10. Eraserhead – David Lynch (1977)

This is the film that created a cinematic auteur, and it is a surrealist body horror film that later gained a reputation as a midnight movie. The film was very hard to finance, and Lynch could only pull it off through the help of Jack Fisk and his wife Sissy Spacek.

Somehow, this is the scariest Lynch film, as the low budget nature of the effects give a grungy intensity to the oneiric sequences. Decapitation, drones, blues, monstrous rabbits, and creepy ladies populate the big gothic nightmare of the film, which echoes the great Jean Epstein’s “Fall of the House of Usher”.

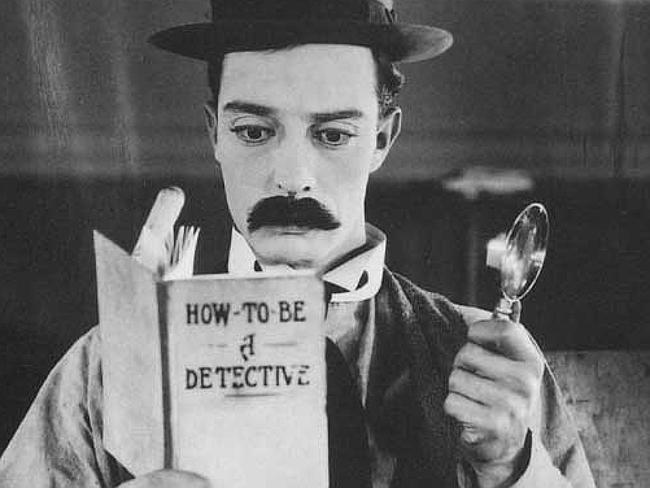

9. Sherlock Jr – Buster Keaton (1924)

In its first 40 years of existence, cinema retained a quality of absolute magic and dream that it will never recover, with the evolution of visual communication, television, and home video. Influenced by avant-garde literature of the time and a love for cinema, Buster Keaton created a dream sequence that was also one of the early examples of meta-cinema.

While working as a projectionist, he experiences a body separation as he is transformed in an aura and enters the films he is projecting. From there, he employs some of the greatest cuts in the history of cinema as he jumps from one setting to another – a house, a garden, a mountain, a street, lions that chase him, a desert, a rock in the sea, a winter landscape. Keaton used the dream sequence to curve the cinematic material to express all his unruly, chaotic power, all with the help of his comedic class.

8. Brazil – Terry Gilliam (1984)

Terry Gilliam’s love for the 1930s, for Lewis Carroll and Don Quixote, shines through in the dream sequences of his greatest film, “Brazil”. Gilliam mixes flight sequences of great magic and bright colors with giant structures typical of postmodern and cyberpunk sensibilities, surreal imagery inspired by Gustave Dorè, musicals and Japanese visual arts in creating the dream moments of his film.

These dreams are not just moments of liberation, but also moments of deeply black comedy in depicting the desperate escapism of the protagonist and the devastating effects of modern life on him.

7. The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser – Werner Herzog (1974)

If we were, like Kaspar Hauser, separated from the world, all would look like a dream. However, Hauser is endowed with the power of reaching ecstatic visionary truths, the thing that Herzog looks for in his films. The dream sequence in the desert is one of the best sequences in the history of cinema. It is very difficult to describe, but the exotic weirdness that Herzog creates through the warped narration, the saturated image, and the flute playing is impossible to recreate; it is indeed an ecstatic truth.

The film also has another sequence that is on the same level of mystical truth – the sequence with the valley of temples in Myanmar, although this sequence is very brief. These are not only dreams, not in the way they are presented; in this case, the dream sequence has the function of a Platonic myth, a poetic way of reaching a deeper truth that escapes rational analysis.

6. The Phantom Carriage – Victor Sjostrom (1921)

“The Phantom Carriage” is an important film in that it influenced Ingmar Bergman, used special effects that were advanced for the time, put Swedish cinema at the center of critical attention, made Sjostrom a star director, and is an essential film in the canon of gothic horror.

Sjostrom used double exposure to create the famous dream sequences with the ghosts and the carriage of Death itself, characterizing phantoms and Death as the persistence of time and memory. Sjostrom’s film can stand next to great cinematic works of the same age like Erich Von Stroheim’s films, and next to great literature like the writings of Charles Dickens, Dostoevsky, and Edgar Allan Poe.

5. Mulholland Dr. – David Lynch (2001)

What dream? That would be the best question when analyzing dreams in David Lynch films, where reality slips into dreams and dreams fade back into reality with a single editing dissolve, with a single cut, a single camera movement or saturation of the image.

Three sequences make the film legendary; the sequence at the diner, with the droning sound that rises from the abyss of the subconscious until the monstrous figure shows up, terrifying the character and the audience; the sequence at the club Silencio, where a slow Spanish version of Roy Orbison’s “Crying” moves the characters and the audience to tears; and the sequence where the two little old people emerge from the blackness and then erupt into the psyche of Naomi Watts, in a cacophony of screams, noises, and panic, which leads to a suicidal conclusion.

“Mulholland Dr.” is peak of Lynch’s cinematic sensibility, and even though it is not his best film, it’s a sublimation of his style, in which the dreamy glimmer of Los Angeles is present in the most photorealistic sequences and in the most adventurous blackened nightmares.

4. Spellbound – Alfred Hitchcock (1945)

The fault is not in our stars, but in ourselves. This is Shakespeare’s quote that opens the film, a film which was meant to be a tribute to psychoanalysis and its virtues. The sequence that made this film unforgettable was the dream sequence, which was designed by the great surrealist artist Salvador Dalì, and is full of psychoanalytic symbols that retrace the elements to gain an understanding of the memory and the trauma of the character.

A Lacanian reading of the dream interprets the dream as the manifestation of the troubled gaze of the director and the way he sees his characters in symbolist terms. The dream is also the result of a sexual fantasy. Eyes and knives both coexist in representing the Oedipus complex and the phallic symbolism of Freudian theory.

3. Un Chien Andalou – Luis Bunuel (1929)

This is the film that defined the surrealist movement. “Un Chien Andalou” uses Freudian free association and dream logic; both are techniques that were becoming popular at the time in other forms of art, like literature and painting, and utilizes it in a cinematically in the best way possible.

The associations include three of the greatest sequences of all time – the hand with the insects, the horse head, and the scene with the razor – which is the most famous free association scene in the history of cinema, when a razor becomes a cloud in front of the moon and then becomes a razor again, and the moon becomes an eye, and the razor cuts the eye.

2. Wild Strawberries – Ingmar Bergman (1957)

“I dreamed that during the morning walk, I lost my way among empty streets with ruined houses.” Bergman filmed his dream sequences with the adamantine and monumental bleakness and austerity of his filmmaking sensibility.

In the film, nightmares, dreams, and recollections of other kinds are all part of the process of evaluating life and approaching death.

1. 8½ – Federico Fellini (1963)

This is meta-cinema at its finest. Fellini put all of his obsessions in this tale of a struggling director who is haunted by the visions of a woman about whom he wants to make films. Fellini’s intention was investigating the nature of films as dreams, but also portray the universe that surround him.

In the opening sequence, he is able to create a dream sequence in which he acutely observes the middle class urban landscape of the 1960s, and mixes it with visions that begin as slightly erotic and then transform in a dazzling light sequence or unmatched weightlessness. The harem dream sequence is the other standout sequence, with a mixture of eroticism, grotesquery, and social commentary.

Author Bio: Gabriele is an Italian film student studying in Scotland. He is an experimental and arthouse cinema enthusiasta and a believer in the crucial importance of freedom of artistic expression.