The 1950s are considered the Golden Age of Japanese cinema. The aftermath of World War II and particularly the atomic bomb, and the subsequent American occupation left the country scarred, but filled with inspiration and eagerness to start over.

As the Japanese economy started to rise once more, five major studios emerged that shaped Japanese cinema. Toho, Daiei, Shochiku, Nikkatsu, and Toei hired the most gifted artists of the era and financed their movies, in a tactic that resulted in a plethora of masterpieces. In the process, they also made a lot of money, as the people, having their pockets filled due to the rapid economical growth, filled the cinemas.

At the same time, the prowess of Japanese cinema became an international phenomenon, with films winning awards at Venice, Cannes, even the Oscars. Filmmakers like Akira Kurosawa, Kenji Mizoguchi, Yasujiro Ozu, and Masaki Kobayashi were acknowledged as Grand Masters, with their films of this decade still considered among the best of all time.

Lastly, during this decade, the first color films were presented and a new genre was established that would later become one of the most popular in the country. It was named “Kaiju”, and its most renowned character was Godzilla.

These are the 20 best productions of the decade. I have made an effort to place the titles in order of quality, but due to the number of masterpieces included, the order could easily be different.

Note that although the last part of “The Human Condition” trilogy was released in 1961, it is included here, since I regard the trilogy as a single film.

20. Carmen Comes Home (Keisuke Kinoshita, 1951)

This musical comedy was the first Japanese film shot entirely in color, and celebrated Shochiku’s 30 years of operation.

It was filmed using Fujicolor, and the company’s technicians advised that the still experimental process would work best in outdoor locations. Having that in mind, Keisuke Kinoshita wrote a script about Lily Carmen, a star of Tokyo striptease shows, who returns to her peaceful village with her friend, Maya. The two girls cause quite a stir with their scandalous outfits and their singing and dancing, entertaining the village, but causing embarrassment to Carmen’s father.

The film is actually an easygoing musical comedy, which takes as much advantage as it can from Hideko Takamine’s popularity and looks. Furthermore, Kinoshita satirized the influence of American culture in postwar Japan, in a movie that eventually became one of the most loved in his filmography.

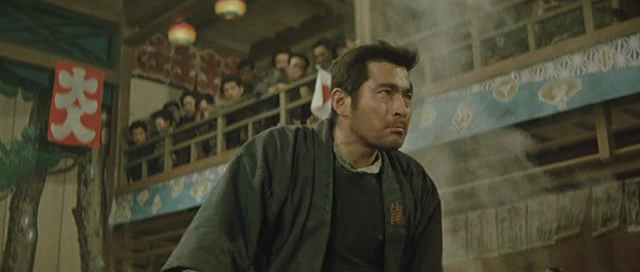

19. Rickshaw Man (Hiroshi Inagaki, 1958)

Remade from a 1943 film with the same name, “Rickshaw Man” became quite popular in the West, and even won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival.

Matsu is a poor rickshaw driver, whose luck and life changes when he takes an injured boy home. The boy turns out to be the son of an upper class family, the Yoshiokas, with the father, Captain Yoshioka, eventually hiring Matsu to take the boy to school and back.

When the captain dies, his wife, Yoshiko, raises the boy with the help of Matsu. Inevitably, the two of them become closer, but they both know that their relationship cannot happen due to their class difference.

The film has a tragic ending, but is quite easygoing, as it focuses on Matsu’s antics and the unrequited love between him and Yoshiko. All of the characters are likeable and even the tragic ending leaves a sweet aftertaste, since it exemplifies Matsu’s characters.

Inagaki drew a great performance from Toshiro Mifune as Matsu, in a very different role than the ones for which he is still hailed. In that fashion, Mifune proved his range as an actor.

18. Godzilla (Ishiro Honda, 1954)

The “kaiju” genre started with this film, which signaled the first appearance of one of the most iconic characters of global cinema: Godzilla, a 400-foot dinosaur with distinct Tyrannosaurus Rex features and characteristics.

Godzilla is awakened by the explosion of an atomic bomb, and emerges from the sea to wreak havoc, initially on a few fishing villages and then to Tokyo. The monster seems to be drawn in by electricity, and is not particularly interested in humans, who are killed in scores as Godzilla passes through the city. The military seems unable to face him and the only hope lies with an invention from a scientist.

The film had a huge impact on Japanese audiences, who were largely intrigued by both the evident exploitation of recent memories of the A-bomb, and the concept of kaiju, which was unprecedented in Japan. The film entailed great special effects by Eiji Tsuburaya, who created magnificent destruction scenes using manufactured models instead of computer graphics, and an all-star cast headed by Takashi Shimura.

Furthermore, the concept of the scientist who sacrifices himself found great appeal with Japanese audiences, with the concept of the Kamikaze in World War II being equally recent with that of the bomb.

17. The Sound of the Mountain (Mikio Naruse, 1954)

This film is adapted from the homonymous novel by Nobel Prize winning author Yasunari Kawabata, and is Mikio Naruse’s favorite work.

Shuichi, a successful entrepreneur, lives with his wife, Kikuko, and his parents, Shingo and Yasuko. Kikuko is an exemplary wife and takes care of her husband’s parents, but Shuichi has a mistress. When Shingo learns this, he visits the girl, and is surprised to learn that she is pregnant and plans to keep the baby.

This event, along with Kikuko’s pregnancy and his daughter’s failed marriage, who has also forced her to move into the house with her two children, makes Shingo take a closer look at his role as a father and patriarch.

Narrated from the perspective of Shingo, the film functions as a meditation on aging, while stressing the immorality of the post-war generation. Shingo blames himself for his children’s failed marriages and he feels regret for his past acts. This guilt provokes him to think about life, love, and companionship.

As Naruse revisits the themes previously expressed on “Repast”, he directs a tribute film, with this tendency even extending to the sets and locations, which were designed to look like Kawabata’s own home and neighborhood.

16. Fires on the Plain (Kon Ichikawa, 1959)

Based on the novel “Nobi” by Shohei Ooka, “Fires on the Plain” was not well received during its release time, as it was considered overly violent and bleak. However, in the following decades, its realism and its clear anti-war message were appreciated, and the film got the position it deserved among the masterpieces of the decade.

The story takes place in the Philippines during the end of World War II, when the Allied Forces were in the process of liberating the island from Japanese occupation. Tamura is a tubercular private who is kicked out of his company, as he is considered a burden.

This event initiates Tamura’s odyssey into the inhumane, as he first encounters a couple trying to retrieve their hidden salt, eventually killing the wife, and finally ending up with a group of soldiers that have resorted to hideous acts in order to survive.

Kon Ichikawa felt that he had to speak about the horrors of war, and he did so in the most graphic fashion, relentlessly portraying images like wounds oozing blood, teeth dropping from the protagonist, and piled-up dead bodies. However, his most grotesque images come from the cannibalism from which the soldiers have resorted.

There are moments of compassion among these hellish depictions, and Kon even managed to include dark and ironic humor, as in the scene where a dying soldier thanks Tamura by saying “I won’t forget your kindness as long as I live.”

15. Repast (Mikio Naruse, 1951)

“Repast” is the first of Naruse’s adaptations of the novels by Fumiko Hayashi, and is credited with reviving the shomin-geki (working class) genre of the ‘50s era.

Married for five years but without any children, Hatsunosuke and Michiyo live an uneventful life in Osaka, with him ignoring her, and her being discontent by both his behavior and by domestic work. Their routine is disrupted by the appearance of Hatsunosuke’s niece, Satoko. One night, Michiyo finds her and her husband lying on the floor alone and decides to leave, and takes Satoko with her to Tokyo, where they both grew up.

In her family’s house, she enjoys the food and the rest, although her mother constantly reminds her of her duties. Eventually, Hatsunosuke comes to find her.

Naruse directs a film about the discontents of everyday life, particularly from the woman’s perspective. His take on the subject of marriage comes from a phrase Michiyo utters, that she wants someone to take care of her rather than participate in an equal marriage.

The film has plenty of dialogue and almost no action, and in that fashion, it focuses heavily on the actors’ performances, a trait that becomes even more important, considering that Naruse usually gave more creative freedom to his actors. As the cast features some of the greatest actors of the era, including Ken Uehara, Kinuyo Tanaka, Hideko Takamine, and Setsuko Hara, the result of his tactics were remarkable.