14. Bushido, Samurai Saga (Tadashi Imai, 1963)

The film is one of the most renowned in Tadashi Imai’s filmography, particularly because it won the Golden Bear at the 13th Berlin International Film Festival.

The film begins in the present with Iikura, a man saddened and perplexed by the attempted suicide of the woman who loves him. His sentiments lead him to examine the chronicles of his ancestors, who belonged to the samurai caste for centuries. The story then presents the lives of seven different samurai of the bloodline.

Imai casts a distinctly anti-samurai and anti-militaristic visage upon the institution of the samurai, and particularly the Bushido, the code by which they lived. Through several generations, he shows how this code destroyed the lives of every man in the family who followed it, up to the present day, where Bushido manifests as obedience to authority. This authority, however, takes away much more than it offers.

Imai used plenty of graphic violence in the film, not in exploitation fashion, but rather as a medium for criticizing samurai and the whole caste system.

Kinnosuke Nakamura is the uncontested star of the film, as he plays seven roles, of all the samurai in the bloodline. His performance is magnificent in a rather difficult effort, since the characters he plays differ radically.

13. Branded to Kill (Seijun Suzuki, 1967)

The number three professional hit man in the world is a very peculiar man with a fetish for boiled rice and an obsession to become number one. In order to accomplish this, he takes on a series of increasingly deranged assignments. In one of them, he meets a mysterious woman who he falls in love with, in a relationship that eventually brings him against other contract killers.

This preposterous black-and-white film, which lingers somewhere between metaphysical thriller and noir, was the reason Suzuki clashed with and eventually left Nikkatsu Studios, particularly because he ignored and even mocked all the gangster film conventions. His ingenuity, however, becomes evident once more through a number of visual and thematic surprises incorporated in the film.

Currently, it is considered a cult classic by fans of the category from all over the world.

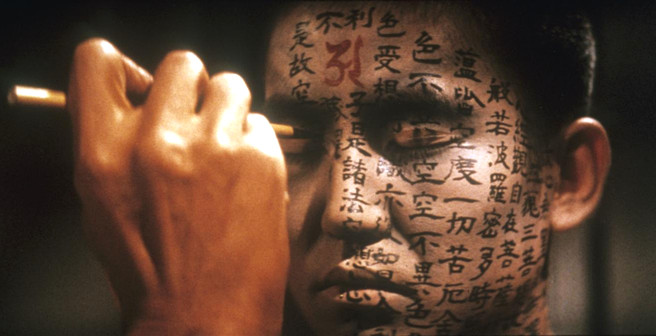

12. Kwaidan (Masaki Kobayashi, 1964)

Masaki Kobayashi is one of the most important Japanese post-war filmmakers, with his prowess becoming quite visible in this film, which was nominated for an Oscar and won the Jury Special Award in Cannes.

“Kwaidan” features four horror stories, based on the homonymous book by Yakumo Koizumi. All of the segments deal with the relationship of everyday people with the supernatural world, particularly ghosts, and include a plot twist at the end.

The collection stands apart due to its wonderful aesthetics, which include sentiment and a dream-like essence. Furthermore, Kobayashi deals with interracial relationships, justice, and time through the horror produced from the supernatural.

11. Funeral Parade of Roses (Toshio Matsumoto, 1969)

Toshio Matsumoto is one of the most renowned artists and academics in Japan, and aside from being one of the most prominent members of the Japanese New Wave in film as well as an accomplished photographer, he is also a professor and Dean of Arts at the Kyoto University of Art and Design, and the President of the Japan Society of Image Arts and Sciences. “Funeral Parade of Roses” is his debut and his most distinct film.

Trying to survive her traumatic past, a young transvestite strikes up an affair with an older man, who is also the owner of the nightclub where she works. However, she does not know that he is the one holding the key to the tragic destiny she is meant to face.

The film is a masterful combination of avant-garde and exploitation aesthetics that result in a collage of dialogues, memories, interviews, thoughts, lyrics, and extracts presented in a psychedelically vague narration, rather than a “regular” film.

Furthermore, Matsumoto managed to demolish almost every taboo existing at the time: nudity, sex, drugs, but most of all, the unfaltering depiction of the Japanese gay society through the eyes of a transvestite, which made the majority of the other films of the movement seem almost conservative.

10. Kuroneko (Kaneto Shindo, 1968)

“Kuroneko” is often compared to “Onibaba”, due to the setting of a mother and a daughter-in-law waiting for the son of the house, and the main theme of revenge.

During a civil war in Japan’s Heian period, a woman and her daughter are raped and murdered by soldiers. After the end of the war, samurai are continuously found decapitated near the place where the women used to live. The governor sends a newly appointed samurai to discover the murderer, who seems to be a ghost. The samurai meets the two women, along with a powerful demon.

Kaneto Shindo adapted the vampiric myth into Japanese tradition, which was already filled with stories about demons, ghosts, and spirits. The genuine terror combined with a sense of extreme eroticism, the tension produced by the contrast of the black-and-white cinematography, and the splendidly choreographed aerial battles of the characters, establish “Kuroneko” as one of the most artful cult films of all time.

Additionally, “Kuroneko” is considered one of the masterpieces of the J-horror genre.

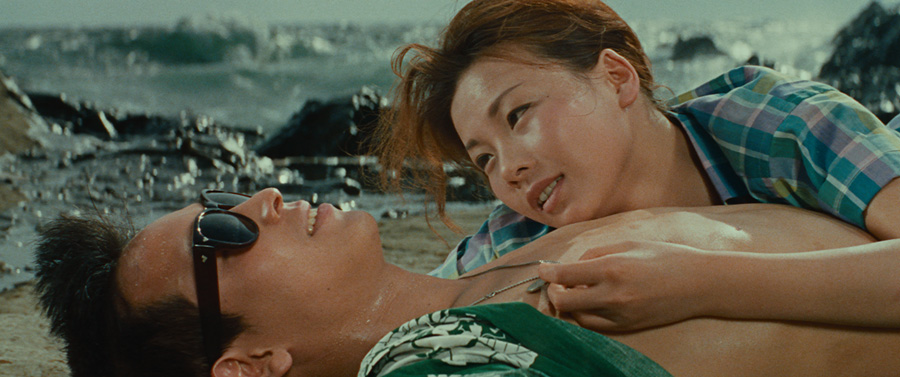

9. Cruel Story of Youth (Nagisa Oshima, 1960)

Nagisa Oshima’s second feature film is a prime example of the Japanese New Wave, as it focuses on adolescent delinquency, the sexual revolution, and the failures of the post-war generation. Furthermore, it was his first commercial success and the one that introduced him to the rest of the world.

Makoto, a high school student, has the habit, along with her friends, to ask for car rides from middle-aged men. During one of these rides, a lecherous individual tries to rape her; however, a university student named Kiyoshi saves her by beating the assaulter, and shortly after, the two of them begin a romantic relationship.

Nevertheless, the affair is onerous from beginning, chiefly due to Kiyoshi’s cruelty, which results in torturing her and utilizing practices that today would be easily characterized as date rape. However, the girl eventually succumbs to him and the two fall in love. Moreover, they decide to leave together in a shack, despite the strong objections by her siblings, especially her sister, who had a similar affair when she was young that ended abruptly, and believes that the same will happen with Makoto.

Oshima, who was only 28 at the time, directed a movie that generated controversy due to the depiction of adolescent criminals, exploitation themes, and many sex scenes, although the latter are not graphically depicted.

The movie’s social background initiates by depicting an age of innocence, when girls could hitchhike without being afraid. However, he quickly proves that the sense of security is an illusion and that the world is cruel, inhabited by individuals who are rarely kindhearted and compassionate. On the contrary, his main characters are all ready to take advantage of the people around them, thus transforming constantly from victims to culprits and vice versa. Evidently, innocence is long lost in postwar Japan.

8. Onibaba (Kaneto Shindo, 1964, Japan)

In 14th century Japan, a man is forced to enlist the army, leaving his wife and his mother alone in their house in the swamp. In order to survive, the women ambush passing soldiers, killing them and subsequently selling their belongings to a greedy merchant. Nevertheless, the wife begins an affair with a deserter, enraging her mother-in-law who no longer trusts her.

Additionally, the mother tends to wear a mask stolen from a butchered samurai. However, inside the mask resides a demon that eventually takes over.

Kaneto Shindo shoots the film exclusively in a swamp, where the protagonists live their own hell. Water, canes, and mud constitute an environment that, when combined with the black-and-white cinematography and the long, internal pauses, results in a silent nightmare. Shindo presents a movie concerning the worse of human instincts and an apparent message: the sole hell is the one where human beings live.

The violence, the sex scenes, and the concept in general were unheard of in the 1960s. Nevertheless, “Onibaba” was a commercial success and one of the foremost renowned titles of the prolific director.