7. Rashomon (Akira Kurosawa, 1950)

“Rashomon” is considered the film that introduced Japanese cinema to the global stage, with Kurosawa netting an Honorary Award from the 24th Oscars and the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, among a plethora of others. Currently, it is hailed as one of the greatest films ever made.

A villager and a priest find solace from the rain under the Rashomon gate and soon after, another passerby joins them. Waiting for the hurricane to pass, they busy themselves by discussing a heinous crime that occurred in the nearby forest, where a samurai was tortured to death and his wife was raped. The main suspect is a notorious criminal.

The three men try to reach the truth, using their memories of the testimonies of the woodcutter who discovered the body, as well as those from the accused Tajomaru, the raped widow, and the deceased’s spirit through a medium.

Kurosawa directs a movie that revolves around the way humans perceive and interpret reality by using a number of unprecedented techniques, as with the various characters providing alternative and even contradictory versions of the same incident.

Lastly, the film presented a direct shot of the sun, an action that was considered taboo up to that point, in a sequence that exemplifies the wonderful cinematography of Kazuo Miyagawa.

6. Sansho the Bailiff (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1956)

One of the greatest films of both Kenji Mizoguchi and Japanese cinema, “Sansho the Bailiff” is a true audio-visual masterpiece.

The script revolves around a brother and a sister, whose family has been torn apart by a virtuous governor, and several years later by an evil priestess. The children eventually end up in a slave camp, where Sansho the Bailiff is in charge.

Mizoguchi deals with the theme of vengeance, as he explores the inhumane nature of many individuals. In a deeper layer, through symbolism, he also makes a harsh critique of the Japanese feudal system.

“Sansho the Bailiff” also features elaborate cinematography, which transcends the technical aspect by depicting images filled with symbolism and meaning, with the help of Kazuo Miyagawa, Mizoguchi’s regular collaborator.

As Mizoguchi’s style was deeply inspired by the composition and mood of traditional Japanese paintings, the motion in the film tends to appear vertically instead of horizontally, and frequently, even diagonally. The film also features the distinct, artful long shots of Mizoguchi, which aim at placing the characters within their symbolic environment.

The symbolism is also present in the movement, as movement to the left suggests backward in time, and to the right, forward. Upward movement suggests hope, and downward the opposite.

5. Ugetsu Monogatari (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1953)

This film is probably Kenji Mizoguchi’s most celebrated, and is considered a definitive part of the Golden Age of Japanese films.

In 16th century Japan, two ambitious peasants want to change their fate. Genjuro, a potter, dreams of going to Kyoto to sell his merchandise and Tobei, his son-in-law, dreams of becoming a samurai.

However, due to civil war, their village is completely annihilated by soldiers, but the two couples manage to survive. As they leave their village, they are met by a boat in Lake Biwa, whose sole passenger warns them to go back, before he dies. The men decide to send their wives back and proceed to sell Genjuro’s merchandise in the market. They sell well and Tobei takes his share and tries to fulfill his dream.

Meanwhile, Lady Wakasa, a noblewoman, shows interest in Genjuro’s products and invites him into her home.

Mizoguchi directs a film that ignores every norm of cinema, creating in the process a poetic and anti-realistic spectacle, as its seemingly melodramatic nature is affected by the world of spirits.

Furthermore, some of his most renowned scenes are included here, with the help of cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa.

The first of those scenes occurs in the very beginning of the film, as the camera pans across the landscape, in the fashion of traditional Japanese scroll painting, in one of Mizoguchi’s most distinct characteristics.

The second and most famous one is the scene in the lake with the boatman. The scene was partly shot in a tank with studio backdrops, but the cinematography and motion is so perfectly implemented that the scene looks 100 percent natural.

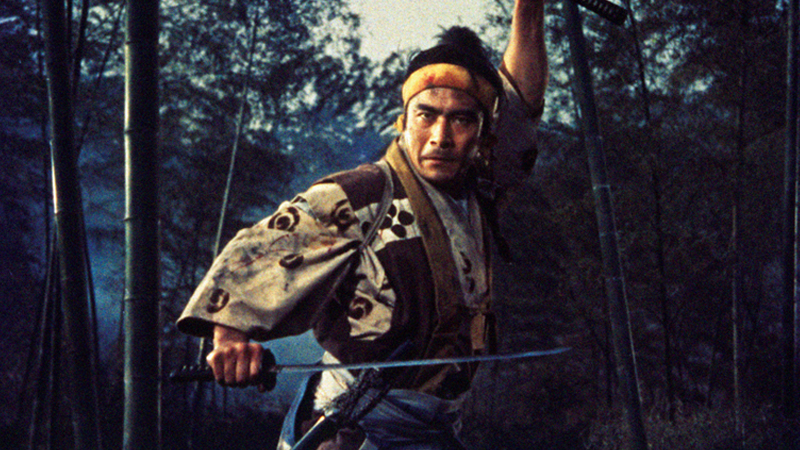

4. Samurai Trilogy (Hiroshi Inagaki, 1954, 1955, 1956)

The trilogy is based on the novel “Musashi” by Eiji Yoshikawa, which follows the renowned Japanese swordsman’s growth from an immature youth to a wise samurai. The first part won the 1955 Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, and the trilogy is considered one of the most influential in world cinema.

Toshiro Mifune is astonishing as Musashi in all three films, in one of his works that established him as one of the biggest actors of the era in Japan. Koji Tsuruta, who plays his archrival, Sasaki Kojiro, is also great, with their duel at the end of the third part being the highlight of the trilogy.

The battles are all astonishing, in realistic fashion, as they benefit the most by Yoshio Sugino’s action choreography, but the trilogy is much more than an action feature. It deals with Musashi’s self-discovery, which eventually led him to become a philosopher, as he wrote “The Book of the Five Rings”.

Furthermore, the trilogy is a testament of both Japanese culture and psychology.

3. Seven Samurai (Akira Kurosawa, 1954)

Akira Kurosawa’s masterpiece is one of the most influential films of all time.

The black and white movie revolves around seven wandering samurai who are hired to defend the seedy inhabitants of a small village, who are threatened by bandits, while their payment is simply rice.

Kurosawa entailed all the aesthetics of the Golden Age of Japanese cinema, including form, pace, character depiction, and magnificently choreographed action to present a film that excels in all departments.

Along with his cinematographer, Asakazu Nakai, he managed to portray images of astonishing detail and elaborateness, which are chiefly evident in the action sequences, as Kurosawa guides the camera splendidly.

The magnificent cinematography finds its apogee in the ending sequence, where the samurai fight the bandit. The use of a telephoto lens, along with the quick cutting, stresses the chaotic and claustrophobic feeling the scene emits.

“Seven Samurai” became the basis for many films, with John Sturges’ “The Magnificent Seven” being a direct adaptation.

2. The Human Condition Trilogy (Masaki Kobayashi, 1959, 1959, 1961)

The trilogy is based on the six-volume, autobiographical novel by Junpei Gomikawa, published from 1956 to 1958. It is considered one of the masterpieces of world cinema and established Masaki Kobayashi as one of the most important Japanese directors of the generation.

The film follows the Sisyphean life of Kaji, a pacifist and socialist who finds himself repeatedly crushed by the totalitarian Japanese regime of the World War II era, as he tries to avoid becoming an actual soldier.

His story will bring him from a Manchurian POW camp to the front, and finally back to Manchuria, as he tries to return to his wife in the final installment.

Kobayashi directs a film about existential despair and the dilemma of a man who rejects existing society, but has to remain with it. His struggle is a series of truly heroic acts, as he tries to avoid being tainted and even corrupted by the system.

The film is hailed for its realism, with cinematographer Yoshio Miyajima doing an excellent job in this aspect.

As Kaji, Tatsuya Nakadai gives an astonishing performance in his first leading role, in a work that established him as one of the greatest Japanese actors of the era.

1. Tokyo Story (Yasujiro Ozu, 1953)

Yasujiro Ozu’s magnum opus is considered one of the most genuine Japanese films of all time, and in 2012, filmmakers voted it the best film of all time, replacing “Citizen Kane” at the top of the “Sight & Sound” directors’ poll.

Set in Tokyo eight years after the end of World War II, the film revolves around a visit an elderly couple pays to their children, who live with their families in the ever-growing metropolis. Their children, however, do not seem to want to associate much with them, and eventually abandon them at an inn at a tourist resort.

Ozu directs a film that has an evident predilection toward the traditional values of Japanese society, in contrast to the new values resulting from the raging modernization of Japan in the decades after the war. In that fashion, the elderly couple seems happy and filled with love, compared to their kids’ families that seem tortured by issues caused by modern society.

However, Ozu avoided melodrama by focusing on images rather than dialogue, in order to express his view. There are three main characteristics of Ozu’s cinematography. The first is the placement of the camera three feet above the floor (the eye level of a Japanese person seated on a tatami mat), in order to eliminate space and make a two-dimensional space.

The purpose of this technique is to make the audience feel as if they are actually participating in the film, thus becoming more receptive to the characters.

The second is that he almost never moves the camera, since every shot is intended to have a perfect composition of its own. In fact, in “Tokyo Story”, it only moves once. The third is that, during the dialogues, Atsuta places his camera between the people conversing, to make the audience feel like they are standing in the middle of a conversation.

All of these techniques are implemented with this film, in the most wonderful fashion.

Author Bio: Panos Kotzathanasis is a film critic who focuses on the cinema of East Asia. He enjoys films from all genres, although he is a big fan of exploitation. You can follow him on Facebook or Twitter.