8. A Boy and His Dog (1975)

Set amidst a post-nuclear war wasteland in the year 2024, L.Q. Jones’ amoral tale of survival, this quirky freak out film inaugurated the post-apocalyptic genre with this cruel cinematic smorgasbord. Based off Harlan Ellison’s award-winning novella,

A Boy and His Dog stars a baby-faced Don Johnson as Vic, a shady scavenger who roams the wastes with his telepathic dog, Blood. When the duo stumble upon the suspicious and sexy Quilla June (Susanne Benton), a denizen of an underground society deep below the earth’s surface, Vic follows her down into the surreal depths.

As a doomsday fable of pitch-black proportions, A Boy and His Dog is quite singular, and sinister, and wonderfully hard to shake.

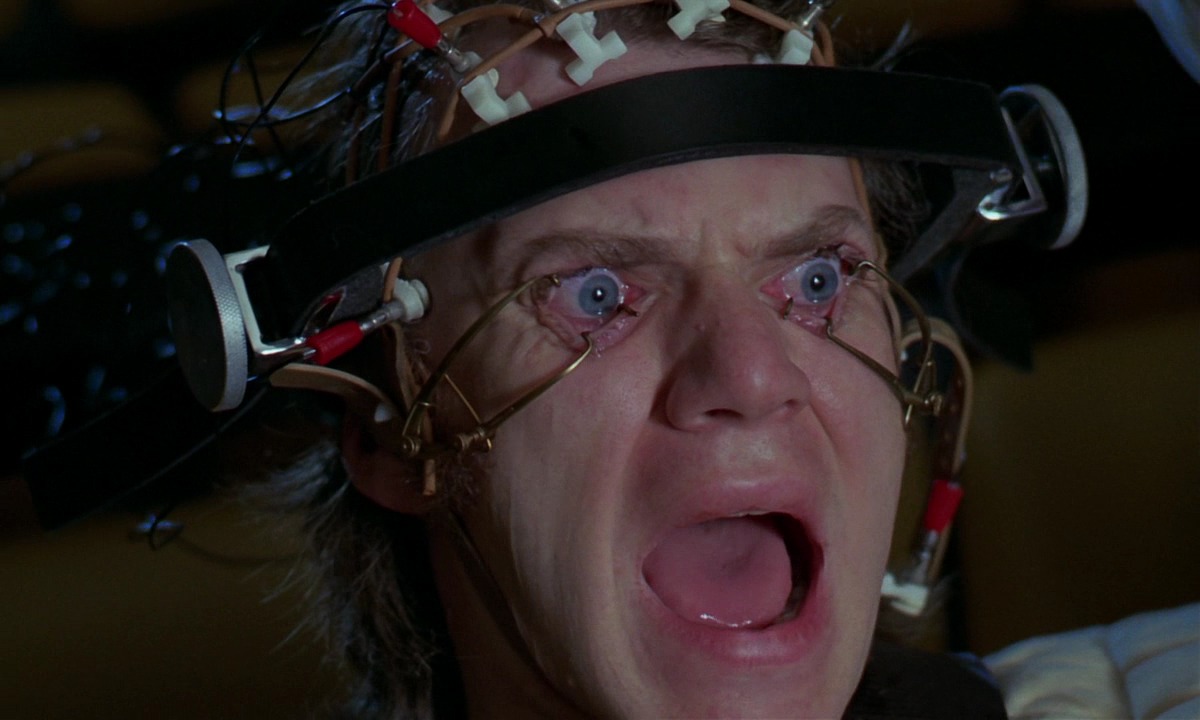

7. A Clockwork Orange (1971)

A dystopian crime saga that brought the term “ultra-violence” to the mass cult, Stanley Kubrick’s controversial A Clockwork Orange makes a meal out of the Anthony Burgess source novel and results in a film you either love or hate but will certainly never forget.

In a crime-addled futuristic England a young thug named Alex (Malcolm McDowell) leads a gang of volatile youths, “droogs”, on a crime spree involving theft, rape, and murder, all to the keys of Ludwig van Beethoven.

Once in police custody Alex undergoes the Ludovico technique, a nasty brand of aversion therapy that may or may not cure him and society at large should it all play out accordingly.

While Kubrick’s film showcases the technical skills that made him a legend, and the Moog-saturated score is first-rate, the lengthy scenes of abuse, misogyny, and mayhem may prove too much for sensitive viewers, and certainly portraying a rapist home-invader as sympathetic will not wash well with many.

If these caveats can be set aside A Clockwork Orange is an iconic, thought-provoking, and outrageous spectacular. Chilling, hypnotic, blackly humorous and accusatory, it’s a nightmare worth experiencing and appreciating.

6. Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978)

Philip Kaufman’s 1978 paranoiac sci-fi thriller works on primal fear and excels at making the familiar terrifying. Not the first time Jack Finney’s novel was adapted––Don Siegel did it in 1956, Abel Ferrara in 1993, and most recently Oliver Hirschbiegel in 2007––and the other interpretations offer decent chills, but something about the Kaufman version absolutely mortifies.

Partially due to W. D. Richter’s marvel of a screenplay that ratchets up the tension while providing a multi-protagonist cast of the highest order to realistically cope with a terrifying outer space invasion on a personal level. The brilliant cast, led by Donald Sutherland also includes Brooke Adams, Robert Duvall, Jeff Goldblum, Leonard Nimoy, and Don Siegel.

Not since Vertigo has San Francisco, as lensed by Michael Chapman, looked so haunting, dream-like, and touched with hidden menace. Invasion of the Body Snatchers also boasts one of the most scream-inducing surprise endings ever to keep you up at night. A hybrid of horror and SF, it’s an unforgettable classic.

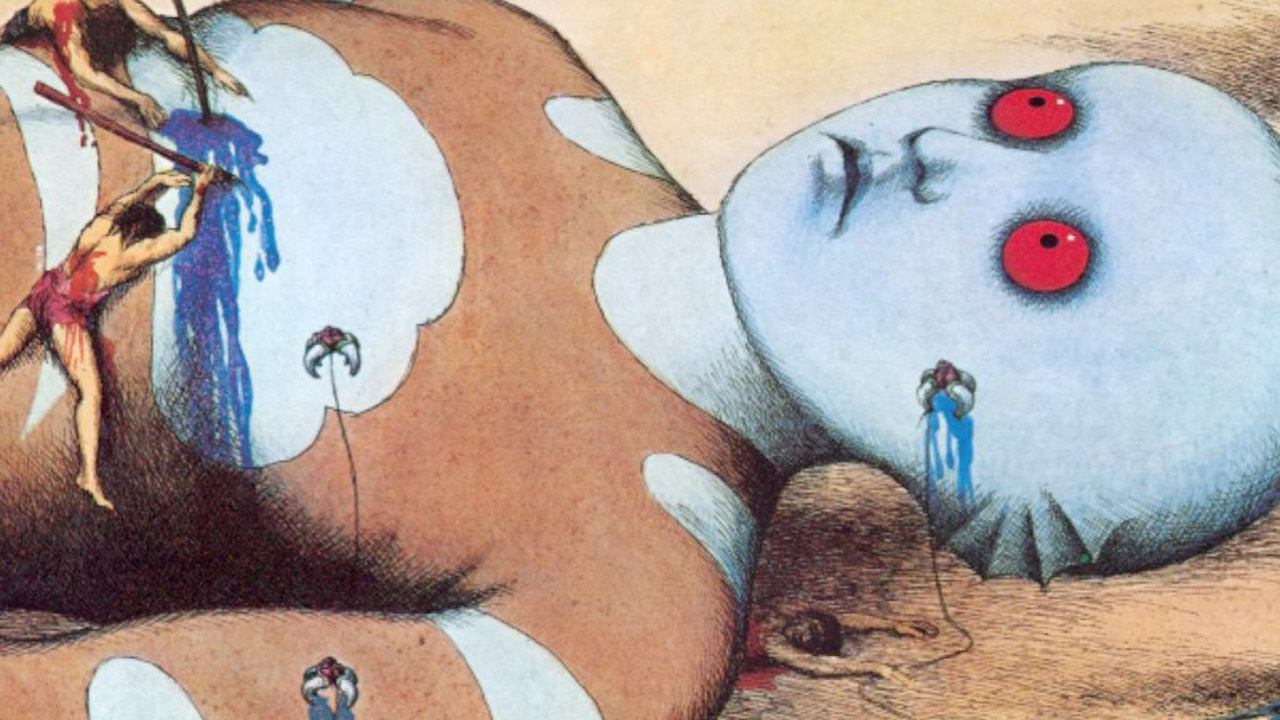

5. Fantastic Planet (1973)

Overrunning with warm pastel colors and delicate, sharply detailed drawings, René Laloux’s underground animated French classic Fantastic Planet is an influential mindfuck, make no mistake. Adapted from Stefan Wul’s pulpy 1957 French sci-fi novel “Oms en série”, Fantastic Planet is an allegorical odyssey, one that embraces psychedelic visuals, originally inspired by Russia’s invading of Czechoslovakia.

Set on the planet Ygam exists a race of blue-skinned giants, Traags, who keep a human like race, Oms, as pets. Alternately surreal, deeply eerie, high-flown, and frightening, Fantastic Planet is a nagging, nostalgic, and often disconcerting epic of animation that is as original as it is, in it’s own way, monumental. Deserving of the 1973 Cannes Grand Prix Prize, midnight movies are seldom this observant, imaginative, and yes, mind-blowing. Not to be missed.

4. Alien (1979)

In Ridley Scott’s shocking sophomore film (he’d made The Duellist in ‘77) the titular alien is a biomechanical organism that’s pleased as punch to reproduce itself aboard a claustrophobic spaceship, the Nostromo. The perfect distillation between sci-fi and horror, Alien rightly presents itself as the ultimate “don’t look behind you” fright flick, with the perfect memorable tagline: “In space no one can hear you scream”.

So much of Aliens is now regarded as classic, from the iconic turn of its fearsome female protagonist Warrant Officer Ripley––a stunning and iconic Sigourney Weaver––to H.R. Giger’s phallus-resembling acid-blooded monster, not to mention Ron Cobb’s and Chris Foss’ stunning art design and Dan O’Bannon’s hit-all-the-right-marks screenplay, Alien is a nasty, teeth-gnashing tour de force. Bonus marks for the chest-popping first appearance of the eponymous outsider, certainly one of film history’s greatest ever entrances.

3. Solaris (1972)

Without the benefit of a hefty and helpful budget and produced during Soviet pogroms against free expression, Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris remains a landmark film that ruminates on loss, longing, memory and what it means to be alive.

Adapted from the great novel by sci-fi legend Stanislaw Lem, Solaris concerns itself not with space opera, explosions, and special effects but with philosophical speculation and poetic perceptions, and the results are equal parts idiosyncratic, disturbing, and deeply strange, and never less than completely compelling.

Psychologist Kris Kelvin (Donatas Banionis) agrees to examine the crew of a space station orbiting the eponymous planet Solaris, a mysterious orb that seems to have its own pull on the psyches of those in her midst. As Kris, who at one point suggest that “whenever we show pity, we empty our souls,” realizes that Solaris can recreate the memories of visitors, including that of his long-departed wife Hari (Natalya Bondarchuk), Tarkovsky strikingly toys with color symbolism and almost gauche religious imagery.

A heady mixture of arthouse, mental anguish, spiritual landscapes, and overwhelming melancholy, Solaris is a deeply felt narrative, one that unhurriedly unfolds on the grandest of scales, it’s also one of the most absorbing instances of speculative cinema ever wed to celluloid. A masterpiece by any measure.

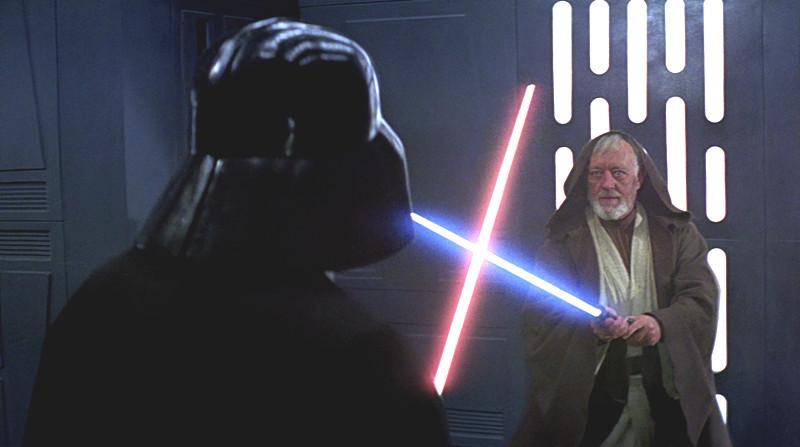

2. Star Wars (1977)

Not putting George Lucas’ stellar space opera in the top spot is sure to upset the diehards, and there’s no denying the scope, the vision, the craft, and the nostalgia behind Star Wars, one of the most identifiable and enjoyable franchises in film history. It’s tops in most people’s books for good reason and from the opening orchestral salvo from John Williams to that all too familiar opening title scroll, everything about Lucas’ pet project screams pièce de résistance.

Geniously reworking Akira Kurosawa’s Hidden Fortress (1959) and using a Joseph Campbell derived blueprint of the heroic journey, Star Wars would go on to become not just a pop culture touchstone, an endless sci-fi franchise, but also a surprisingly complex mythic adventure earmarked as perhaps the most influential and recognizable movies of the decade.

“May the Force be with you,” became a familiar mantra and its then unknown leads––Carrie Fisher, Harrison Ford, and Mark Hamill––would each become household names.

Star Wars’ rescue-a-princess-and-save-the-galaxy premise was a simple one, but hung on panoramic vistas of impossibly far away planets, hinging on sophisticated and enthralling makeup effects and set designs, this was world-building and imagineering at a whole new level.

The blockbuster model was redesigned, the fireworks on a scale so grand it would alter the face of populist cinema forevermore. Pop storytelling and awe hit a new high water mark with this, the greatest of all space operas, and a movie that must be experienced to really be properly appreciated.

1. Stalker (1979)

Perhaps deceptively derived from Arkady and Boris Strugatsky’s great 1972 sci-fi novel of big ideas, “Roadside Picnic”, Stalker is an intuitive and uncanny masterpiece from Andrei Tarkovsky.

Teeming with dense visual detail, Stalker unfolds some time after aliens have visited and left the Earth, as the novel details: “…leaving behind a number of artefacts of their incomprehensibly advanced technology. The places where such artefacts were left behind are areas of great danger, known as ‘Zones.’’

The film follows three men––the Writer (Anatoliy Solonitsyn), the Scientist (Nikolai Grinko), and the Stalker (Alexander Kaidanosky)––as they journey through the Zones. It’s understood that somewhere within the Zones exists the Room, where wishes are granted, and where each man, dissidents, have a calling to enter. Is it self-discovery that awaits them in this offbeat and bizarro reworking of the Wizard of Oz via a Kafkaesque winnow?

“As always, Tarkovsky conjures images like you’ve never seen before,” raved Time Out’s Derek Adams, “and as a journey to the heart of darkness, it’s a good deal more persuasive than Coppola’s.”

There’s no denying Stalker’s complex and tilted narrative, and its deeply penetrating philosophical musings do, to a large extent, distance it from populist SF like Star Wars, but for the courageous cinéaste Tarkovsky presents deep, detailed, and far-reaching rewards. As allegory, fantasy, and treatise on art, science, and faith, nothing comes close to the daring ideas and insights Stalker limns. If Stalker isn’t thought of as a masterpiece then the word holds no meaning. Essential cinema.

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.