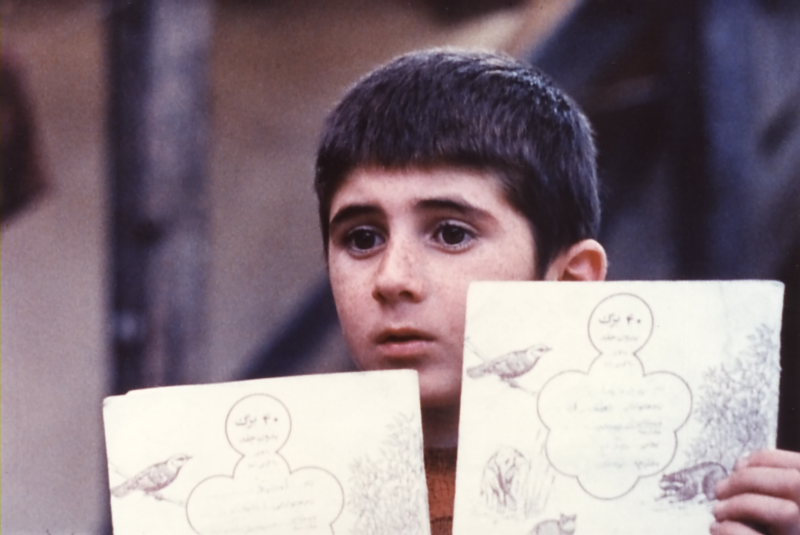

10. Where Is The Friend’s Home? (Abbas Kiarostami, 1987)

The first film of Kiarostami’s “Koker Trilogy” was the one that launched the groundbreaking filmmaker’s – whose later film “Close-Up” would revise the limits of docufiction – international fame to new heights, and for good reason.

The storyline is about a boy’s search for a classmate, in order to give him back a notebook he accidentally took (since that he will need it to write his homework for the next day of school). It may be one of the simplest stories to ever make the big screen, yet it manages to effortlessly offer social commentary.

Life in the village is realistically shown through the naturalistic performances of its inhabitants/actors, while at the same time the film shares a sincere humanistic approach similar to that found in Satyajit Ray’s early films, and achieves that feat inadvertently.

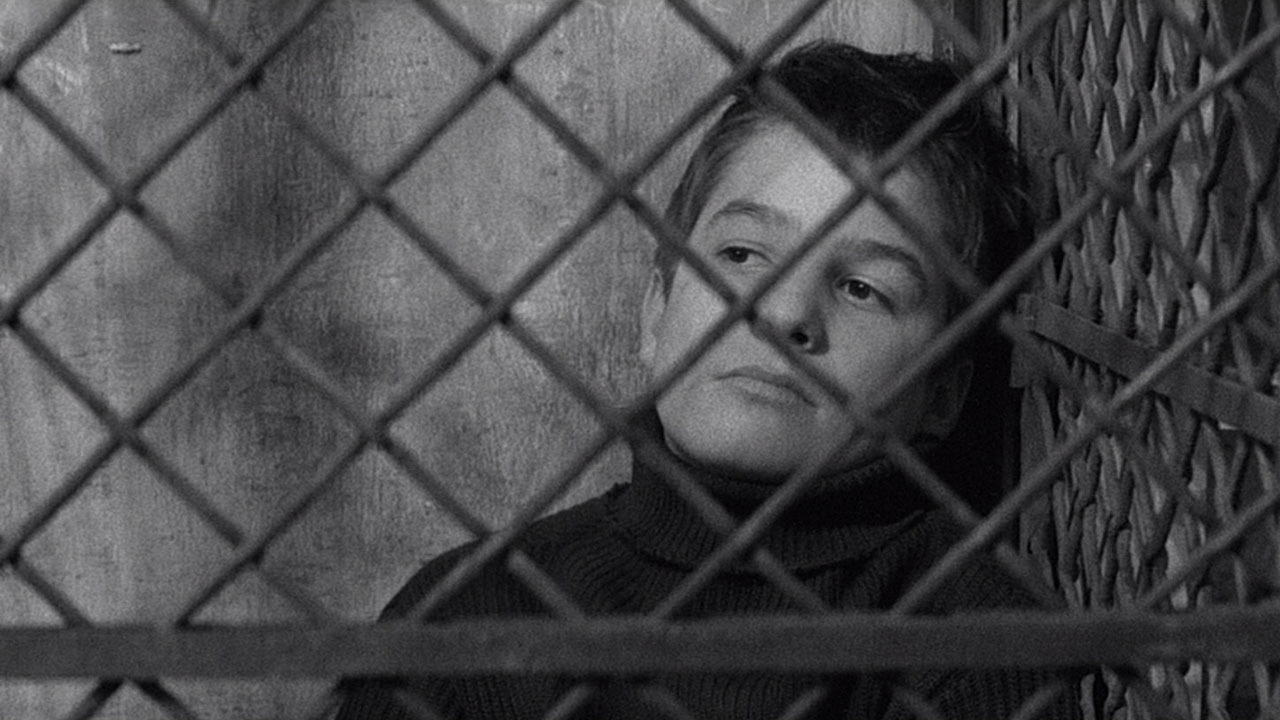

9. The 400 Blows (François Truffaut, 1959)

An undisputable masterpiece of the French New Wave, “Les 400 Coups” derives its name from the phrase “faire les quatre cents coups”, which actually means “to raise hell”. So, the original title was an appropriate one after all…

François Truffaut created his alter ego Antoine Doinel (granting the youngster Jean-Pierre Léaud the role of his lifetime), based on his own life experiences, and used him as a recurring character for four more films. In “The 400 Blows”, the viewers become witnesses of the young boy’s problematic upbringing – as he is constantly forsaken or misunderstood at home and mistreated at school – and his efforts to find self-liberation.

8. The Tree Of Wooden Clogs (Ermanno Olmi, 1978)

“The Tree Of Wooden Clogs” was conceived from stories recited to Olmi by his grandmother, and is widely considered as the director’s most remarkable film to date, since it reveals and celebrates all of his qualities in the best possible way, and in a rather suitable environment.

It is a quiet piece of filmmaking that depicts four peasant families living together in the same farm cluster in Lombardy, all working for the same local landlord. The daily routines and important life events on the farm are enchantingly portrayed in detail by local non-actors, whose real-life backgrounds give a pessimistic but humanist tone to the whole film.

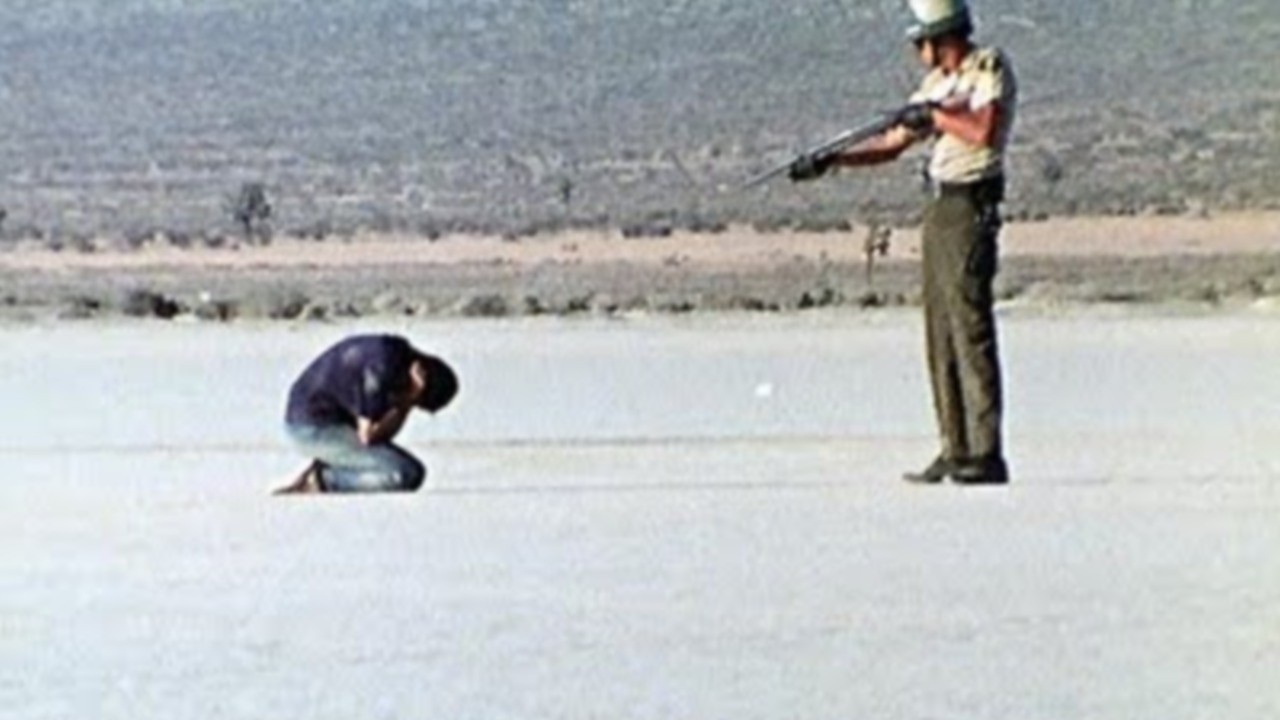

7. Punishment Park (Peter Watkins, 1971)

“Punishment Park” is a stirring 70’s dystopian pseudo-documentary created by arguably the greatest pioneer of docudrama, Peter Watkins.

The year is 1970, and the setting is a dry lake in the Mojave Desert of California. Inside a small tent, arrested members of the anti-war movement and other counterculture groups face emergency trials by kangaroo courts, which consist of mainstream community members and are authorized by the Nixon government. The convicted face the option of doing their time in a federal prison, or spend three days at “punishment park”.

The movie spectators follow a European filming crew’s documentary of those three days, and become observers of a cat-and-mouse game between police officers and convicted protesters. The madly realistic guerilla scenes, and on-camera statements and dialogues (fully improvised by the amateur members of the cast), deliver the proper newsreel feel.

6. The Spirit Of The Beehive (Víctor Erice, 1973)

A period drama with a touch of fantasy, “The Spirit Of The Beehive” is a beautifully shot suspenseful story, which subtly manages to create a detailed psychograph of Spain’s Franco years using plenty of symbolism throughout (since there was no other way to avoid censorship).

The scenario centers on an alienated family living inside a large house in a remote Castilian village. The aging father who cares only about his beehives; the much younger and infatuated – not with her husband – mother; and the two daughters: six-year-old Ana (magnificently portrayed by Ana Torrent), a girl who becomes strangely fond of the monster in the 1931 movie “Frankenstein” after watching the film in a mobile cinema, and the elder sister Isabel, who likes to take advantage of Ana’s credulous nature.

5. The Firemen’s Ball (Miloš Forman, 1967)

The last film Miloš Forman directed before leaving his home country, “The Firemen’s Ball” is a hilarious comedy about the disastrous evening of an annual ball organized by a small town’s fire department, and another fabulous derivative of the Czechoslovak New Wave.

The movie is based on an actual firemen’s ball gone wrong that the director and his fellow writers attended. In order to replicate the feel of their experience, Forman used real firemen and locals for most of the roles, who on their part added a realistic tone to the whole absurdity of the main event of the night.

As a result, the well-meaning characters’ funny and decadent reactions were construed as allegorical parallelisms to the country’s Communist system, and that was the reason behind the film’s permanent ban in Czechoslovakia.

4. La Promesse (Jean-Pierre & Luc Dardenne, 1996)

The first international breakthrough for the Dardenne brothers, “La Promesse” is a devastating social drama that stands as a high point of modern European realistic filmmaking, not only because of the in-depth study of important contemporary themes such as racism and xenophobia in Europe, but also because of the astonishing performances from the cast.

The story focuses on Igor – portrayed by yound amateur Jérémie Renier – a motherless adolescent who, instead of going to school, enjoys a seemingly carefree life, provided that he serves as the right-hand man/conspirator for his father’s crooked working operations; behind the cover of a legitimate construction business, he imports, provides residence, and exploits illegal immigrants. The only professional actor in the cast and Dardennes regular, Olivier Gourmet, portrays his father.

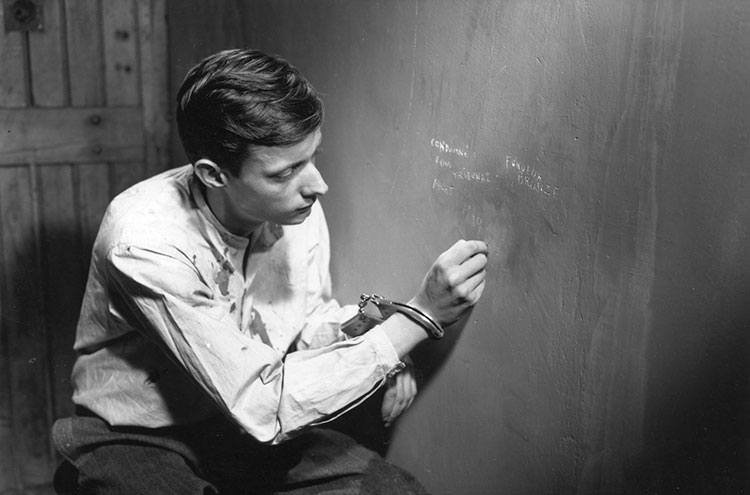

3. A Man Escaped (Robert Bresson, 1956)

One of the most eminent theorists and important figures in the history of cinema, Robert Bresson contributed in various ways to the art of filmmaking, with the “actor-model” technique being probably the most notable of those. The technique indicated that the actors should restate their takes multiple times, in order to make any outward resemblances disappear, and achieve a subtle and true-to-self final performance.

As the title implies, the story is about the escape plans of Lieutenant Fontaine – a member of the French Resistance – from a Nazi prison during World War II, and is based on the memoirs of André Devigny (Bresson was also imprisoned by the Germans for over a year).

The actors in “A Man Escaped” are non-professionals (as it is almost always the case in this director’s works), and the overall focus is on simplicity and minimalism, yet the dramatic suspense (not the Hitchcockian type) goes side by side with a sense of redemption.

2. Paisan (Roberto Rossellini, 1946)

The second film of Rossellini’s “Neorealist Trilogy” is arguably the most distinct neorealist motion picture ever created, therefore had a strong impact on the careers of future filmmakers such as Gillo Pontecorvo, the Taviani brothers, and Matteo Garrone, among others (it was also cited as one of the all-time favorite films of both Federico Fellini – who was one of the screenwriters – and Martin Scorsese).

The movie consists of six completely unrelated episodes, all connected to the Allies’ Italian Campaign from 1943 to 1945, and written by six different writers the director himself handpicked.

All attributes of the Neorealist movement are highlighted to the maximum; the actors (who Rossellini coached several times during shooting) are all non-professionals, shooting is done on the respective location in Italy for each segment, and the whole story serves as a reflective representation of how WW2 was lived – as opposed to fought or portrayed in the history books – by everyday people and servicemen.

1. Kes (Ken Loach, 1969)

Arguably the most memorable of all the British New Wave “kitchen sink” dramas, Ken Loach’s second feature film is a one of a kind social realism classic set in the mining town of Barnsley, South Yorkshire.

Young David Bradley stuns with his performance as Billy Casper, a boy growing up in a fatherless dysfunctional family, whose daily routine includes reprobation and bullying intercourses, due to his slim figure and indifferent behavior. That partially changes when he captures and becomes emotionally attached to a kestrel, since that he finds a real interest in its training.

Loach’s choice of a regional cast – speaking the Yorkshire accent and dialects – and characteristic socialist approach achieves a faithful portrayal of the underpaid working class, and the rigid education system of the country.

Honorable mentions: Rome, Open City (Roberto Rossellini, 1945), La Terra Trema (Luchino Visconti, 1948), Umberto D. (Vittorio De Sica, 1952), Pickpocket (Robert Bresson, 1959), Il Posto (Ermanno Olmi, 1961), Salvatore Giuliano (Francesco Rosi, 1962), Au Hasard Balthazar (Robert Bresson, 1966), Putney Swope (Robert Downey Sr., 1969), El Topo (Alejandro Jodorowsky, 1970), Reconstruction (Theo Angelopoulos, 1970), Edvard Munch (Peter Watkins, 1974), Killer Of Sheep (Charles Burnett, 1978), Kaos (Paolo & Vittorio Taviani, 1984), Au Revoir Les Enfants (Louis Malle, 1987), Close-Up (Abbas Kiarostami, 1990), Children Of Heaven (Majid Majidi, 1997), The Wind Will Carry Us (Abbas Kiarostami, 1999), La Commune (Paris, 1871) (Peter Watkins, 2000), Sweet Sixteen (Ken Loach, 2002), Taxi (Jafar Panahi, 2015)

Author Bio: Andreas Papadakis has been a film lover for all of his life, but it is not until recently that he realized he had a desire for sharing his love with others through writing (hoping that the others will be ok with this). He enjoys a large variety of styles and genres, and he is in the process of creating his own screenplay in the near future, so beware… You can follow or friend him on Facebook.