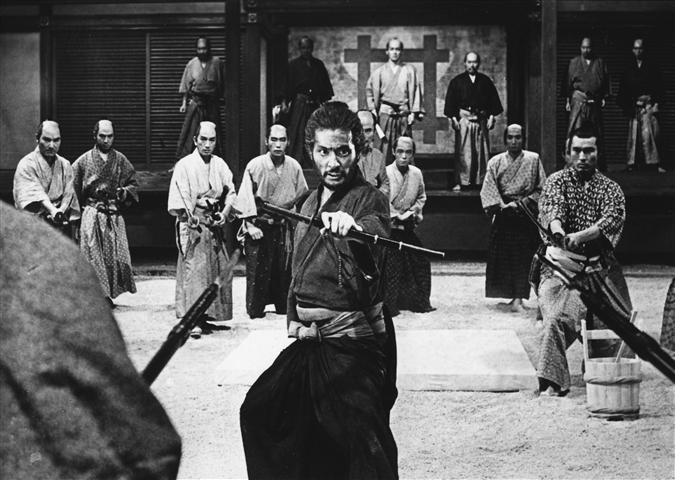

7. The Sword of Doom (Kihachi Okamoto, 1966)

Based on the homonymous, historical novel by Kaizan Nakazato, “The Sword of Doom” was supposed to be the first part of a series of films that never actually materialized. However, in spite of this, and in spite of its abrupt ending, it remains one of the best jidai-geki films.

The film tells the story of a cruel samurai named Ryunosuke, an expert swordsman who seems to enjoy killing other samurai. Before one of his duels, he is approached by Hama, the wife of his opponent, who begs him not to humiliate her husband. In return, he asks her to sleep with him. When her husband learns of this fact, he is infuriated, but the duel ends with a devastating win for Ryunosuke.

Ryunosuke then allows Hama to live with him. As his financial situation is quite bad, he joins a gang of outlaws.

Kihachi Okamoto paints a very dark image of the noble concept of the samurai, as Ryunosuke is actually a violent sociopath who does not hesitate to kill and take advantage of anyone that comes along his way. However, Okamoto’s perspective toward him seems to be one of admiration.

The film features magnificent fight sequences, and Tatsuya Nakadai is sublime as nihilistic anti-hero Ryunosuke.

6. When a Woman Ascends the Stairs (Mikio Naruse, 1960)

Mikio Naruse’s masterpiece is an ode to realism and minimalism, as well as a study of the role of women in the Japanese society of the 60s, stripped from any kind of disillusions.

Every afternoon, young widow Keiko leaves her small apartment to attend a bar in Ginza, where she entertains entrepreneurs after they finish work. Due to her kind nature, the younger girls at the bar call her “mama”, acknowledging her finesse and beauty as the apogee of their profession. Kenichi, the man in charge of the bar, has feelings for her, but he keeps them hidden. As time changes, girls from the other bars resort in unethical tactics to draw in clients, but Keiko refuses.

Naruse creates a disillusioned, melancholic, and deeply tender portrait of dignity and patience. Using the repeated sequence of Keiko ascending the stairs to the bar, he depicts the transition from her real life to the professional one, which demands a radical transformation. Naruse’s trademark pessimism is not missing; Keiko seems to find obstacles any time she tries to achieve freedom.

Hideko Takamine is magnificent as Keiko, elaborately depicting a complex character who actually lives two radically different lives.

5. Death By Hanging (Nagisa Oshima, 1968)

This film is based on a peculiar case that occurred in 1958, when a Korean young man killed two Japanese students and not only confessed his crimes, but also wrote about them in detail. Furthermore, his writings are published in a collection that became as famous as he did.

Taking the particular case as a base, Nagisa Osima expressed his ideas regarding the death sentence, crime and punishment, Japanese racism towards Koreans, imperialism, and a series of existential matters.

The black-and-white film begins like a documentary, with Oshima presenting in detail the place where executions were held and the procedure itself. However, R, who identifies with the Korean perpetrator, does not die in the procedure, and the bystanders (police officers, priests, and politicians) remain perplexed as to whether he is alive or dead.

Osima makes a harsh comment regarding the authorities, as he presents them as caricatures, and considers their obsession with crime more intense than that of any criminal.

In terms of style, Osima’s previous realism is nowhere to be found, with the film functioning as a theatrical play and the expressionism being the dominant element.

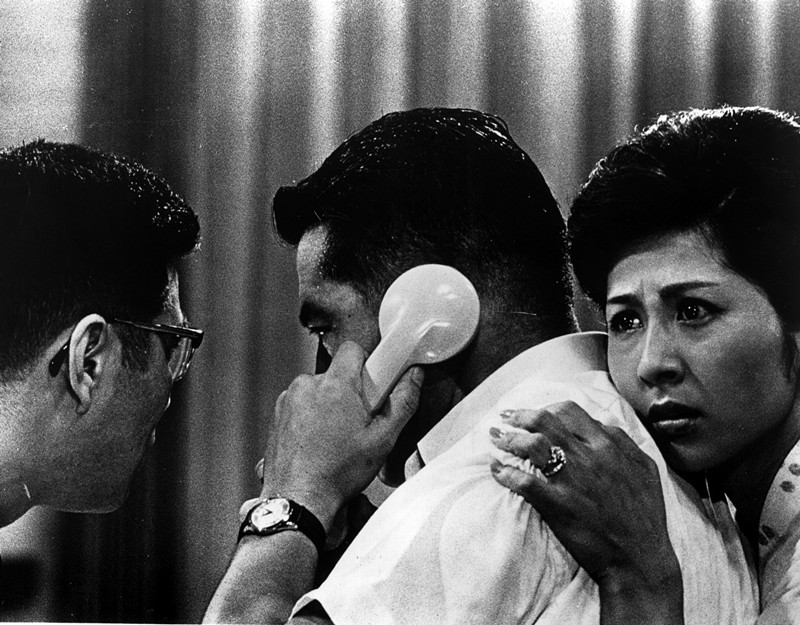

4. High and Low (Akira Kurosawa, 1963)

Kingo Gondo, a wealthy executive, is trying to take over a shoe company. During his efforts, he is informed that his son has been kidnapped, with the ransom money amounting to the sum he accumulated to buy the company. As he is about to pay, he discovers that it was not his child that was kidnapped, but his chauffeur’s. Godo now has a dilemma of whether to pay the money or not.

The film is split into two parts, with the second one portraying, in documentary style, the police procedures regarding the solving of the crime.

Behind the interesting plot, the noir, and the documentary aesthetics, Akira Kurosawa hides a number of messages regarding social position, the sympathy for the lives of others, prejudice, and self-sacrifice.

Toshiro Mifune as Kingo Gondo and Tatsuya Nakadai as the police chief are both magnificent in their roles.

3. Harakiri (Masaki Kobayashi, 1962)

In feudal Japan in the 17th century, the ongoing peace has brought the samurai caste to its knees, as they have no work and no money. In their despair to find a noble way of dying, many of them resort to requesting permission from their lords to commit hara-kiri.

Chijiiwa Motome arrives in front of Saito, the Daimyo’s senior counselor, and states that he wants to commit seppuku. As this request is part of a series of identical, “fake” requests, the three most senior samurai of the clan persuade Saito to order Motome to fulfill his request. However, as Motome’s request was not real, he did not carry with him a katana, but rather a bamboo blade. This fact enrages all of the bystanders and finally, Saito orders him to proceed with the specific sword.

Masaki Kobayashi shot the aforementioned scene in the most grotesque fashion, as the fact that the sword is wooden makes the act slower and more agonizingly painful as Motome tries to desperately to penetrate his abdomen with the wooden blade. Furthermore, the order is deeply humiliating, further heightening the shock the scene produces.

The film also features a number of magnificent action scenes, but Kobayashi’s actual purpose was to depict the futility of the ancient ritual, and at the same time to portray samurai, who are still considered noble, as despicable, cunning, vindictive individuals.

2. Yojimbo (Akira Kurosawa, Japan, 1961)

Sanjuro is a wandering samurai whose roaming eventually leads him to a secluded village, where the inhabitants live under the terror of two rival gangs, one headed by Seibei and one by Ushitora, who are locked in a perpetual struggle for domination.

Sanjuro decides to play one gang against each other in order to eliminate both of them. However, his plan is jeopardized by the appearance of the brother of Ushitora, named Unosuke, who owns a revolver.

Akira Kurosawa directed this film in an effort to depict the violence and corruption that dominated Japan during the 1860s. With his satirical style, he sheds light on a slice of Japanese history, combining all the elements of a Western: gangs, gamblers, deserted streets, terrified inhabitants, taverns, corrupted men of power, even guns.

Toshiro Mifune as Sanjuro and Tatsuya Nakadai as Unosuke are magnificent in their respective roles.

1. Woman in the Dunes (Hiroshi Teshigahara, 1964)

One of the most renowned Japanese films in the West, “Woman in the Dunes” won the Jury Special Prize in Cannes and received Oscar nominations for Best Foreign Language Film and Best Director.

Junpei Nikki is a teacher and an amateur entomologist. During one of his excursions in a sandy area of Japan, where he has arrived to collect insects, he misses the last bus. Having no other choice, he agrees to spend the night in a nearby village. The inhabitants make him ascend a ladder in a sand pit, where he is to share the house of a widow.

However, the next day, he discovers in terror that the villagers have retracted the ladder, and are determined to leave him in the pit forever, in order to have children with the woman and to help her shovel sand. If that was not enough, he realizes that if they ever stop shoveling sand, they will drown in it.

Hiroshi Teshigahara directs an allegorical film, a parable, about society and politics. In that fashion, the villagers represent the authorities, and the two protagonists represent the working class. According to Teshigahara, the inhumane authorities do not hesitate to enslave the working class with false pretences in order to achieve their goals.

Hiroshi Segawa’s black-and-white cinematography is astonishing, and the two protagonists, Eiji Okada and Kyoko Ishida, are magnificent in their parts.

Author Bio: Panos Kotzathanasis is a film critic who focuses on the cinema of East Asia. He enjoys films from all genres, although he is a big fan of exploitation. You can follow him on Facebook or Twitter.