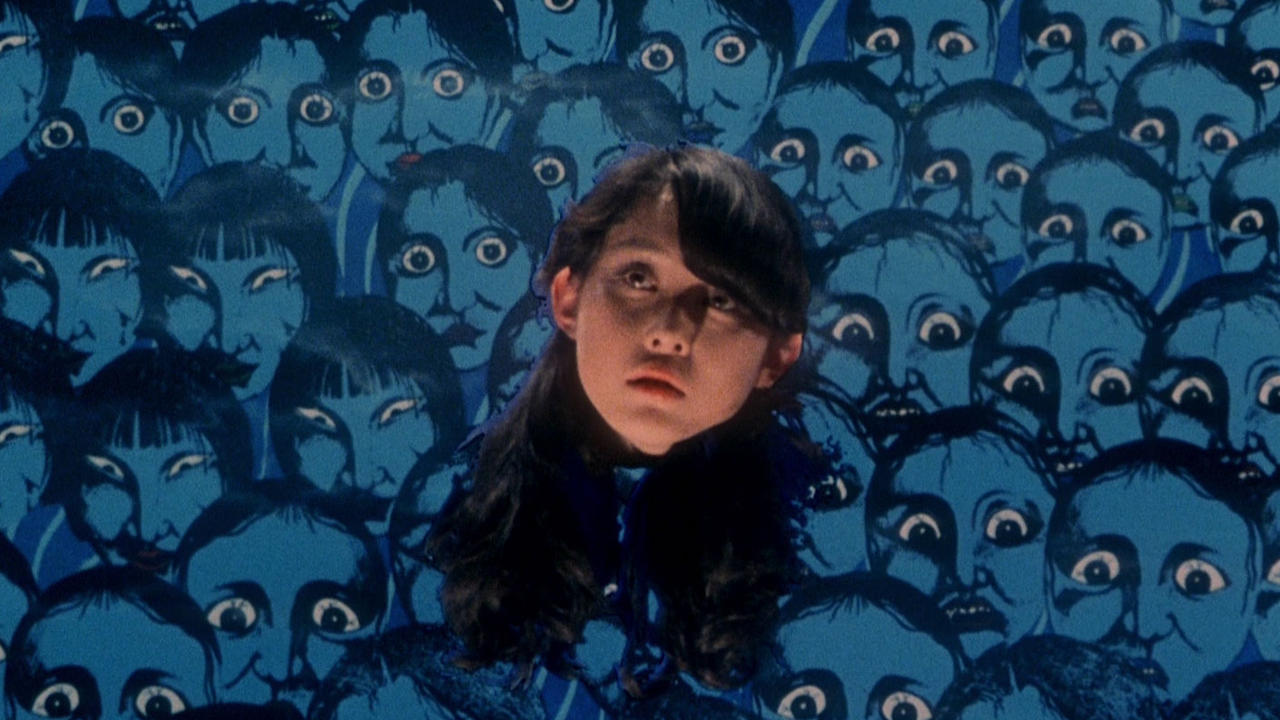

10. House (Nobuhiko Obayashi, 1977)

Probably the most incoherent entry on the list due to its surrealistic fashion, “House” derives from a script considered so absurd that at the time, no director would take it on in fear of ruining his or her career. Nobuhiko Obayashi, however, wanted to direct it since he initially read it, a plan he accomplished two years later.

The film revolves around seven girls who visit a house during their summer vacations, which is proven to be a living entity, as it kills the girls in the most absurd fashion.

Obayashi creates a perverse and ingeniously maladjusted interlude that barely fits into the cinematic frame, and constantly transforms from a supernatural thriller to a slapstick comedy and vice versa, where the special effects “flirt” with drollness, due to their absurdity.

9. Suicide Club (Sion Sono, 2001)

In one of the most notorious scenes in cinematic history, 54 female students jump over the rails of a train station in front of the incoming vehicle and bathes the terrified onlookers in blood and body parts. This is the first in a series of group suicides taking place all over Japan, of which three detectives are attempting to investigate.

In this first part of a trilogy that was never concluded, Sion Sono directs a harsh critique of contemporary Japanese society. He highlights the fact that technological advances and the influence of the media have depleted Japan of social values and standards, in favor of cruel commercialization.

The outcome is utterly pessimistic and disturbing. At the same time, through the depiction of violence involving the suicides, he successfully combines the crime and horror genres without having to resort to the supernatural.

“Suicide Club” introduced Sono to the international film scene, establishing him as one of its most promising filmmakers. It was screened in festivals all over the world, gaining status for the aforementioned scene and the controversial main theme.

8. Perfect Blue (Satoshi Kon, 1997)

“Perfect Blue” was initially meant to be a live-action TV series, but after the Kobe earthquake in 1995, the production studio suffered extensive damages resulting in budget cuts, up to a point that solely allowed the shooting of an OVA. Nevertheless, even though the shootings were roughly half-completed, Madhouse decided to distribute it as a feature film.

Mima Kirigoe, a member of the largely popular J-pop band Cham, announces during a concert that this will be the last performance of the band, since she has decided to pursue an acting career.

The announcement creates chain reactions in Mima’s life, as much as in the lives of the people close to her. A number of her fans become frustrated, regarding her decision as a betrayal toward them, mostly by a known stalker of hers named Me-mania.

In the meantime, she discovers a blog depicting details of her everyday life, which no one aside from her could experience. Additionally, the blog is updated on a daily basis, presumably by her. She discusses the issue with her manager, who soothes her for the time being; however, as she delves into the blog, she begins to lose her touch with reality.

Furthermore, someone is murdering certain individuals who had helped her with her career. Moreover, she is constantly discovering elements that incriminate her.

Kon focuses on the association between reality and presumed reality, using the archetype of the pop idol as an example. The actual personality of the artist is in contrast to the personality the fans witness, which is the one that becomes apparent on stage.

According to Kon, cinema can undermine reality, revolting against the human mind that almost exclusively receives images from the actual environment. The question he presents is clear: why should an image emerging from facts in the material world be truer than one emerging from the human mind? Kon’s Weltanschauung, which is present in all of his films, resides upon this particular questioning.

7. The Inugami Family (Kon Ichikawa, 1976)

Based on Seishi Yokomizo’s novel, “The Inugami Family” is a unique entry on the list, as it combines elements of drama with horror notions, creating a unique and highly influential film in the process.

When nabob Inugami Sahei dies, he leaves his fortune to Tamayo, a woman with no relation with the family, on the condition that she marry one of his three grandsons. His will results in a blood feud among the members of the family, as they turn up dead, one by one. Furthermore, when Detective Kosuke Kindaichi comes to investigate the case, the onerous past of the family is revealed.

Kon Ichikawa directs a film that starts as a dark and adult-themed family drama, but eventually becomes a horror movie as gore suddenly and unexpectedly makes an appearance. “The Inugami Family” also features magnificent visuals, benefiting the most from the fast editing and the set design that accurately portrays the post-war setting.

6. Onibaba (Kaneto Shindo, 1964)

In 14th century Japan, a man is forced to enlist the army, leaving his wife and his mother alone in their house in the swamp. In order to survive, the women ambush passing soldiers, kill them, and subsequently sell their belongings to a greedy merchant. Nevertheless, the wife initiates an affair with a deserter, enraging her mother-in-law who no longer trusts her. Things take a turn for the even worse when a mask stolen from a murdered samurai proves to have a demon residing in it.

Kaneto Shindo shoots the film exclusively in a swamp, where the protagonists live their own hell. Water, canes, and mud constitute an environment that, when combined with the black-and-white cinematography and the long, internal pauses, results in a silent nightmare. Shindo presents a movie concerning the worst of human instincts and an apparent message: the sole hell is the one human beings live in.

5. Pulse (Kiyoshi Kurosawa, Japan, 2001)

The script of the movie consists of two simultaneously unreeling stories.

In the first one, four friends, Kudo Michi, Sasano Junko, Toshio Yabe and Taguchi, are employed in a greenhouse. The latter, who is working on a computer program, suddenly disappears. Michi finds him in his apartment, but his demeanor is quite distant. When she looks into the next room, she finds Taguchi hanging and realizes that what she saw earlier was his ghost. Investigating the reason for his suicide, the remaining three friends decide to examine his program.

In the second story, economics student Ryosuke Kawashima surfs the Internet for the first time. When he does, his computer automatically directs him to a web page that shows photos of individuals sitting in dark rooms.

There is a definite allegorical element in the film regarding the alienation of individuals in an urban environment, leading to depression and suicide, specifically in Japan. The director, Kiyoshi Kurosawa, presents his trademark “slow-paced terror” style, which has its roots in “The Ring” but ultimately goes in a direction toward social drama, creating a very different film.

“Pulse” established Kiyoshi Kurosawa as one of the masters of the J-Horror genre and it’s considered one of the scariest films ever made. It was screened in festivals all over the world, including Cannes, and in 2006, an American remake with the same title premiered in the US, later spawning two sequels.

4. Tetsuo (Shinya Tsukamoto, 1989, Japan)

A car accident victim sticks a metallic tube in his thigh, an impulse after which his body is taken over by metal. Something similar also occurs with the perpetrator of the accident, and the action begins. Women raped with metallic phalli, sex with penises in the form of electric drills resulting in murder, hunting in dark corridors, bodily fluids, and a final confrontation between two beings that are more machine than human, are only a few of the grotesque spectacles in “Tetsuo”.

Shinya Tsukamoto used a 16mm camera and shot, in true guerrilla fashion, a black-and-white film that looks like a nightmarish video clip, an outcome intensified by the extreme noise music and the restless movement of the camera. The message concerning technophobia and the loss of humanity for the sake of technology is evident. However, even more apparent is the fact that the director aimed to shock through extreme violence, a purpose he completely fulfilled.

“Tetsuo” is clearly a low budget film; nevertheless, it established Tsukamoto as an international cult filmmaker, creating a unique style in the process, which was implemented in two sequels and in films like “Electric Dragon 80,000V”.

3. Strange Circus (Sion Sono, 2005)

Most of his fans thought that Sion Sono had reached his limits of the perverse with “Suicide Club”. However, they were in for a surprise with “Strange Circus”, which managed to combine elements of incest, rape, pedophilia, and transsexuality, along with many other taboos any regular filmmaker would never dare to touch.

Ozawa Gozo, a school principal, has modified a cello case, opening a peephole in it, and he forces his 10-year-old daughter, Mitsuko, to sit inside it and watch him and her mother, Sayuri, have sexual intercourse. In the beginning, his spouse does not realize the purpose of the case, but when she does, she’s unable to stop her husband from having his way with her. On the contrary, after awhile, Gozo begins shifting the two, having Sayuri watch him raping Mitsuko.

Later, the situation deteriorates further, since Mitsuko begins to enjoy having sex with her father and Sayuri gets jealous of her. This results Sayuri growing violent against her daughter when Gozo isn’t home.

Sono paints a canvas in blood red with some of the most extreme characters ever witnessed on film, with elements of the Grand Guignol theatre. He wrote an extreme and utterly surreal script, and even composed a haunting score to accompany his grotesque images. Additionally, the production design and the cinematography are quite artful.

“Strange Circus” is a cruel and arduous watch, but beneath it all resides a true cult masterpiece.

2. Audition (Takashi Miike, 1999)

Based on the novel by Ryu Murakami, “Audition” tells the story of Shigeharu Aoyama, a middle aged entrepreneur, who has recently lost his wife and has been living a disinterested life ever since. His 17-year-old son, Shigehiko, who worries about the turn his father’s life seems to have taken, prompts him to meet new women. Yoshikawa, a friend of Shigeharu’s and a film producer, proposes he to take part in a sham in order to meet women, and he agrees.

According to the plan, actresses would supposedly audition for the role of Shigeharu’s wife, in an imaginary film, although the actual purpose is for Shigeharu to find someone he could date. Many beautiful women audition, but there is only one that truly stirs his heart, Asami Yamazaki.

The young woman states that she is a former ballet dancer who was recently working for a music producer. Yoshikawa warns Shigeharu to be careful, since he was not able to cross check Asami’s background, but he is already blinded by love.

The film begins in the usual Japanese style, with hypnotic rhythm, scarce dialogue, almost no music, and permeating realism, both in the environment it takes place and in the characters. The first hour particularly does not look like a horror film at all, but rather like an indifferent social film.

Ηοwever, the actual and sole purpose of the rest of the film is to bring the spectator into a state of utter unpreparedness for the grotesque incidents that occur in its last part, that are as terrifying and perverse as one would expect from the onerous fantasies of both Murakami and Miike.

1. Ringu (Hideo Nakata, 1998)

Based on the homonymous novel by Koji Suzuki, this film was the one that turned the global audience’s attention toward J-horror, creating a franchise that spawned two sequels, three spin-offs, a Korean and two American adaptations.

The script revolves around a videotape that causes anyone who watches it to die in seven days. Journalist Reiko Asakawa and her ex-husband investigate the case, only to stumble upon Sadako, a creature with a sad and mysterious story who still exists somewhere between nightmare and reality.

Hideo Nakata presented a social message regarding technophobia and a fear of the media, while building a great story using horror as the main ingredient. Sadako’s exit from the TV is a clear example of the two, and is one of the most iconic (and horrific) images of the genre.

Author Bio: Panos Kotzathanasis is a film critic who focuses on the cinema of East Asia. He enjoys films from all genres, although he is a big fan of exploitation. You can follow him on Facebook or Twitter.