14. The Evolution of the Hula Hoop (The Hudsucker Proxy)

This underseen homage to screwball comedies features a montage of brilliant comedic skill and visual storytelling. Rather than stick to simple dialogue-driven exposition, the Coens employ some wonderfully inventive images to convey the rise of the hula hoop.

The invention has been conceived by the lovable and idiotic president of Hudsucker Industries (Tim Robbins in maybe his most likable roll ever), only appointed to the position by company board in an effort to drive down the stock price so they can buy it cheaply.

For a whole it seems that their plan has worked, as the hoop fails to sell and retailers drop the price continually. But through an inexplicably ridiculous series of events the prices begin to skyrocket and the hula hoop is a massive success.

How easy would it have been to convey that in just a few spoken sentences? But Joel and Ethan went out of their way to create a unique and unpredictable presentation. We as the viewer know what is coming. So instead of using a simple or conventional method, the Coens turn it into a wonderful sequence of silent comedy, turning every shot into a visual gag that can advance the story, subtle tones, motifs and style of the movie.

13. Visser’s Death (Blood Simple)

In a movie filled with themes of fate, conscience and circumstance, is there a better way to culminate such a rollercoaster ride than an accidental shooting, executed for reasons neither character really understands? This showdown is the result of countless misunderstandings, too many poor decisions and numerous inaccurate assumptions.

The Coens expertly use the contrast of dark and light to drum up the tension as well as the whole use of lighting in general. Consider the brief moment in which Visser’s shadow flickers across the door, or the narrow beam of light left by the shot that kills him as excellent methods to emphasize each character’s split second decision and ultimate result.

This climax could easily have been farcical and comedic if the Coens wanted it to be, but instead the only humour to be found is through the tragic irony of the situation. The brutality and terrifying nature of the scene make the it utterly haunting and endlessly memorable.

12. Look in Your Heart (Miller’s Crossing)

When the Coens make a movie in the gangster genre, they don’t set out just to tell a simplistic crime story. They want to examine the process, explore every detail and analyse ever fissure of the gangster environment. Part of this detail is to demonstrate how human emotions play into this world of mobsters and murder and how they navigate this violent world.

That is what makes Miller’s Crossing so compelling and engaging, it’s also exemplified as the driving force of this scene, in which Gabriel Byrne‘s Tom is forced to take John Turturro‘s Bernie out into the woods and execute him.

The sequence is unnerving and unsettling, as Bernie screams and begs for his life in a tone that is almost beyond desperation, refusing to go down in a quiet and noble fashion while Tom just stares blankly at him, an unreadable expression on his face.

The fact that one can’t read Tom’s expression makes it all the more captivating as the scene is played out for extreme levels of tension. It ultimately injects a sense of unpredictability as by this point in the movie we already know that these characters are acting from their emotions and their next actions are far more difficult to predict. The sombre tone of the scene, as well as the haunting score and quiet visual poetry seek to emphasize these elements and make it an astonishing piece of filmmaking.

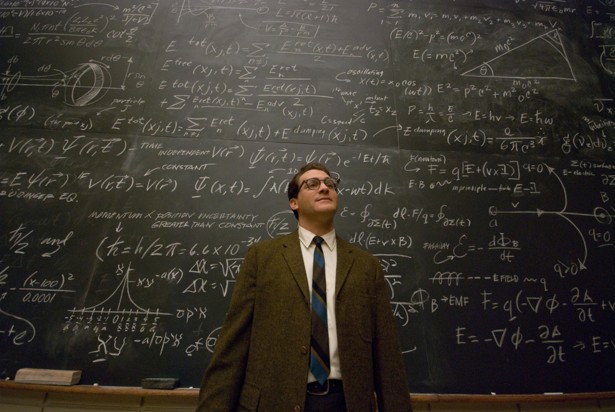

11. The Uncertainty Principle (A Serious Man)

A Serious Man is a film about a man searching for answers, and when the right answer is staring him right in his face, he isn’t aware of it. But of course the sad truth is that he simply cannot accept that as an answer. Larry Gopnik lives in a world that seems determined to deprive him of everything he wants in life, to spoil every chance, opportunity and virtue he thought he possessed.

It draws from the core rule of comedy, that all humour is based on pain. In the case of A Serious Man Gopnik’s pain is drawn not from his downward spiral, but by the uncertainty of it all. Religion offers no easy answers, his prayers go unanswered so either there is no higher entity or if god does exist he clearly doesn’t care about him.

This amazing dream sequence acts as a summary of the conundrum the film presents. Larry Gopnik is at first involved in the teaching of the uncertainty principle and then in a debate about advanced physics, the nature of mathematics, the philosophies of logic, probability, and even spiritualism, turning the film into a marvellous physical comedy.

All the while Gopnik is dwarfed by the mighty equation that explains everything, in his own words “it proves that we can’t ever really know what’s going on”.

10. Hiding in the Wardrobe (Burn After Reading)

This is an exquisite scene in every sense of the word, from the suspenseful build up, the work of the actors involved, the tone and eventual payoff all work perfectly. With fitness trainer Chad Feldheimer (Brad Pitt) finding himself way over his head and hiding in the wardrobe of U.S Marshal Harry Pfarrer (George Clooney) the events that unfold are tense, thrilling and ultimately hilarious.

Pitt’s dumb expressions upon realising exactly how much danger he is in are priceless, as we see the unfolding scenario purely from his limited viewpoint from within the wardrobe. We trace Clooney’s actions and footsteps, waiting for any chance through which Pitt can escape, but it never comes. It creates such a sense of entrapment and helplessness for the audience that it’s hard not to hold your breath with Chad.

The fact that the finale is so sudden and almost unexpected is only half of what makes it great. The concept of it being so perfectly set up and executed with such conviction and ruthlessness makes it oddly satisfying.

Ultimately the end result would not be hard to predict had we been given a moment to think about it, we know Harry is paranoid and suspicious of organisations sending people after him. When Chad suddenly catches a glimpse of a holster without a gun in the wardrobe, it gives an indication of what is about the happen and just a few seconds later it does.

9. A Man of Constant Sorrow (O Brother, Where Art Thou?)

Even though the song itself is wonderful and beautifully filmed, the setup is just as brilliant to watch and analyse. The gleefully subversive way in which Ulysses Everett McGill (George Clooney) improvises his way through a pitch to appear on the radio in front of its blind manager, making up the group name ‘Soggy Bottom Boys’ and claiming to be “negroes, all except our accomp… uh, company… accumpli… uh, the fella that plays the guitar” only for the station owner to announce that he “doesn’t do negro songs”, only for the group to admit that they are not what they claimed to be “except for the accompaniment”.

But then of course, we move straight into the song itself. The showcase of this cover of Man of Constant Sorrow rocketed the song to be a surprise hit of 2000 The song, with lead vocal by Dan Tyminski, was also included in the film’s highly successful, multiple-platinum-selling soundtrack. This recording won a Grammy for Best Country Collaboration at the 44th Annual Grammy Awards in 2002.

But then by the end of the scene there’s one more little gem of dialogue to be found as McGill confesses to the bind owner that when it comes to agreeing to the terms of their payment of $10 each that two members of their four man group will have to sign with an X as “only four of us can write”.

8. Hotel Shootout (No Country For Old Men)

There are few scenes that stand as a better example of the Joel and Ethan’s directorial genius than the hotel shootout from No Country For Old Men. Having tracked Josh Brolin’s Llewellyn Moss down to a seedy hotel near the American/Mexican border, Javier Bardem’s psychopathic hitman Anton Chigurh makes his move and attempts to obtain the stolen drug money while also trying to kill Moss on the process.

It is a masterfully constructed game of cat and mouse that starts in the claustrophobic confines of the hotel room before spilling out into the open streets. Yet somehow through all of these changing environments the Coens maintain a vivid sense of tautness and rigidity to the firefight.

The whole sequence is only further emphasised by the silent, dark and patient waiting that proceeds it as Moss prepares for his attackers arrival. It only makes the sudden onslaught of noise and movement all the more unsettling.

Another amazing aspect about the scene is how restrained it is. The directing siblings were clearly after a sense of hyper realism and it’s fair to say they achieved just that.

What is even more commendable is that fact that the two duellists, the protagonist and the antagonist, never meet face to face, they never even share the screen together, always occupying different shots and yet their connection is always felt and constantly engaging.