It’s difficult to characterize the cinema of the Coen Brothers, since their influences are so many; they’re able to manifest a kaleidoscope of different moods in a masterly way. The task we’re going to encompass is much more wide than what I expected.

The first point we suggest considering is in regards to their subterranean message: the failure of an American dream. In a certain way, their masterpiece, “The Big Lebowski”, is the perfect example of this giant failure.

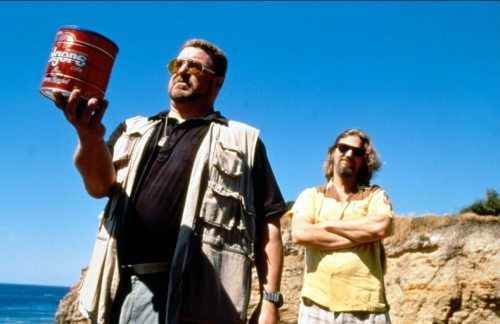

The society depicted in Lebowski’s Los Angeles is a late-capitalist America where the gap between the poor and the rich is so wide, and the plot is a perfect example. But we’re not talking only about spacial categories; LA is no more representative of the wild unexplored America, but rather it is the perfect example of the last crucible. Ironically, there’s also a contraposition between the voiceover made by The Stranger, an iconic cowboy and an icon of exploring the US, and on the other side, there’s The Dude.

“The Dude is no Great American Dreamer (or achiever – the Stranger calls him “a lazy man”); he’s just a nameless, impoverished, collapse of a man. And Los Angeles is the proper place for this man because it is the antithesis of the open frontier that might generate the Great American Dreamer.

It is, as mentioned, the very end of the twentieth century (the American century), and at this time and in this place, the Dude shows us that the potential for greatness is limited and shrinking fast.“ (DA, p. 180)

So, the LA in “The Big Lebowski” is a postmodern one, and the setting is firstly very 90s. But, apart from the setting, the importance of the social aspect is underlined by the comparison between the Dude and the Big Lebowski. Those two big and contrasting aspects of a capitalist America have revealed both of their failures. A failure confirmed also by the omnipotence of money toward all the characters.

“Although the American Dream is clearly suffering systematic and ideological failure, Americans still hold on to it: the Dream abides. […] The shrinking of the middle class means that there are relatively more “idle rich” and significantly more struggling poor. Without the model of the “productive middle class”, the Dude has no example of hard work and fair play, so he just steals what he wants, or thinks he deserves. The Dude’s rug shows that there is all but total corruption of the American Dream but, again, Americans still hold on to it. It is as if the American Dream stills ties us all together, regardless of the fact that we find evidence everywhere that it no longer works.” (DA, p. 184)

In his article, Todd Comer explains that The Dude is heroic, but probably there’s a Cartesian “I” that represents a real hero. Jeff Bridges, in this situation, is against the hero and the archetypal Cartesian “I”. The form of heroism displaced by The Dude is purely casual, and only by considering the socio-political ambient we can understand it better.

Todd Comer continues sustaining that the Gulf War, and more generally the War context fits perfectly the “Walter” character. While the Dude is frequently a “passive” speaker in the film, Walter is active, like a counterpart.

“In the case of the Dude’s pacifism, the painful fact is that his presence does not hinder violence. Instead, the Dude is complicit with the violence that kills Donny. […] The Dude is complicit in this violence because he represents no difference to the homogeneous world of Walter. Walter, in this case, needs to be understood as an exemplary “rational” subject. By rational, I mean to suggest that Walter’s assimilation of the world is both self-interested and economic: everything that is different must be made sense of and be “fashioned” to stabilize the self. […] In such a solipsistic world, any effort to dissuade a character like Walter from action is an immediate failure, since rationality violently assimilates such disruptions.” (TA, p. 102)

The film recalls a nexus between myth, narrative, and consciousness, all linked to violence. Donny represents the nonsensical third referee to the conversation between Walter and the Dude. At the end, the second one finishes to support the first one in his violence. The strange fact is that they are opposites in an ethical first position, but through his non-action, Lebowski sustain Walter’s final ethos.

The Nihilists scare both of them, but from a certain point of view, the Dude could also be seen as a nihilist. A necessary distinction needs to be made: there’s a clear difference from the Coen’s perspective and their singular characters. We will never know if the directors’ ethical perspective is on a meta-level, or if there is a correspondence to The Dude or Walter. We can see the film in this way:

“The Big Lebowski shows us that we are all failures, sinners, in one way or another, and it is the Dude who constantly reminds us that life in America is filled with “strikes and gutters, ups and downs,” “lotta ins, lotta outs, lotta what have yous.” Even though the whole of The Big Lebowski has been fraught with tension, with anxiety, cynicism, and bitterness, it ends happily – optimistically, even – with the Stranger hoping that the Dude and Walter make it to the finals of the bowling tournament, and telling us that there is a little Lebowski on the way. These are hallmarks of absolute success (reaching a threshold of well-being higher than where we started) and absolute success is possible for most of us. The Dude abides; he accepts this measure of success” (DA, p. 192-193)

It’s curious that from a martial myth sustained by Walter, on the opposite we can find, following Comer’s thoughts, a castration complex in Lebowski’s dancing visions.

“Instead of a traditional erotic figure wearing suggestive clothing, we see a figure costumed as a Valkyrie – armor and all. “Gilda” has been transformed into Maude, the feminist. Ultimately the dream/dance sequence blurs into castration anxiety.” (TA, p. 108)

It’s difficult for the spectator to notice the voyeurism that Comer underlines in the Corvette’s destruction sequence and some fragments before. Why voyeurism? Because the spectator identifies itself with the male main character, and in this particular scene, that is Walter. A dominator against a little kid (Larry); here a misunderstanding leads the entire situation.

“… if conversation operates as myth to create a unitary consciousness, Larry’s radical disinterest in Walter (due to exposure to his father’s illness) leaves the substance of this myth hanging. The breakdown of the narrative means that the narrative borders have momentarily dissolved and the narrative “self” (and those selves that it limits) has spaced out and into the other. However, this interruption ripples throughout the film. Since the film opens and closes with a famous western actor (The Stranger) it can be seen as striving toward a traditional cowboy western narrative only to fail because the origin – writer Sellers – lies gasping in an iron lung, incapable of speaking and making his narrative cohere. Once again: the death of the other overwhelms the capabilities of the rational subject as well as the subject’s myths. The Big Lebowski is postmodern in the sense that it shows us not only the death of the poet, a writer of Westerns and, in a way, of Lebowski, but also the unworking that results.” (TA, p. 110)

Walter’s way of understanding the of plot of “The Big Lebowski” is mainly based on patriotic visions. Such a vision is fulfilled with brutalities of war and consequently we can find a form of violence, hidden psychoanalytically, under Ego’s surface. The “I”, the hero, is only a face of the medal. We have a second leitmotiv that leads Walter’s actions.

“Walter’s obsessive assimilation makes sense against such a backdrop. In this scenario, not only are there dead soldiers, missing prisoners of war, but also an entire war that never properly found subjective closure. That (lost) war remains for him a wound that requires perpetual care. The strangely poetic eulogy given at Donny’s funeral is the summit of such ontologizing. Donny’s death allows Walter to relive his experience of combat, death, funeral rites to be performed. This is crucial because it allows him to simulate the Vietnam war and right it.” (TA, p. 112)

There’s a convergence of myth failures in the Lebowski’s character. In Coen’s cinema, apart the demythologization of “The Big Lebowski”, we can find also the end of a dream in “Raising Arizona”. In those two movies, from a certain point of view, we can see the characters “reduced” to their stereotypical visions. The spectator will find their reactions ridiculous and comic, at the limit of absurdity; the Coens like to let us think to our human primordiality.

This form of annihilation destroys every social and cultural reference, taking it to its endless limit, and we’re like primates. This cultural reduction lets us face off a giant quest: “Where is our God now?” Retracing Job’s quest in the Old Testament, we’re like primates facing an inexplicable evil but today, with a nihilist face. Inside this vision, always considering our little existence, we can rethink the entire cinema of the Coen brothers.

In a lot of their movies, we can see characters “reduced” in various manners, but it’s clear that characters are victims of a bigger destiny. A giant god-like hand of doom is always tracing their path to the blackest end.

We can see the ironic twisted plot in “Burn After Reading” or the odyssey (who’s more victim of faith than Odysseus?) in “O Brother, Where Art Thou?”. But “A Serious Man” is probably the movie where they underline this perspective better; the protagonist abides every event with a sort of Job’s verve.

There’s a kind of red rope that guides us in the Coen’s labyrinth; from their first period (“Raising Arizona”), through the years (“The Big Lebowski”) until now, they always try to say something to the spectator. You’re nothing more than a human. At the end, humans, in their difficult periods, like to bow toward an altar, and Dostoevsky knew this perfectly.

Coen’s cinema is something like a theodicy, and you can have the impression that they love to remind us of the link between God and evil. But in their irony, completely absent in the book of Job, we can feel the suspect that they’re saying to us: you are bowing to an empty altar, almost as though God has forgotten us.

In that case, what’s the point? Start from this Pascalian question: since you’re an insignificant little human facing a giant hand of doom that leads your life, a lot of times to a bad gateway, you should ask yourself: where’s your God now? Through their movies and their characters, the Coen brothers let us think to a never-ending metaphysical quest, which we can revive with Psalm 42.

But we can remember also this: the Dude abides.

References:

DA : ShaunAnne Tangney, The Dream Abides: “The Big Lebowski”, Film Noir, and the American Dream, «Rocky Mountain Review», Vol. 66, No. 2 (Fall 2012), pp. 176 – 193

TA : Todd A. Comer, “This Aggression Will Not Stand”: Myth, War, and Ethics in “The Big Lebowski”, «SubStance», 107 (2005), pp. 98 – 117