10. 2046 (Wong Kar Wai, 2004, Hong Kong)

Wong Kar Wai cooperated with Christopher Doyle in this film and, as usual in their collaborations, the result was magnificent. Doyle implemented a very impressive technique in this film by frequently using freeze-frames that occur midway through the scene, in an elaborate manipulation of film speed.

Another technique presented in this film is the one where a shot within a scene visually stands apart from both the preceding and following shots, depicting its own mood and emotions.

This method is evident in the scene where Bai Ling talks with Chow in her room after they had sex, which comprises individual shots where each actor faces right on the screen, despite the fact that they are actually opposite.

9. Oldboy (Park Chan Wook, 2003, South Korea)

Park Chan-wook has stated that the technical element comes second in his movies, with the first roles being reserved for the characters and the story. However, his films still entail elaborate cinematography, usually in an exploitation fashion.

One of his films that excels in this aspect is “Oldboy” where, along with cinematographer Chung Chung-hoon, he presents a number of scenes that are artful as much as they are grotesque. The one where Dae-su is eating a live octopus and the ending ones are distinct specimens, although the most memorable is the one where Dae-su fights a score of thugs in a narrow corridor.

The sequence is actually a continuous take that took 17 takes in three days to achieve the result Park wanted, and the result is truly magnificent. The geometry of it is astonishing and quite reminiscent of old school beat-em-up games, like “Final Fight” and “Double Dragon”, a sense that is heightened by the fact that the protagonist fights alone against scores of enemies.

8. Sansho the Bailiff (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1954, Japan)

One of the greatest films of both Kenji Mizoguchi and Japanese cinema, “Sansho the Bailiff” also features elaborate cinematography, which transcends the technical aspect by depicting images filled with symbolism and meaning, with the help of Kazuo Miyagawa, Mizoguchi’s regular collaborator.

As Mizoguchi’s style was deeply inspired by the composition and mood of traditional Japanese paintings, the motion in the film tends to appear vertically instead of horizontally, and frequently, even diagonally. The film also features the distinct, artful long shots of Mizoguchi, which aim at placing the characters within their symbolic environment.

The symbolism is also present in the movement, as movement to the left suggests backward in time, and to the right, forward. Upward movement suggests hope, and downward the opposite.

7. Pather Panchali (Satyajit Ray, 1955, India)

The first part of the “Apu Trilogy” is the first from independent India to attract major international critical attention; it won India’s National Film Award for Best Feature Film in 1955, the Best Human Document award at the 1956 Cannes Film Festival, and several other awards, establishing Satyajit Ray as one of the country’s most distinguished filmmakers.

The film features black-and-white cinematography from Subrata Mitra, a still photographer who did his first work in cinema on this film, even having to borrow a 16mm. Despite his inexperience, his cinematography is extremely effective, particularly in natural environments, like forests, rivers, in a pond, the monsoon, and more.

In particular, one scene stands apart, the one where the mother is watching over her feverish child, while rain and wind hit the small house from all sides, with the threat becoming evident from every aspect, in a truly agonizing sequence.

6. Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter… and Spring (Kim Ki-duk, 2003. South Korea)

Kim Ki-duk may be famous for his low-budget films and his tendency to shock through violence, but his films also feature wonderful cinematography, occasionally presenting images of great beauty.

A great specimen of this trait is “Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter… and Spring”, which features magnificent scenes of natural scenery, which transforms as the seasons pass, in one of Baek Dong-hyeon’s best works. In particular, the lake is depicted in all its glory through the seasons, with the ones during the winter, when it becomes frozen, standing apart.

The sequences where Kim, who actually plays the adult monk, is training in martial arts on the icy water, are probably the most beautiful in the film.

5. Hero (Zhang Yimou, 2002, China)

In one of the most visually impressive Wuxia films of all time, Zhang Yimou and Christopher Doyle present magnificent cinematography, chiefly through the explicit use of colors.

The various sceneries of the film are all wonderful despite their diversity, since the film includes shots in the desert, in a lake, in the forest, in a temple, and in the king’s palace.

The elaborateness of the cinematography becomes even more evident in the magnificent action scenes that occur in the aforementioned settings and with the use of meaningful pauses and impressive slow motion.

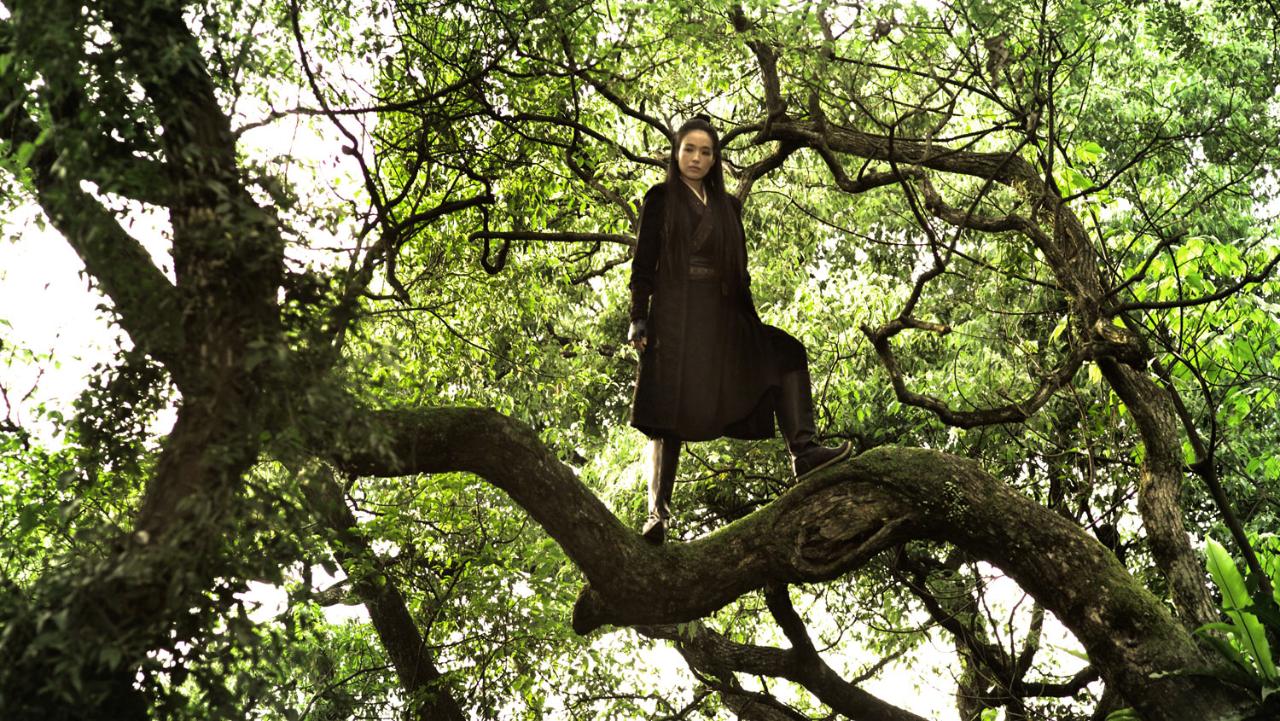

4. The Assassin (Hou Hsiao Hsien, 2015, Taiwan)

Hou Hsiao Hsien took a chance in Wuxia, in a film that spawned controversy, particularly among fans of the genre, but was undeniably gorgeous, with Hou and Mark Lee Ping Bin proving their prowess once more.

Hou’s distinct long shots and long takes are present once again, with the purpose of depicting in detail the natural environment where the story takes place. Furthermore, the film features images of rare beauty, either in the impressively colored interiors or in the woods and rooftops, with the focus usually being on the sentiments and thoughts Shu Qi emits through her silence.

The film is shot in old-fashioned 4:3 ratio, which only opens for a few significant shots. Probably the film’s best scene occurs in the woods, where an impressive sword fight is observed outside the forest, through branches and shadows.

3. Rashomon (Akira Kurosawa, 1950, Japan)

With this film, Akira Kurosawa actually wanted to make a tribute to silent films, and as silence takes over large parts of the movie, the focus on cinematography is even greater than usual.

The most obvious trait of Kurosawa and Kazuo Miyagawa’s shooting is the elaborate use of natural light, as exemplified in the scene in the woods, which was, additionally, the first time someone shot the sun. As it is shown through the thick branches, with the camera turned upside down, its depiction is as obscure as the way the truth is presented in the film.

Furthermore, in that particular sequence, the woodcutter’s movement is depicted as both from left to right and right to left. This tactic is a metaphor for the case the film deals with, where nothing is predetermined or certain. As the woodcutter’s movement differs according to the point of view, the same applies to the case. The sequence in the forest is considered among the greatest moving camera shots in the history of cinema, as it combines technical prowess with heavy symbolism.

2. Ugetsu Monogatari (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1953, Japan)

This film is probably Kenji Mizoguchi’s most celebrated, and is considered a definitive part of the Golden Age of Japanese films. Furthermore, some of his most renowned scenes are included here, with the help of cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa.

The first of those scenes occurs in the very beginning of the film, as the camera pans across the landscape, in the fashion of traditional Japanese scroll painting, in one of Mizoguchi’s most distinct characteristics.

The second and most famous one is the scene in the lake, where in a place filled with fog and mist, a lone boatman emerges to warn the protagonists of pirates. The scene was partly shot in a tank with studio backdrops, but the cinematography and motion is so perfectly implemented that the scene looks 100 percent natural.

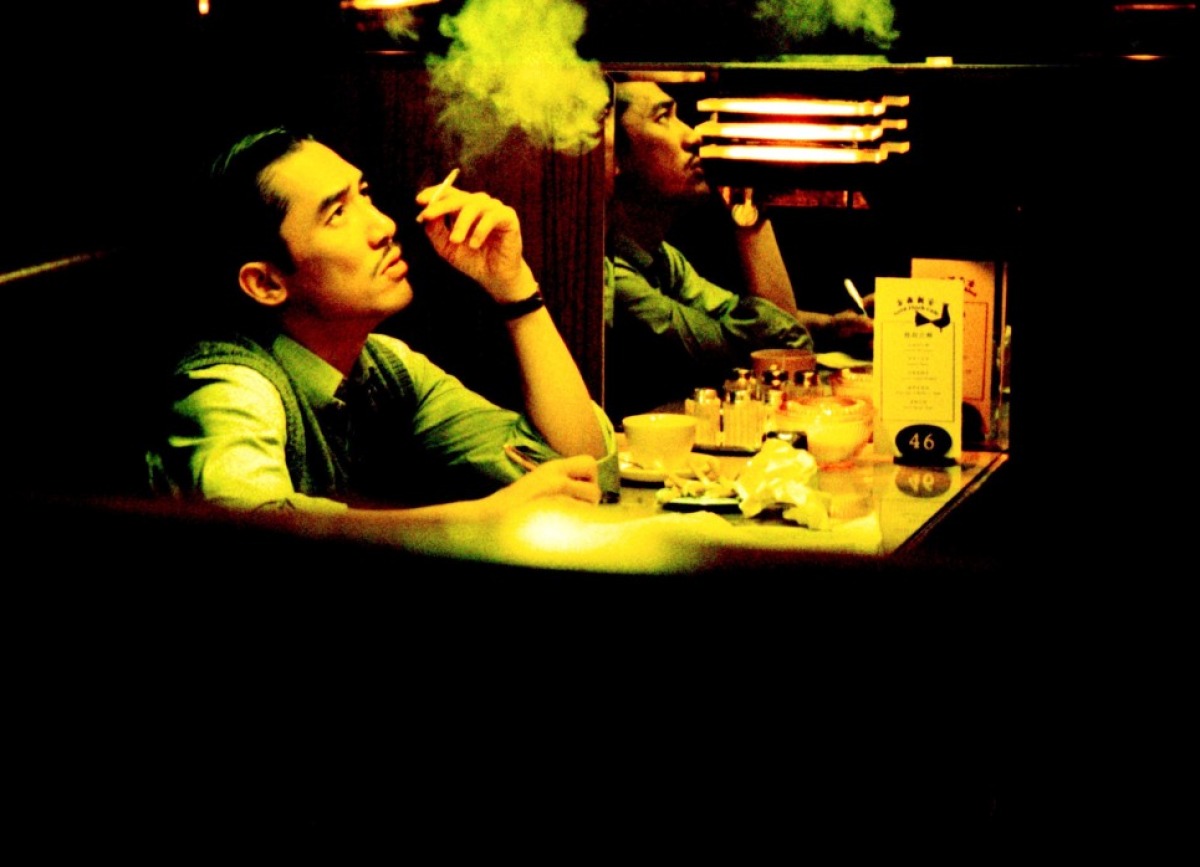

1. In The Mood For Love (Wong Kar Wai, 2000, Hong Kong)

In this film, Wong Kar Wai cooperated with probably best the best two contemporary cinematographers in Asian cinema, Christopher Doyle and Mark Lee Ping Bin, resulting in a true visual masterpiece.

The three of them used the camera in a way that gives the audience the sense that they are in on the action while focusing on the protagonists’ every move and look, through the extensive use of slow motion. These two tactics are exemplified in the scene where Su Li-zhen and Chow Mo-wan are sitting together, waiting for the rain to stop, and the one in the end, where Chow is whispering in a hole in the wall of Angkor Wat.

Author Bio: Panos Kotzathanasis is a film critic who focuses on the cinema of East Asia. He enjoys films from all genres, although he is a big fan of exploitation. You can follow him on Facebook or Twitter.