The spirit of the road has always been deeply embedded within American culture, dating all the way back to the founding fathers and their westward expansion.

In the movies, the provenance of the road movie can be seen in the silent films of the migrating travellers and cowboy pioneers of the 1920’s. By the onset of the 1930’s the movies increasingly took to the modern road, initially in screwball comedy vehicles such as It Happened One Night and Sullivan’s Travels, before a multiplicity of films took the noir template away from the backstreet drinking dens and onto the road in crime thrillers such as Detour, The Devils Thumbs a Ride and Gun Crazy.

This was followed by a lean period for the road movie, but the 1957 release of Jack Kerouac’s book On the Road would result in the road being seen in a new light, the road was not only a means to end for traversing between set locations but also a site for the celebration and freedom of transience over any need for a destination or stability.

This would be taken to heart by the burgeoning New Hollywood cinema movement of the late 1960’s. By the close of the decade, with the Hays Code torn up and the Hollywood old guard no longer bringing in the box office receipts, a new generation were allowed a brief grip on the reigns. This resulted in two benchmark pictures for the road movie. 1967’s Bonnie and Clyde, bringing the violent road noir world bloodily screaming into the 60’s and 1969’s Easy Rider which took the spirit of Kerouac and applied a countercultural lick of paint. Both pictures were huge.

This breakthrough for the road movie as the new hip setting for social and cultural discourse led to a watershed of films during the first few years of the 70’s in which wanderlust became a byword for hipness and existentialism. This willing displacement, which was the source of adventure and discovery for Kerouac’s beat generation 20 years earlier, was now a way of spitting venom upon the bourgeois of middle America, upon the American Dream handed down to a generation fighting against the conformism of their parents. This was a generation with a one-way ticket to I don’t care where.

These factors saw the 1970’s develop into the most bounteous decade for the road movie. Technologically there had been the relatively recent formal development of putting people in actual cars on real roads, meaning the end for verisimilitude ruining back projection, and with the film Bullitt, the development of the camera car which allowed for an exciting sense of danger and velocity to be added to car chases.

These films of the 1970’s also showed us images of a nation hanging on to the last vestiges of pre-homogenisation, before chain restaurants, strip malls and business park culture strangled the character from the landscape.

The following list is not an exhaustive list of the greatest films of the decade (though many of them are), but rather a list which reflects the development of the genre over the decade, reflecting the social mores and fashions of a decade in constant flux. From counterculture rebellion to car chase spectacle. This was the 1970’s on the road.

1. Five Easy Pieces – Bob Rafelson – 1970

Raybert Productions, having tapped into the zeitgeist with unprecedented success with Easy Rider; quickly followed up with Five Easy Pieces.

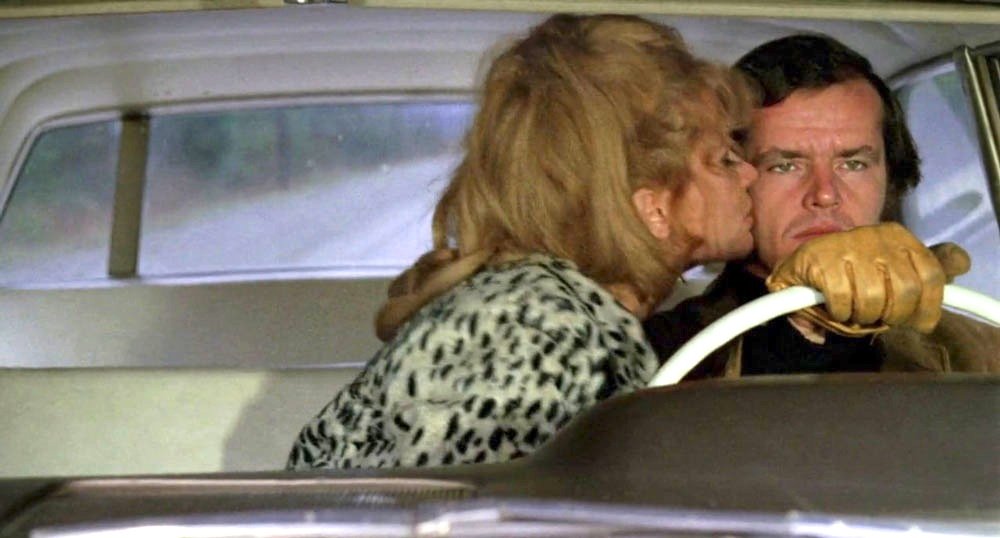

Jack Nicholson, in the wake of his Oscar nominated supporting turn in the biker flick, was now promoted to proper leading man status for the first time after spending 10 years as an AIP also-ran. The opportunity is not wasted; his Bobby Dupea embodies many of the facets of Nicholson’s future work – a conflicted angry man, but with a louche charm which keeps you on his side.

Dupea is a member of a wealthy Washington State family and former piano playing prodigy. But rather than embracing a role as the family scion, he rejects his background choosing to work in the oilfields of Southern California. He continues to struggle with his sense of identity even in this new role, and upon hearing that his father is seriously ill back home, takes a road trip to face up to his past.

Rafelson’s measured direction captures his malady perfectly, giving the film a steady rhythm and allowing time for the locations to become characters in themselves, from the sweaty arid oilfields to the wind and rain swept discontent of the Washington State island on which the Dupea family reside.

2. Duel – Steven Spielberg – 1971

Unlike many of his New Hollywood contemporaries (Coppola, Lucas, De Palma etc), Steven Spielberg was not a ‘film school brat’ but rather earned his stripes through directing network television episodes of Night Gallery, The Psychiatrist and Columbo. This helped him to learn the art of delivering tightly scripted works with a minimal budget and production schedule. An opportunity arose to direct a taut Richard Matheson script about a murderous truck driver, Spielberg was the perfect man.

The plot can be described within the briefest of synopses. David Mann (Dennis Weaver) is driving across south-eastern California when he suddenly finds himself terrorised by the unseen driver of a large tanker truck. After initially toying with Mann, the trucker’s games become increasingly deadly, forcing Mann into a life or death case of flight or fight.

The barebones approach to the plot is complemented by an equally minimal usage of dialogue, which is trimmed down to exclamations of disbelief from Mann, complemented occasionally by (not completely necessary) inner monologues. The soundtrack is equally minimalist, largely making use of the diegetic, such as the truck’s roaring diesel engine and the asinine radio talk shows that emit from Mann’s car stereo.

Our protagonist Mann is a symbol of the cowed middle class. An everyman salesperson under pressure to meet targets, white collar, conventional tie, driving one of the best selling 4 door family saloons of the period in the form of the staidly designed Plymouth Valiant. Mann is a stuffy uptight heart attack waiting to go off.

The unseen driver of the grime ridden, seemingly unstoppable juggernaut that terrorises him is the twisted descendant of the pioneer spirit, a primal road man who can only be countered by Mann shedding the decorum and trappings of corporate America. But enough of that, this is just brilliant bloody fun.

3. Two Lane Blacktop – Monte Hellman – 1971

Monte Hellman had drawn some critical notes if not anything close to success with a pair of elliptical dreamlike neo-westerns during the mid sixties. In this brief wild period for studio commissioning, Universal gave Hellman $850,000 to direct a road racer script extensively rewritten by cult underground writer Rudy Wurlitzer.

Somehow, despite the origins of the writer and director, a Rolling Stone Magazine preview of the film had visions of “A film about road racers and their women, cross-country adventure, the great god speed”. Those expecting such a picture found the resulting vision to be unpalatable to say the least.

The road racer hot rod of the pic is a ’55 Chevy still in primer grey, just to look at the machine we already get a distinct sense of the lack of exuberance to come. Our main protagonists are ‘The Driver’ and ‘The Mechanic’ (musicians James Taylor and Dennis Wilson) who drift from street race to street race just looking for enough money to keep their engine tuned and full of gas. One day they find ‘The Girl’ (Laurie Bird) is sat in their backseat; they don’t bother to question this turn of events.

The only character showing a little ‘joie de vivre’ is ‘G.T.O.’ (Warren Oates) whose bright yellow Pontiac immediately paints him at odds with the Driver and Mechanic. G.T.O. is all bluster and blowhard, whose front of looking for kicks is a cover for a search for companionship. A pink slip race across the country to Washington DC is proposed and agreed. The screen burns out long before the race concludes.

Two Lane Blacktop has a devoted cult following as the textbook example of ‘nihilistic drift’. With an equally devoted list of people who consider it to be the worst car racing film ever made. Hellman is likely fine with such divisiveness.

4. Vanishing Point – Richard C. Sarafian – 1971

The urtext of the car chase flick – a relentless speed addled requiem for the tattered flag of the counterculture. Kowalski (Barry Newman) takes on a near impossible bet to get from Denver to San Francisco in 15 hours to score free amphetamines. He doesn’t make it.

Our man Kowalski is the great American loner in the tradition of Huck Finn on his raft, of Ahab on his single minded mad pursuit. He is, as the film’s one man Greek chorus DJ Super Soul (Cleavon Little) comments “The last American to whom speed means freedom of the soul”.

If this all sounds a little pretentious and affected for a film about someone driving a car really fast, well yes, why not.

Kowalski represents the perfect fuck you and goodnight from the counterculture. The silent majority won – they killed the kids at Kent State – Nixon will get his second term – embrace the roadblock – embrace annihilation.

5. The Getaway – Sam Peckinpah – 1972

You would be hard pushed on paper to find a more perfect pairing of a literary to celluloid transition than allowing ‘Bloody Sam’ to adapt the work of America’s ‘Dimestore Dostoyevsky’ Jim Thompson.

Thompson was the king of a certain brand of pulp Americana in the 1950s, sat somewhere in the hinterland between the hardboiled world of Hammett/Chandler, the skid row underbelly of Bukowski and the fatalist gothic of Cormac McCarthy. There has never been a film adaptation of his work that truly captures his blackly comic world. But this proved to be the best attempt.

Whilst Steve McQueen and Ali MacGraw as the couple on the lam from a heist are a bit too attractive and clean cut to have emerged from the mind of Thompson, we can trust Peckinpah to throw us headlong into his cruel sadistic universe, where there are no heroes and no one is to be trusted as our protagonists scrape through a world of fleapit motels in featureless towns.

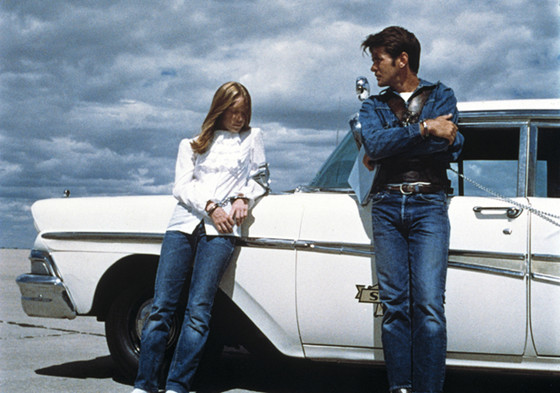

6. Badlands – Terrence Malick – 1973

Terrence Malick has long been revered as the American master of a certain brand of melancholic and beautifully composed ‘visual poems’. He hit the ground running with this, his directorial debut.

The troubled atmosphere of the early 70s had led to myopic nostalgia for the perceived utopia of Eisenhower’s America; Malick pokes this Happy Days Americana right in the eye, with a film loosely recalling the 1958 killing spree of teenagers Charles Starkweather and Carol Ann Fugate.

The Midwestern ‘Big Sky’ locations allow Malick and his cinematographer Tak Fujimoto to embrace an expansive and stunningly beautiful mise-en-scene, laying the groundwork that would lead to what is arguably American cinema’s aesthetic masterwork with his 1978 follow up Days of Heaven.

Malick paints our killer Kit (Martin Sheen) and girlfriend Holly (Sissy Spacek) as products of a burgeoning celebrity obsessed culture. Kit imagines that he’s the star of his own movie, in his mind he’s a James Dean like rebel without a cause, but in reality his individuality is an illusion, he is the banality of evil. Holly is easily impressed by the facade, lost in a world of trashy celebrity magazines, she is our passive narrator. The various killings throughout the film are presented casually and without pathos.

It’s about as cliché as it comes to describe the films of Malick as elegiac, haunting masterpieces. But when the shoe fits…

7. Deadhead Miles – Vernon Zimmerman – 1973

Prior to his directorial debut, Terrance Malick had earned his stripes on script work, including this little seen gem, made in 1971 but left on the shelf until it received a very limited release in 1973 only to then promptly disappear from trace, it’s only availability to this day being through dodgy rips of murky late-night TV showings.

This was surely one of the last road movie studio films to be commissioned on the high of Easy Rider, and probably part of the reason they would soon stop. The counterculture had failed to prove its worth through gate receipts, and films like this, where the narrative never bothers to establish itself, instead favouring a series of loosely strung together vignettes were never likely to set the commercial world alight.

We follow Cooper (Alan Arkin), part of a truck hijacking outfit, who upon acquiring a big yellow Peterbilt, decides to take off on his own series of aimless misadventures. Arkin is one of the more unsung character actors of the period, and his somewhat unhinged post Catch-22 performances could often carry a film on their own, as is the case here with this black comedy for the fried brainpan generation.

8. Electra Glide in Blue – James William Guercio – 1973

Largely overlooked at the time of release, Electra Glide in Blue has built up a steady cult following over the years. Our central protagonist is John Wintergreen (Robert Blake), an Arizona motorcycle traffic cop with aspirations of becoming a detective. Unlike his colleagues whom seem to delight in denigrating hippie scum and such, Wintergreen is the model of moral conviction and decency, making him a subject of ridicule amongst the rest of the force.

Things suddenly begin to look up for Wintergreen when he is given an opportunity to climb the career ladder after correctly indentifying a supposed suicide as a murder. He ends up under the guidance of Senior Detective Harve Poole (Mitchell Ryan), and finds that under the surface this supposed exemplar of straight talkin’ good ole’ boy policing is as corruptible and unstable as the colleagues he’d left behind. Now a disillusioned Candide like figure, Wintergreen returns to his old beat and one last fateful traffic stop.

The film was accused of fascistic and authoritarian sympathies at the time of release, which are unwarranted. The film is another trenchant example of the anxieties of a nation in microcosm. The Electra Glide of the title is a particularly garish Harley Davidson coveted by Wintergreen’s best friend; he eventually acquires the machine through stealing drug money from the murder scene. The bike therefore becomes symbolic of a corruption of the nation’s soul. Where the ‘American Dream’ has been bastardised to signify material wealth and status symbols at any cost.

9. The Last Detail – Hal Ashby – 1973

The Last Detail could never fail, with Hal Ashby on directing duty, Robert Towne providing the script and Jack Nicholson as the main star, the film captures three geniuses at the height of their respective powers.

The plot sees two Navy lifers “Badass” Buddusky (Nicholson) and “Mule” Mulhall (Otis Young) assigned to escort Larry Meadows (an early role for Randy Quaid) to naval prison after the young sailor was hit with a ridiculous eight year sentence for stealing $40 from a collection box (a collection box which unfortunately happened to be for the favourite charity of the Commanding Officer’s wife).

It quickly becomes apparent that Meadows is distinctly lacking in life experience, thus Badass and Mule feel it is their imperative to give Meadows a wild last week of freedom as they travel down a wintery eastern seaboard towards Meadows’ fate.

Nicholson again is perfect, long before his angry riotous turns became mired in self-parody, “Badass” Buddusky is eating himself up inside, trapped in a sense of duality, railing against authority whilst acting on their behalf in a cruel authoritarian miscarriage of justice.

10. Paper Moon – Peter Bogdanovich – 1973

Peter Bogdanovich hit the ground running in the New Hollywood, with several of his early pictures being worthy of any rundown of the period’s great films. One of the most heavily indebted of the New Hollywood generation to his classic Hollywood precursors – whilst his contemporaries were taking notes down the art house revue looking to Godard, Fellini, Truffaut, Bergman et al – Bogdanovich was instead worshiping at the altar of Ford, Welles and Hawks.

His debut Targets was essentially a challenge set down by Roger Corman to build a movie around some stock Boris Karloff footage, with the resulting film somehow being a document of contemporary anomie and paranoia. His second feature is a New Hollywood masterpiece – The Last Picture Show is like the great American novel on celluloid, a melancholy lament for the passing of an era. What’s Up Doc tried to bring new life to the screwball comedy and had its fans.

This, his fourth feature, returns to the black and white cinematography that served him so well on The Last Picture Show, delving even further than that film into the past with its depression era road adventure. Ryan O’Neal and his real life daughter Tatum play a couple of hucksters trying to make a quick buck in the depression, a light hearted flipside to that landmark of depression era road movies The Grapes of Wrath.

Alas this proved to be the last of his film’s to be worth going out of your way for, his preoccupation with a lost Hollywood era resulting in diminishing returns.