24. Ichi the Killer (Takashi Miike, 2001)

The leader of a Yakuza family disappears without leaving a trace and the rest of the gang members believe that he was murdered. Kakihara, his second in command and a schizophrenic, sadomasochistic misanthrope who is additionally in love with his boss, sets on a trip to exact revenge, which entails torturing other gangs’ members, an act he enjoys to the fullest.

However, the killer is not a Yakuza, but a disturbed individual, whose underlying, extreme violent nature is exploited by a mysterious persona, who eventually orders him to eradicate Kakihara’s gang.

Takashi Miike took the homonymous, overly violent manga and created one of the most controversial films of all time, due to its notorious characters, graphic depiction of torture and overall violence. Moreover, the film shocked the censorship committees to a point where they allowed only extensively censored versions of it, while Norway still forbids showing, distributing and even owning it.

Tadanobu Asano as Kakihara and Nao Omori as Ichi give two of the greatest performances ever in a cult film.

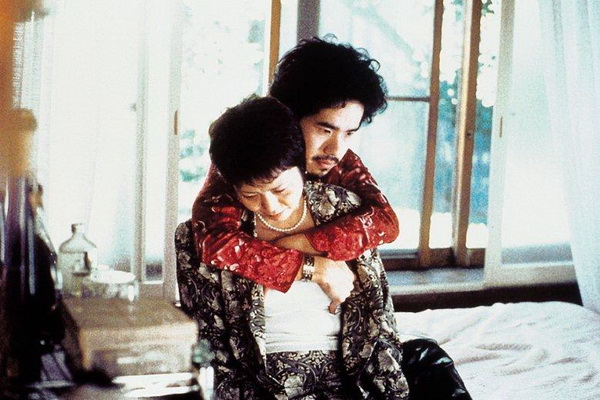

25. Visitor Q (Takashi Miike, 2001)

“Visitor Q” is a grotesque study of the human psyche, by a filmmaker who has transformed the rape of our aesthetics into his means of expression.

The script revolves around the Yamazaki’s, a family of four, all of whom are quite maladjusted individuals. Kiyoshi, the father, is a former reporter trying to shoot a documentary on violence and sex among youths. Therefore, he spends his time recording his son Takuya on camera, while his classmates bully him; he also occasionally has sex with his prostitute-daughter, Miki.

Takuya, frustrated by the constant bullying, takes out his fury on his mother, Keiko, beating her over any insignificant excuse, even in front of his indifferent father. Keiko finds solace in drugs when she is not prostituting herself. Eventually, an individual unknown to them establishes himself in their house, proceeding to subsequently torture all of them.

Miike included scenes of incest, fetishism and necrophilia in a film that sometimes functions as a perverse reality show about a family whose members act hypocritically normal, despite the various issues each one faces, at least until the visitor arrives.

His message about the contemporary Japanese family is clear: It is a dying institution that can only be saved by an extreme external force.

26. Suicide Club (Sion Sono, 2002)

“Suicide Club” was the film that established Sion Sono as a genuine cult filmmaker, chiefly for the introductory scene and the contentious subject it entailed. It was screened at festivals all over the world, gaining status for the aforementioned scene and the controversial main theme. The film spawned a sequel, a novel, and a manga.

At the beginning of the film, 54 female students throw themselves in front of an oncoming train, in a mass suicide that ends up in a terrifying bloodbath. At the same time, all the TVs in the city continuously show the latest video clip by the ultra-successful girl band Dessart.

Soon after the incident, a suicide wave seizes the whole country, with no clear intent. The police attempt to find the underlying cause with the sole evidence of two rolls made from hundreds of connected human skin pieces. At the same time, a girl whose boyfriend has also committed suicide tries to find a logical explanation.

Sono presented a new approach to the J-horror theme, by producing a terrifying effect without the assistance of the supernatural, simply by taking a social remark regarding technological advances and the influence of the media and taking it to its utmost extremes.

The “reality” of the film produces an outcome far more terrifying than the supernatural did, thus making films like “Dark Water” seem like child’s play.

27. A Snake of June (Shinya Tsukamoto, 2002)

Rinko is an employee for a psychological support phone line, who lives a mediocre, uneventful life with her husband who is obsessed with hygiene, a tendency that has led them into sleeping in different beds with a total lack of sex.

During the rainy season in Japan, Rinko receives an envelope by an unknown sender, which contains photos of her masturbating. A little later, the stranger calls her and blackmails her. What follows is Rinko roaming the wet streets of the city, blindly obeying the perverse orders of the blackmailer who guides her into a hurtful trip of sexual autognosis.

Shinya Tsukamoto toned down the element of violence this time, and instead focused on sex, creating a film that, using suppressed eroticism as a base, portrays a trip into the depths of sexuality.

He did not abandon his extreme cinematography style with the extensive use of handheld cameras, as he shot the movie in black and white and printed it in color film that created a distinct blue tint, which permeates the whole picture.

28. Flower and Snake (Takashi Ishii, 2004)

A remake of an equally cult production from 1974, which was based on the homonymous S&M novel by Oniroku Dan, “Flower and Snake” is basically a tale of a woman’s sexual slavery.

Shizuko is Japan’s best tango dancer and prized wife of a businessman named Ippei. The latter has money issues with the Yakuza, and their leader, who admires Shuzuko’s beauty, proposes to Ippei to sell her to him in exchange for his debts, and he agrees.

The rest of the film consists of Shizuko being subjected to sexual and emotional humiliation in front of a private VIP S&M show, which even shows the 95-year old boss who is connected to an oxygen bottle.

Takashi Ishii presents a stylish and shocking film that pulls no punches at all, since every perverse action is presented with utter detail and with the camera being very close to the “action”.

The film benefits the most from the presence of the gorgeous Aya Sugimoto, a former model and singer, who spends most of her time on screen naked, bound and humiliated, in this highly perverse and utterly misogynistic film.

29. Pussy Soup (Minoru Kawasaki, 2008)

This film could be characterized as cult just because it answers the question of where Minoru Kawasaki would go, after films like “The Calamari Wrestler”, “Executive Koala” and “Kani Goalkeeper”. And the answer it preposterously provides is “to cat-puppets with existential problems”.

Taisho is the aforementioned puppet who cannot live up to his father’s success and is in search of a purpose in his life. Initially he turns his attention toward sushi restaurants, an idea that fails because he cannot stop eating the fish. Eventually he finds his calling in the art of making ramen and after a number of years and some failures, he manages to open his own sushi restaurant with a regular following, and even makes a friend. However, his troubles are not entirely gone.

Not much more to say about a film regarding a puppet who contemplates suicide and deals with father issues, fame and the search for himself. Let’s just say that cuteness was never so paranoid.

30. Vampire Girl vs Frankenstein Girl (Yoshihiro Nishimura, 2009)

Monami is an adolescent vampire who roams the world with no purpose, apart from killing whomever she meets along her way. Eventually she arrives at a school where she enrolls as a student, and shortly after she falls in love with a classmate of hers named Mizushima. However, she does not notice that Keiko, another student and the daughter of the professor of physics and vice principal, is also in love with Mizushima.

The aforementioned professor, Kenji Furano, secretly conducts experiments in the school’s basement in order to build the ultimate human killing machine. For that purpose, he uses human parts from students his assistant and school nurse brings him after killing them. Furthermore, Monami tricks Mizushima and turns him into a vampire.

Nishimura’s regular though preposterous style of filmmaking found its apogee in this film, beginning with the title and continuing with every character, dialogue and notion presented in this nonsensical, anime-like and extremely violent film.

In that aspect, there is a female protagonist with superpowers that kill and maim at leisure, constant bloodbaths (where his prowess in the depiction of blood becomes quite evident), and some very impressive battles, despite their absurd depiction.

Furthermore, he manages to incorporate some social remarks regarding teenage suicide tendencies and Ganguro, in a satirical and generally non-serious fashion.

Author Bio: Panos Kotzathanasis is a film critic who focuses on the cinema of East Asia. He enjoys films from all genres, although he is a big fan of exploitation. You can follow him on Facebook or Twitter.