Pedro Almodóvar has been a mainstay of Spanish cinema for the last 30+ years, emerging in the years after General Franco’s death and the country’s shift towards democracy.

He has in that time period been perhaps the only Spanish director to have achieved and maintained a sustained period of commercial and critical acclaim worldwide, with each new film of his an event amongst cinephiles almost everywhere (notwithstanding a few pernickety naysayers) – a problem that is likely to do with the pot-luck of cinema distribution deals than with any particular deficiency on the part of Spanish filmmakers.

Broadly, his career can be split into two main phases: the bawdy transgressive sexual comedies and farces of his early years (stretching from his first feature film Pepi, Luci, Bom and Other Girls Like Mom in 1980, up to Kika in 1993), and the subtler, narratively complex high melodramas of his later years (The Flower of My Secret in 1995 to the present day).

Both sections of his career share broad interests thematically, though they tackle them in different ways, and there is a clear difference in the way Almodóvar crafted his films in the early days, and how he crafts them today.

Of course, he didn’t stick to one genre in either phase either; one of his greatest early films, The Law of Desire (1987), engages with sexual and gender identity amidst a burning romance as if it were the kind of melodrama that would make statues melt, and would fit snugly between All About My Mother (1999) and Talk to Her (2002) were it released then.

His most recent film I’m So Excited (2013), whilst rather unfairly dismissed by most critics, would likely be nearly as applauded as Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (1988) were it released back then.

Granted, whilst Almodóvar has enjoyed more international critical success during the second phase of his career, it shouldn’t stop those interested in his work from venturing into his early material.

The earlier films have a remarkable depth to them that is occasionally obscured by their sheer energy – one can palpably feel the exhaling of Spain’s creatives, outcasts, and misfits all at once after Franco’s death. What lies beneath that exhale? What concerns separate Almodóvar’s cinema from those of others?

A heads-up for any readers, there will be a section on sexual violence. Not overly in-depth, but there nevertheless.

1. Fluidity of identity

Perhaps the single most common theme in Almodóvar’s cinema is the fluid identies of his characters. There are no set stereotypes about people in Almodóvar’s world, and even if such stereotypes do appear they are used primarily to make a wider point.

The two leading men in Talk to Her, Benigno and Marco (Javier Cámara and Darío Grandinetti) both take on roles that, for the most part in a male-dominated world, are considered to be feminine.

They dutifully take care of the women they love, both of whom are in comas, subsuming themselves entirely to the needs of the women for better or for the tragic worse, in effect taking on the emotional heavy-lifting that women have traditionally done in relationships.

They reject most of the classic ‘Hollywood’ notions of what leading men ought to be and behave like, and the notion of crying during a theatre play is perfectly normal. Their identities therefore, are not rooted in traditional notions of masculinity or femininity, but rather ideas of what they believe is best for those they love.

Similar themes occur in All About My Mother; Manuela (Cecilia Roth) watches her son, Esteban (Eloy Azorin), get killed in a car accident trying to chase down his favourite actress Huma Rojo (Marisa Paredes).

Looking to inform Esteban’s father, she travels from Madrid to Barcelona, along the way tracking down her old friend Agrado (Antonia San Juan), a transgender prostitute. Much of the film is spent talking about Esteban’s father, who, in the intervening years has become a woman, Lola.

Ultimately, All About My Mother is a film all about people whose identities are always in flux – take for example, the nun Rosa (Penélope Cruz) who bears Lola’s child, a supposedly celibate religious figure who is entirely at ease amongst those whom the Catholic church hasn’t necessarily always been kind to – but their identities never overtake the love and empathy they have for one another as friends and family.

Roger Ebert perhaps said it best when he wrote: “though two of its characters are transvestite hookers, one is a pregnant nun and two more are battling lesbians, this is a film that paradoxically expresses family values.”

We see repeats of this theme almost everywhere. It’s apparent in Matador (1986), Law of Desire, Bad Education (2004), Volver (2006), Broken Embraces (2009), and The Skin I Live In (2011), to name just a handful.

What emerges is a portrait of people, complex people who respond to their own situations in their own ways. Their own selves change as life etches its experiences on their bodies, their being constantly in flux against the outside world and its strictures.

2. Flippancy over identity

Here’s a question: what unites The Danish Girl (2015), Dallas Buyers Club (2013), A Single Man (2009), and just about any other LBGT-themed Hollywood film? That’s right! In each one, LBGT characters are forced to suffer for a pre-determined period (usually 75% of the film’s overall run-time), all in the name of gaining acceptance for their sexual preferences or gender identity.

Truth be told, many of these films in and of themselves aren’t bad (I personally have a big soft spot for Dallas Buyers Club, in spite of its flaws), but the trouble is that this appears to be the only type of LBGT film that Hollywood is capable of producing, even when such films are led by LBGT people, as in the case of the director of A Single Man.

Considering that there are filmmakers like Gregg Araki (whose body of work is severely underrated but extremely brilliant) and Sean Baker (whose 2015 film Tangerine made waves across the festival circuit last year) who are working even within LA and producing brilliant, positive LBGT-themed films without a second thought, it’s quite depressing that the only films that get major distribution deals are those in which people are marked out by their sexual orientation and then made to suffer.

Step forward Almodóvar. Few characters in his films ever even find their gender or sexual orientation being commented on let alone questioned – and all this in 1980s, post-Franco, staunchly Catholic Spain. Carmen Maura in The Law of Desire plays a trans woman.

Nobody, not even the bumbling policemen she deals with at one point, questions this fact and they take it at face value, and the same goes for the film’s homosexual main characters.

The question of Lola’s gender in All About My Mother is similarly never bought up, with the drama focusing rather on her irresponsibility regarding childcare and drug use, and again neither Agrado’s gender is ever in question; instead it inspires attraction and empathy from those around her rather than hate or ignorance.

In Kika, the titular character (Verónica Forqué) starts an affair with two men at once, but this causes relatively little drama in the overall context of the film, as does her maid’s (Rossy de Palma) frequent declarations of love for her.

Summarily, the question of who you prefer to have sex with and who you would rather be is always taken at face value in Almodóvar’s films. His characters do go through their own hardships, but it is extremely rare that these hardships emanate from their own identities or sexual preferences. Who you are is not in question.

It is how you are that is important. It’s a refreshing state of affairs compared to Hollywood. When Hollywood produces a film based on gay characters, it is marketed as a gay film. When Almodóvar does it, it just a film, and all the better for it. Maybe in the future, this won’t even be an apparent theme in Almodóvar’s work. Maybe.

3. The act of performance

Overlapping with that centralising theme of identity in Almodóvar’s films is the very act of performance. Not only are his character’s identities always in flux, they are also very often consciously performing roles to suit their needs and the expectations of those around them. They take on the characteristics of an identity and perform them.

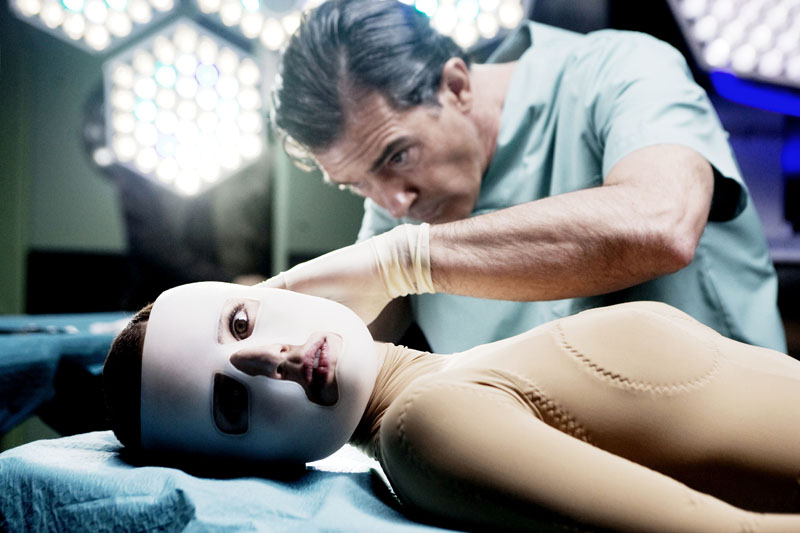

The Skin I Live In is a prime example of this, and without wishing to give too much away of the film’s labyrinthine plot, much of it functions around Vera (Elena Anaya), a woman we find is held captive by Dr. Robert Ledgard (Antonio Banderas) and who looks identical to his dead wife, learning to gain his trust by being his dead wife. By subsuming herself into that role and morphing into someone else, she gains her freedom.

Elsewhere in Broken Embraces, a similar act occurs. Lena (Penélope Cruz) starts an affair with the director Mateo Blanco (Lluís Homar), unbeknownst to the film’s producer and her lover Ernesto Martel (José Luis Gómez). We see Lena make passionate love to both of them, but after the latter has finished, she hides in the toilet to puke.

Again, it’s an act of performance within the film, a method of surviving until the time is right for the truth to be uncovered or for freedom to be bought, a method of keeping some form of the status quo afloat until the dislocation between reality and performance is too much to bear.

It’s no surprise that in a scene where Mateo is making decisions about Lena’s ‘look’ and makeup for the film, the makeup artist dresses her hair in various ways that reflect the great Hollywood actresses of yore – Marilyn Monroe, Lauren Bacall, Rita Hayworth, and the like – and eventually Lena’s look for the film is settled: Audrey Hepburn.

And what an Audrey Hepburn she is! The scene acts as a meta-comment of the nature of performance both in cinema and in reality. Most of us know these actresses purely through their screen presences.

They had a charisma and power onscreen that went beyond mere physical beauty and was to be found somewhere in the transcendence. Think of the way Monroe simply burned up the screen in her first appearance in Some Like It Hot, or the way Bacall gazed sultrily at Humphrey Bogart in To Have and Have Not.

These were actresses that never looked like they were acting, they just were on that screen. Yet that in itself was a performance, their private lives a world apart from who they were onscreen. Cruz herself has some of that same power and gravitas, the same ability to draw the entire room with a glance or a look.

Almodóvar’s films are full of these people, even if they don’t conform to traditional beauty standards: it is hard to think of many actresses with as much gravitas onscreen as Rossy de Palma, a regular supporting character in Almodóvar’s work.

4. Brechtian distancing techniques

In conjunction with the act of performance, Almodóvar loves using distancing techniques that make one aware of the inherently constructed, contrived, and fictional nature of cinema.

One of the most frequent criticisms levelled at the director is that his work is overly-convoluted, and that his byzantine plots often rely on bizarre coincidences and contrivances, but this is an observation worthy of people whose lives revolve around missing the wood for the trees.

The sheer preposterousness of Almodóvar’s plots serve as his way of shifting elements around to provide us, the viewer, with a through-line to the central subject of his films, whether it is the discussion of care, friendship, and obsession that characterises Talk to Her, or the madcap satirisation of modern media and its subliminal encouragement of voyeurism in Kika.

Almodóvar’s films are filled with people watching others, with screens, with voyeurs. Everyone records, and so do we, in our own memories. One of the opening scenes of All About My Mother is a startling case in point. After we are introduced to Manuela, a hospital nurse, we see her acting in an instructional video for trainee doctors when dealing with organ donor cases.

It’s a convincing performance, but we are told from the start it is all a fake. Later, she has to play the scene again for real when Esteban dies, and the viewer is partially left wondering if what we are seeing is a reality or not.

Almodóvar loves reminding the audience they are watching a film. However, he is careful not to break the immersion with quirky meta nods and winks to the camera; his cinema is rooted in his characters and their actions, but Almodóvar clearly wants us to step back and consider what it is they are doing and what the implications are, in a manner that would make the legendary German theatre director proud.