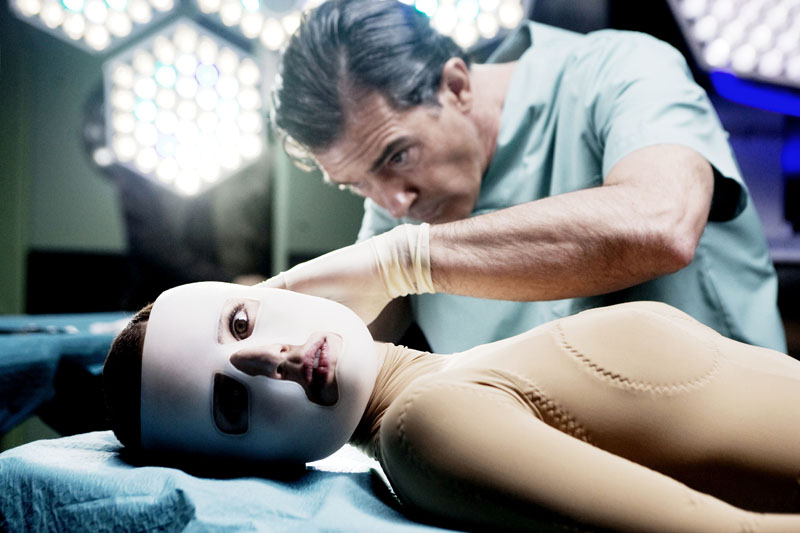

7. The Skin I Live In (2011)

Pedro Almodóvar’s Spanish psychological thriller based on Thierry Jonquet’s novel “Mygale” follows Robert Ledgard (Antonio Banderas), a plastic surgeon working on “GAL”, a resistant artificial skin which is unaffected by insect bites or burns.

At a medical symposium, he privately confides to a colleague that he has not only been testing mice, but has also been conducting illegal transgenic experiments on humans, after which, he is prohibited from further research.

Despite being forbidden, Ledgard continues his work with his loyal servant, Marilla (Marisa Paredes) and his experimental subject, Vera (Elena Anaya). Vera is held captive in a locked room which contains a television, hand-knit dolls, yoga equipment, security cameras, and a wall plastered in her handwriting.

Many of Almodóvar’s trademarks like obsession, confusion, sexual identity, gender ambiguity, secrets, betrayal and death, combined with his ventures into new genres like science fiction and horror lead to a refined melodramatic classic with a vengeful core. Inspired by Georges Franju’s “Eyes Without a Face” and Fritz Lang’s thrillers, the heart-throbbing pace of the screenplay and the earnest exposition stories of the characters lead to the puzzle of the film slowly being solved.

With each line of dialogue spoken and every character’s movements; the audience works out, piece by piece, everything that happened before, everything that is happening now, and everything that motivates the characters to do what they do.

Typical of Almodóvar, the film’s design, costumes and colour are beautiful and uniquely stylistic thanks to his frequent collaborators – production designer Antxon Gómez and cinematographer José Luis Alcaine, together with Alberto Iglesias’ suspenseful music creates an intense, clinically chill feeling that is unusual for Almodóvar, but nonetheless fitting.

It premiered at the 64th Cannes Film Festival, and won Best Film Not in the English Language at the 65th BAFTA Awards. It was also nominated for the Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film and 16 Goya Awards.

6. Night and Fog (1955)

Alain Resnais’ French documentary short acts as a lasting reminder of what human beings are capable of doing to one another. The first film to truly address the Holocaust, it was only made ten years after the liberation of Nazi concentration camps.

Resnais collaborated with scriptwriter Jean Cayrol, a survivor of the Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp in order to truthfully document the Nazi’s atrocities and inhumanity. The thirty-two minute film attracted a lot of controversy and faced difficulties with French censors, especially when trying to enter Cannes.

Narrated by Michel Bouquet, the documentary attempts to describe the rise of Nazi ideology and its quick escalation from thought to action to sadism that included torture, scientific and medical “experiments”, executions, and prostitution.

The diffusion of responsibility, blame and denial are at the film’s core as Resnais and Cayrel question who was responsible for these atrocious horrors. They show how many people involved in the death camps didn’t know how to deal with their own guilt and complicity or didn’t want to.

Juxtaposed black-and-white archival footage of concentration camps and their victims in pastoral colour footage of the buildings and locations ten years later, Resnais used stock footage from France, Belgium, and Poland, but conspicuously not from Germany, and chillingly alternates between past and present.

The film documents skeletal nude corpses being hung, it shows how the Nazi ‘s utilised the victims’ remains as much as possible, it bears witness to the gas chambers and crematoriums, and even includes footage of the dead being bulldozed into mass graves.

5. Das Experiment (2001)

Oliver Hirschbiegel’s German thriller film based on Mario Giordano’s novel “Black Box” and Philip Zimbardo’s 1971 Stanford prison experiment follows Tarek Fahd, a taxi driver who finds a newspaper advertisement calling for participants for an experiment with a compensatory pay of 4000 German marks.

Tarek becomes interested not only for the cash payment, but also sees the experiment as a potential story since he used to be a journalist. He pitches the idea to his ex-boss, who reluctantly agrees and provides Tarek with a pair of glasses with a built-in mini-camera.

The social experiment is led by Professor Klaus Thon and his assistant, Dr. Jutta Grimm. Attempting to see how provided ‘roles’ change people’s behaviours and mentalities, they stimulate a prison situation in which they split their 20 volunteers into two groups; guards and prisoners.

In the experiment, the prisoners lose their civil rights and have to obey arbitrary rules like only wearing nightshirts, only referring to one another by their provided prisoner number (Tarek is prisoner number 77) and they must obey the guards’ orders.

The guards are given nightsticks, but are told not to use violence. Within a couple of days, the situation escalates as psychological changes develop as the guards become excessively aware of their power and manipulate the prisoners’ fear of humiliation.

Heavily inspired by the famous Stanford Prison Experiment of 1971, the film was remade in America in 2010 by Paul Scheuring and stars Adrien Brody and Forest Whitaker. Both of these films utilise some aspects of the real experiment and dramatise others, such as Tara being a journalist with videotaping glasses.

Probably the film which has remained the most true to the original social experiment is the recent 2015 American thriller, self – entitled, “The Stanford Prison Experiment” starring Billy Crudup, Ezra Miller, and Michael Angarano.

4. Eyes Without A Face (1960)

Georges Franju’s French horror adaptation of Jean Redon’s novel follows Dr. Génessier (Pierre Brasseur) who does everything he can to attempt to fix his daughter’s, Christiane’s, (Edith Scob) face, after it is horrifically disfigured in an automobile accident that he caused.

He experiments on his pet dogs to work on possible treatments while his daughter’s face remains hidden by an expressionless, stiff, white mask that covers everything but her eyes and resembles her face before the accident.

Dr. Génessier’s loyal assistant, Louise (Alida Valli), grooms young women with similar facial structures to Christiane into following her to Dr. Génessier’s house (and attached clinic). The two kidnap and chloroform the women and perform heterograft surgeries on them to try and restore Christiane’s face. However, following several unsuccessful attempts, Christiane becomes even more depressed as her life outside fades away.

Franju’s quietly absurd horror is poetically brutal refuses to cut away from the graphic images as he brings life to the stock characters of a mad scientist, his assistant, and his monster in a strangely sensitive and incredibly cerebral way.

The only foray into horror genre by the cofounder of the Paris Cinematique, the film has influenced several directors and films, including Spanish director Jesús Franco “The Awful Dr. Orloff” (1962) , the Italian film “Atom Age Vampire” (1961), the British film “Corruption”, (1968), John Woo’s action film “Face/Off” (1997), Pedro Almodóvar’s “The Skin I Live In” (2011), as well as influencing John Carpenter’s expressionless mask for the Michael Myers character in the slasher film series Halloween.

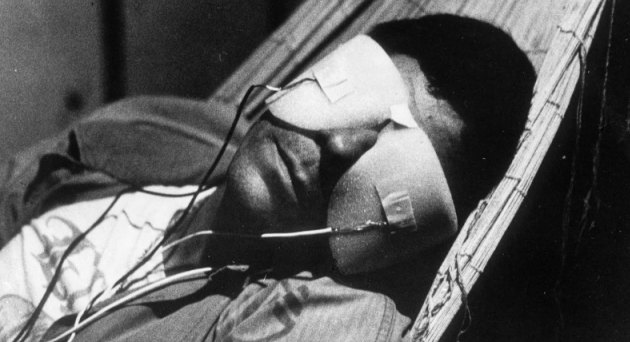

3. La Jetée (1961)

Chris Marker’s French science fiction short film is narrated by an unnamed man (Davos Hanich), who is a prisoner in the aftermath of World War III in a post-apocalyptic Paris.

Scientists are researching time travel in order to reconstruct their society and experiment on the protagonist, whose psychological link to the past is a vague pre-war memory of a beautiful woman (Hélène Chatelain) on the observation platform at an airport, shortly before some chaos arises and a stranger is mysteriously shot.

The experimenters utilise him and send him on multiple trips to the past and attempt to send him to the far future so as to find powerful technology which might help them in their present.

Constructed almost entirely from still photos and diffusing transitions, the twenty-eight minute black-and-white featurette relies on sound design, visually economic photographs, and emotional narration.. It won the Prix Jean Vigo for short film and went on to inspire Terry Gilliam’s 1995 science fiction cult classic “12 Monkeys”.

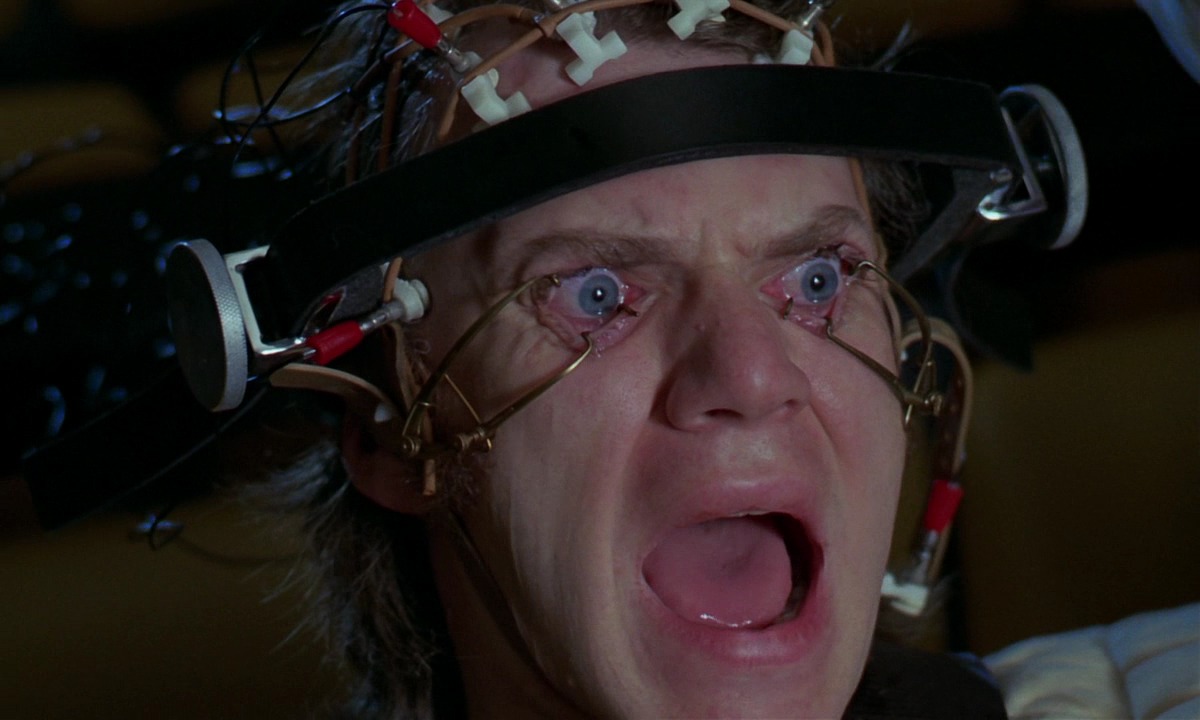

2. A Clockwork Orange (1971)

Stanley Kubrick’s most controversial film based on the dystopian 1962 novel by Anthony Burgess’s , was withdrawn from the United Kingdom by Kubrick himself for nearly thirty years due to its heavily criticised response.

The social sci-fi fable follows delinquent Alex De Large (Malcolm McDowell), a charismatic intelligent youth who gets a kick out of pornography, breaking the fourth wall, Beethoven and going on vivid, random rampages of “ultraviolence” with his bowler hatted, Doc Martin wearing, white overall-clad gang of “Droogs” (buddies).

Their vicious conquests include crippling strangers, raping defenceless women while singing renditions of “Singin’ In The Rain”, breaking into homes, getting intoxicated on drug-ladened “milk-plus”, and just beating up anyone who happens to pass by.

Eventually, Alex gets caught for one of his crimes and goes to prison. However, two years into the sentence, he gets the opportunity to become a test subject for the Minister of the Interior’s new Ludovico technique, an experimental aversion therapy for rehabilitating criminals within two weeks and then released.

Similar to behaviour modification techniques like Watson’s Classical Conditioning or Skinner’s Operant Conditioning, Alex is strapped to a chair, has his eyes clamped open, injected with drugs, and forced to watch nauseating films of sex and violence coincidentally set to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, his favourite one.

The conditioning treatment is successful and leaves Alex unable to engage in any sexual thoughts or violent actions, even in cases of self-defence. The prison chaplain complains Alex has had his free will stolen from him and that he is has not chosen to be good and asserts that goodness can only come from within.

However, the prison governor states that the Ludovico technique will cut down crime and help prevent prison over-crowding. Alex gains his freedom back, but at the cost of becoming dangerously ill every time he tries to act violently, thinks of a woman sexually, or listens to his blessed Beethoven.

Stanley Kubrick described the film as “…A social satire dealing with the question of whether behavioural psychology and psychological conditioning are dangerous new weapons for a totalitarian government to use to impose vast controls on its citizens and turn them into little more than robots.

This bold, thought provoking satire of society’s hypocrisy, corruption and sadism stylistically analyses institutionalised brutality and the fragility of individuality and personal rights in a startlingly funny way.

The extreme wide-angle lenses and blended classical and synthetic soundtrack provide a nightmarish aspect the film that is brilliantly punctuated with rhythmic utilisation of fast and slow motion that effortlessly stylize the violence and sex scenes, due to their off-beat pacing.

The film was nominated for several awards including Academy Awards for Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, best Film Editing and Best Picture, as well as BAFTA nominations acknowledging the art direction, cinematography, and soundtrack. McDowell was also nominated for a Golden Globe for his chilling portrayal as Alex.

1. Frankenstein (1931)

James Whale’s Pre-Code horror classic based on the play by Peggy Webling, which in turn is based on Mary Shelley’s novel of the same name), follows Dr. Henry Frankenstein (Colin Clive), a young, overachieving scientist, who, together with his hunchbacked assistant Fritz (Dwight Frye), steals human body parts and pieces them together to form a new body for piece together a human body that they can experiment on.

Frankenstein longs to create life, not only for the benefit of science, but to know what it feels like to be God. He finally succeeds with a crash of thunder, sparking electrical machines and chilling lightning as his built-together body finally comes alive (Boris Karloff). However, Fritz mistakenly gave the body a criminal, murderous mind and hysteria results.

Considered to be a cornerstone of the genre, the film’s iconic look is still being replicated today. Universal’s make-up genius, Jack Pierce, devised the monster’s unique appearance, with his electrified flattop hairstyle, neck bolts, heavy eyelids, elongated scarred hands and shoulder-padded, shabby suit that seemed to predict 80s fashion, managed to make him appear scary, but also translated the monster’s naivety and innocence.

The monster ironically evokes sympathy due to the horror mainly coming from people’s fierce hysteria and fast-paced judgement.

Karloff’ starred in the next two sequels, “Bride Of Frankenstein” (1935) and “Son of Frankenstein: (1939). Frankenstein’s story also continues in, “The Ghost of Frankenstein” (1942), “Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man” (1943), “House of Frankenstein” (1945), and many more, including Mel Brooks’ “Young Frankenstein” (1974) . Kenneth Branagh also remade this film in 1994 with Robert De Niro starring as the monster.

Author Bio: Susannah Farrugia is an undergraduate Psychology student at the University Of Malta. Her life is measured in films and television shows. She enjoys drawing scenes and designing posters based on the films she has seen.