ping Bin.

Three times exhibits a masterful and eloquent use of lighting. The interplay between its absence and presence elevates the facial expressions of the heroes when they pass from light to shadows.

The art direction of the film is also noteworthy; the decoration and composition of its mise-en-scènes and the stylish costumes of the protagonists make it irresistibly attractive and perfectly capture the spirit of three different eras of Taiwanese history.

4. Harakiri (1962, Masaki Kobayashi)

Kobayashi was a director whose films were deeply theatrical, reminiscent of ancient Greek tragedies. His movies are filled with lyrical shots with symmetrical compositions that make them visually stunning.

Harakiri is a characteristically graceful piece of Kobayashi’s work, one of his valuable contributions to the jidaigeki film genre, telling the story of a destitute samurai requesting a place to honourably commit suicide at the manse of an established samurai clan.

Harakiri takes advantage of the beautiful landscapes of the Japanese countryside to build its beautifully poetic and intense fighting scenes. At the same time, it uses the geometric interior spaces of the Japanese houses as minimalistic frames for the development of the plot.

It also plays with the light in order to make its heroes’ expressions highly dramatic, upraising their emotional capacity. Kobayashi’s film is undoubtedly one of the most good-looking samurai films, cleverly paying attention to detail.

5. Ugetsu monogatari (1953, Kenji Mizoguchi)

Ugetsu monogatari is another unconventional contribution to the Japanese period drama genre, masterly delivered by the great Kenji Mizoguchi. Two couples of villagers, followed by a naive man who wishes to become a samurai, see their lives take an unexpected turn when their village is attacked and looted by a group of soldiers.

The film has elements of a horror film, of a drama and an action film at the same time. Its visual beauty, thus, is the outcome of the combination of atmospheric scenes, expressive close-ups and dynamically rapid sequences.

From the haunting sequence where the boat of the villagers is floating in a foggy lake, to the dreamlike scenes where one of the men is seduced by a mysterious rich woman, Ugetsu is poetically emotional, using images more than words in order to build its potency. Mizoguchi’s masterpiece looks like a painting, mesmerising and powerful in its simplicity.

6. Branded to Kill (1967, Seijun Suzuki)

The 60s were a golden decade for Japanese cinema, filled with experimentation, innovation and a rebellious spirit. Seijun Suzuki was one of the most prominent representatives of that era, his films suffused with quirkiness and style.

Branded to kill is a radical yakuza film, charged with absurdity, humour and action. Plenty of its shots and frames look like collages or surrealistic dreams, perfectly supported by the black and white colours that Suzuki chooses to use.

A clumsy and goofy hit-man tries to keep his patience when he has to deal with his unstable wife, a murderous femme fatale and the unexpected turn that one of his killing contracts takes.

Suzuki employs a wide variety of cinematic techniques; its angles and frame compositions are reminiscent of those of German expressionism, its close-ups seem to be parodying the film-noir genre and the editing defies the laws of continuity. Branded to Kill is visually stunning in an unconventional way, befitting the personality of its creator.

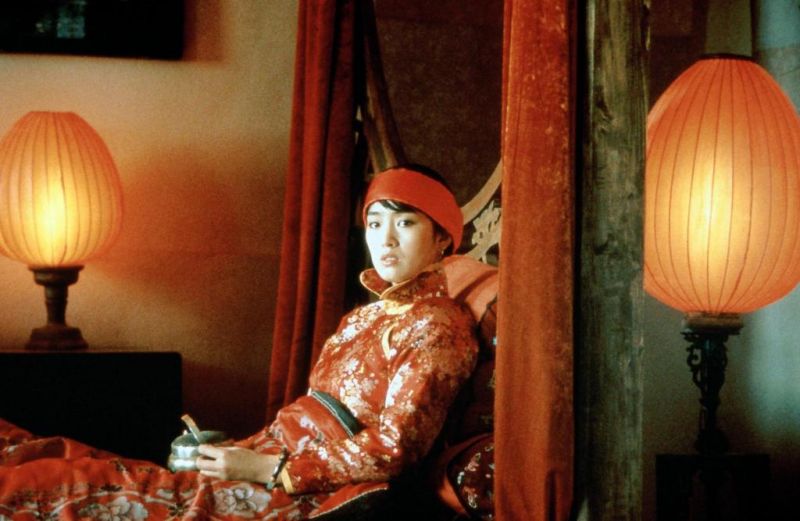

7. Raise the Red Lantern (1991, Zhang Yimou)

Being one of the most recognised and acclaimed film-makers of East Asia, Zhang Yimou has created plenty of visual stunning films whose beauty seems to be unrivalled.

Their trademark is the perfectly choreographed fighting scenes, given with beautiful colours in the midst of captivating natural landscapes. But before Hero, House of the Flying Daggers and Curse of the Golden Flower, Zhang created a series of dramatic films, with no epic elements but still pleasing to look at.

Raise the Red Lantern follows the life of a young woman who is made to become the wife of a rich and powerful lord. The heroine’s tension and passion is eloquently expressed by the saturated colours of the film and the astonishingly perfect frames of Zhang.

The film may not have poetic fighting scenes but the tendency of the director to choreograph the movements of his actors and actresses is expressed through majestic ballet sequences.