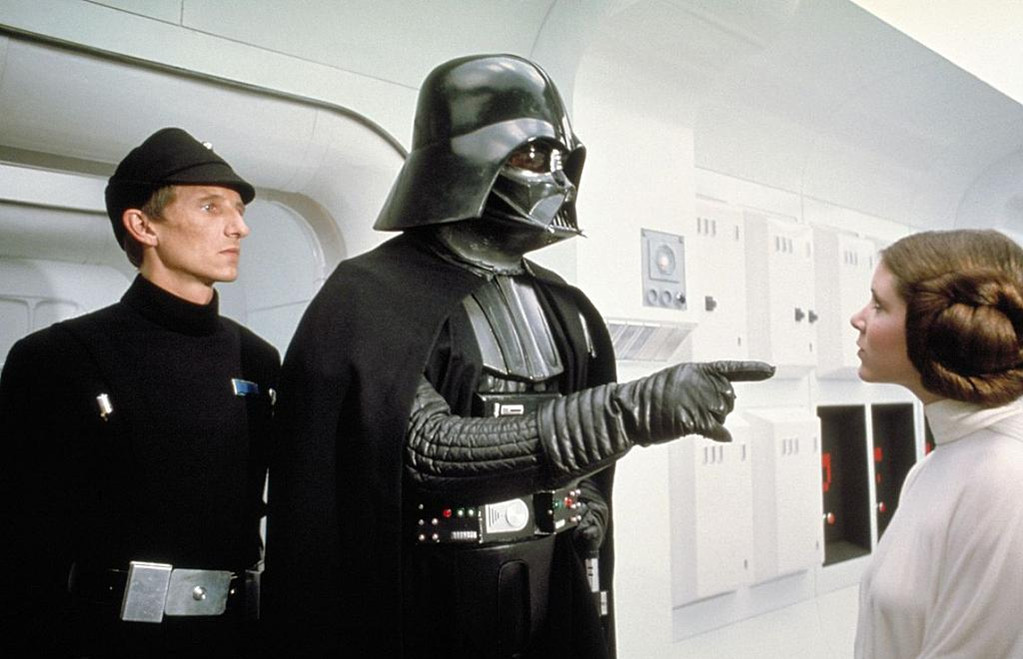

14. Darth Vader in Star Wars (1977)

Star Wars was a film solidly carpentered on iconic elements from film, culture, and mythology. Everything in it was meant to be an ultimate symbol and/or type. It is no accident that the series’ great villain is the most villainous bad man of them all. In point of fact, three performers were required to bring this uber-villain to life.

Tall, imposing actor David Prose (also a body-builder), stunt man Bob Anderson and the unforgettable and resonant voice of the noted actor James Earl Jones were blended together to create Darth Vader. In the first film (now known as Episode IV), the character is much referred to in the opening minutes and, from the visual and verbal evidence of his doings, he is not a force with whom one would wish to cross swords.

After a battle with the starship carrying Princess Leia (Carrie Fisher), which his forces win, the character’s arrival is announced to the now captive heroine. The automatic doors of the suite open to reveal an improbably tall figure clad from head to toe in black.

Even more striking, his face is completely obscured with mask fastened into a helmet. The mask contains a breathing device (much later in the series, the viewer learns of the incident which necessitates this gear). His labored breathing, deep and distinctive voice and undeniable appearance mark him from the start as the mighty force who will be the springboard of this legendary series’ action.

13. Grace Kelly in Rear Window (1954)

For decades many film historians and fans have gripped that Judy Garland was gypped of the Oscar for which she was nominated (for A Star is Born) when it was given to Grace Kelly for her largely glamour free turn in The Country Girl. If that were all there was to it, they would be right. However, Kelly also won the New York Film Critics best actress prize as well that year.

That body gives awards for a recipient’s body of work in a given year and they cited not just The Country Girl but the two films Kelly made that year with the great suspense director Alfred Hitchcock, Dial “M” for Murder and Rear Window.

These two films and the next year’s To Catch a Thief showcased Kelly as the quintessential Hitchcock blonde, one of the great staples of film history. If that isn’t worth a prize, what is? Their finest hour (and one of Hitchcock’s best ever) was Rear Window and Kelly has the best entrance of her career.

The photographer character played by James Stewart is laid up with a broken leg resulting from the events surrounding the action pics he routinely takes. This leaves room for his ultra-glam fashion editor girlfriend to move in on him to campaign for marriage. She is much talked about before she shows up.

The photographer is asleep when he is awakened by what at first looks like a continuation of a dream. A most lovely blonde woman, dressed in an ultra-stylish black and white dress, is kissing him (in slow motion). She mock-introduces herself by saying “From top to bottom: Lisa, Carol, Freemont”, as she twirls around. One can only wonder, after that, why the man is resisting.

12. Sean Connery in Dr. No (1962)

A certain segment of the world knew James Bond, as a character, long before the cinematic world introduced him into that fold. Bond had been the hero of several well regarded action suspense novels by British author Ian Fleming involving the superspy’s amorously tinged adventures and battles against supervillians of all kinds.

When President John F. Kennedy, arbitrator of style, among other things, proclaimed his liking for the books, they were set on the path to mega-success, including the movies. (In fact, there had been a live TV version of Fleming’s Casino Royale with American actor Barry Nelson as a rather unlikely Bond.) When Bond was introduced (rather uncertainly) with Dr. No, many wondered who would play the spy.

The choice was a little known Scottish actor named Sean Connery (then best known as the younger leading man of the Disney film Darby O’Gill and the Little People). The darkly dashing thespian doesn’t have the self-contained pre-sequence mini-adventure which would be a trademark of the series thereafter. Instead, the character is introduced several minutes into the film, after a related, action-filled tangent set in Jamaica, has played out.

Bond, elegantly tuxedoed as ever, is sitting at the baccarat table coolly sparring with a luscious brunette beauty (a character who appeared in the next Bond film and who was to have been a regular until that idea was dropped). The character successfully bluffs his way through both the game and the woman’s heart. Thus, an iconic character was off to a perfect and appropriate start in films.

11. Harrison Ford in Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981)

Steven Spielberg’s history as Hollywood’s foremost populist film maker seems so golden in retrospect (even though it’s still ongoing) that many younger fans may not remember that he once had a dark period indeed. He had just directed his first comedy (and virtually last), the disastrous 1941. It was such a flop that many actually thought him through but old pal George Lucas took him under his wing and steered him into making a crackerjack adventure film inspired by the serials and B-action films of long ago.

The picture, Raiders of the Lost Ark, centered on a 30s professor/archeologist named Indiana Jones, who sedate, composed, proper (if handsome)in the classroom but an ultra-virile, whip-wielding man of action out in the field as he tracts down and retrieves priceless and magnificent ancient artifacts.

When the original plan to cast TV star Tom Selleck fell through (lucky, lucky them and us), Spielberg and Lucas turned to a featured player from the Star Wars series, Harrison Ford. Ford had yet to truly breakthrough (and, as was seen clearly as time went by, just being in Star Wars didn’t make a star). However, the film introduced him and Dr. Jones with a wild, marvelous mini-adventure at the start of the film. Indy is tracking down a small but legendary golden idol deep in the Amazon.

There are deadly natives to get past but also a trap involving a giant runaway boulder and a snake pit, among other hazards. The intrepid adventurer ably gets through them, though showing a touching human side in his exposure to danger. This reel had more action, spectacle and thrills than most whole films contain. However, for Indiana Jones, Harrison Ford and company, and the viewers, the adventure had just begun.

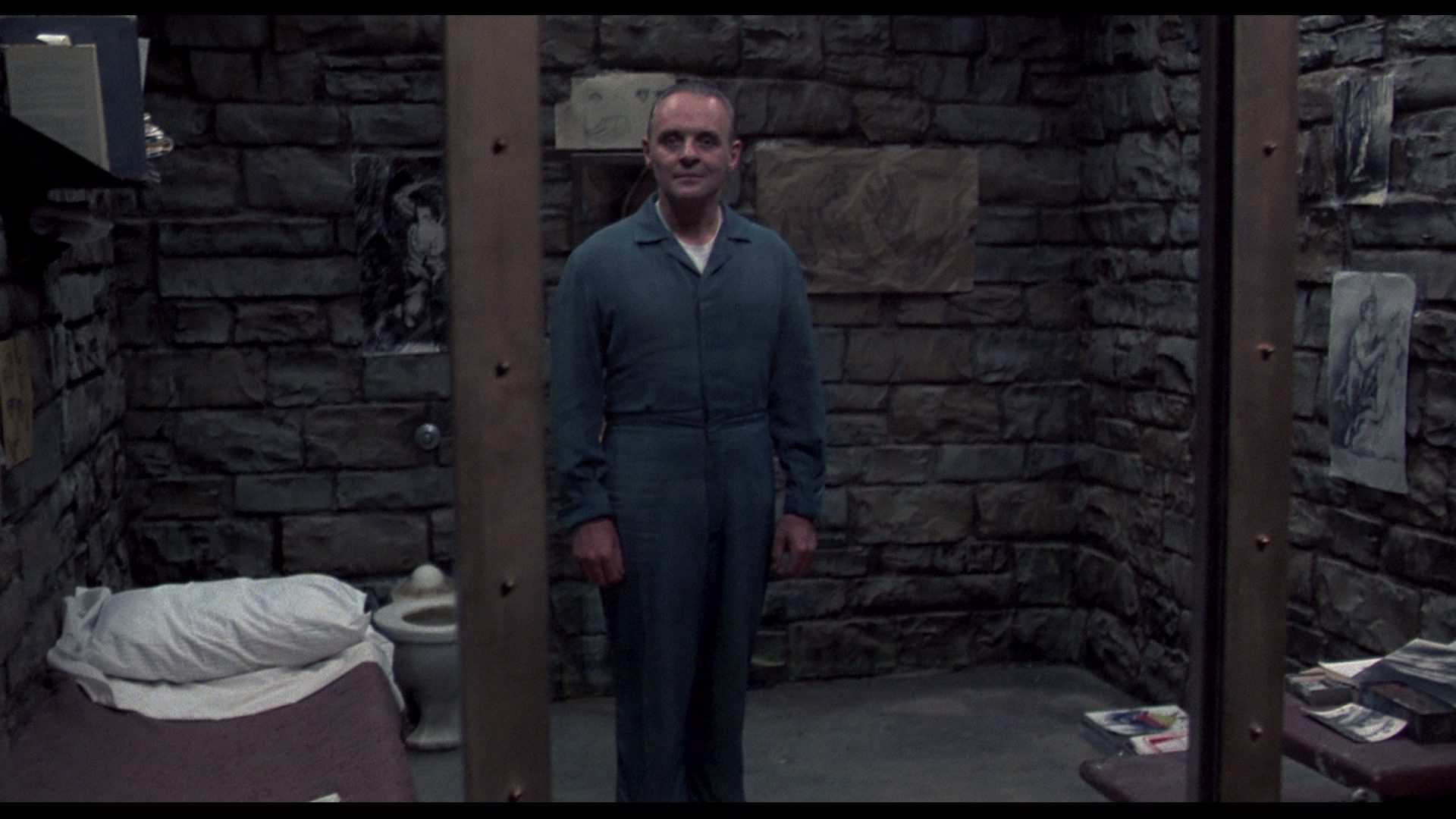

10. Anthony Hopkins in The Silence of the Lambs (1991)

Novelist Thomas Harris was surprised when the hit element of his novel Red Dragon was not the conflicted savant hero or the gothic, colorfully deranged main villain but a minor character. This character was an institutionalized, brilliant psychiatrist who was equally deranged. This was Dr. Hannibal Lecter, not known as “the cannibal” for nothing.

The character first saw the light of the movie screen in director Michael Mann’s stylish adaptation of Red Dragon, 1987’s Manhunter. The character, presented as an inmate in a sterile white cell, per the book, and was played by British actor Brian Cox and it was rather good according to critics and the discerning few who saw it, but it changed no one’s life.

The next sighting of Dr Lecter would be far different. Harris crafted a follow-up novel entitled The Silence of the Lambs which featured a new lead character, a young female FBI agent in training, who goes to visit the bad doctor in hopes of picking his brain in order to catch a particularly nasty serial killer. This book was an even bigger hit than it’s predecessor and the proposed film version attracted even more prestigious talent to the project.

Director Jonathan Demme knew that Lecter must have a star presence, though he would actually be on screen for about ten minutes (but what minutes!). He chose the distinguished theater, TV, and sometime film actor from the UK Anthony Hopkins, who had yet to have a film breakthrough. He subverted the book (and conventional wisdom) by housing Lecter in a dungeon like cell in a Victorian mental hospital, much like the ogre the character is reputed to be.

When Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster) comes to visit, she is briefed for several minutes about the doctor’s wildly evil (and imaginative) exploits before meeting the madman himself. Clad simply in white tee-shirt and pants behind a Plexiglas barrier, he initially seems anti-climactic.

However, once he starts talking, seemingly reading the young woman’s mind and playing on her darkest fears, one sees that he lives up to advertising. The visit quite unnerves Clarice but the viewer can hardly wait for the next visit to the cell. Lecter is on his way to folklore legend (though he, frankly, has outstayed his welcome a bit by now).

9. Charles Chaplin in City Lights (1931)

Charles Chaplin wore many hats in the film world including those of producer, director, screenwriter, and composer, in addition to being a performer. He was widely labeled a genius for many decades and is still considered so as a performer. However, some now say that he was somewhat less inspired in some of the other fields. However, he did know how to do one thing better than pretty much anyone else in the world: he knew how to handle one of the world’s great performing talents.

By the time he created City Lights, his masterpiece according to many viewers and historians, he had long been not only one of the world’s greatest film stars but one of the most celebrated people in the world period. However, his fame was forged in the silent era and City Lights would premiere after the coming of sound, though Chaplin had no intention of participating in this revolution.

Therefore, City Lights was going to be a big deal indeed. Chaplin worked slowly and carefully on every film and this one was far from an exception. A long and funny scene was discovered in Chaplin’s vault years after his death which was obviously intended to be City Lights opening. However, it was not quite as good as what Chaplin decided to go with in opening the film and bringing on his immortal Little Tramp.

A fancy crowd is gathered in an outside urban location to unveil a monument to… well, something or other (not stated, completely unimportant). The various dignitaries, male and female, all get up to say their pompous pieces (and Chaplin wittily uses trumpet sounds on the soundtrack to mock the pointless speeches).

While all this is going on, a very large monument, covered by a large canvas tarp, is present in the background. The tarp is pulled away by the ropes attached to it to reveal three statuary figures, with the Tramp calmly sleeping in the lap of one of them. He awakens to the socially awkward situation, not that he was ever unduly concerned with social propriety.

As he moves among the figures to try and forge an exit, the figures join with him to mock the crowd (with one figure seeming to help the Tramp thumb his nose at the mob). This is the essence of the Tramp: polite and well behaved in some way, wild, free, and socially unconventional in others. This remained Chaplin’s finest entrance.

8. Malcolm McDowall in A Clockwork Orange (1971)

Stanley Kubrick was a total film maker and his favorite star always seemed to be his camera. However, there were times in his cinema where the actor could not be denied. Peter Sellers was surely an example of this in 1964’s Dr. Strangelove, but perhaps the ultimate example of an actor dominating a Kubrick film was Malcolm McDowell as Alex in the always controversial A Clockwork Orange.

McDowell was a new comer to film at the time after starting a promising career in the theater and making a splash with his lead performance as a rebellious youth in an earlier controversial British film, Lindsey Anderson’s 1969 classic If…

This film, set in what was then the future (now the distant past), presents an alternative version of what may have been if the sex and violence trends of the late 60s and early 70s had continued unabated (and, to some, they did, but just didn’t look like this film’s version of it all).

Alex is the leader of a really punkish gang (droogs in the vernacular of the film’s world). Clad in white spandex outfits with cod-pieces, accentuated by black belts with pouches for accoutrements and bowlers, the gang is an outlandish sight indeed.

Alex is the most extreme of them all with his handsome face highlighted by pronounced false eyelashes. The film opens with a long, long lingering shot of Alex, staring at the camera as it slowly pulls back to reveal him in the modernistic “milk bar”, his unwholesome natural habitat. In this scene-setting moment, the viewer knows that a high-octane force will be leading this film.