5. Trainspotting (1996)

Danny Boyle was only on his second film when he became an internationally beloved filmmaker, with his rapid twisting through the messy entrails of his narratives, never stopping for a breather.

He produced cinematic adrenaline, barely letting us stop to allow audiences to register what they’ve seen on their screens. And the result? A film that’s exhilarating to watch and lingers in your memory, both intellectually and emotionally.

Another film that takes many liberties from its source material, the novel “Trainspotting” by Irvine Welsh (who has a small but hilarious role in the film) focuses on a much larger collection of characters in their drug induced euphoria turned manic self-destruction.

However, the film narrows down to Mark Renton (Ewan McGregor’s most complex and brilliant role), Sick Boy (Jonny Lee Miller), and to an extent Spud (Ewan Bremner). However, what the film does is not necessarily a bad thing; it makes it much easier to follow, while the singling out of its three leads allows for a deeper study into the individuals, rather than the book’s focus on addiction, and becomes a researched and intriguing look at the unique effects of heroin on individuals in society.

Many claimed the film glorified the use of drugs, but upon my own viewing, I saw nothing that could ever possibly be appealing. In fact, the moment that sticks out most is a surreal experience with “Scotland’s worst bathroom,” which one would imagine could turn off any viewers from thinking Boyle saw positives about heroin addiction.

4. American Psycho (2000)

A controversial film spouted from a controversial book, “American Psycho” would foreshadow the next decade’s rampant breaking down of cinematic barriers, heralding a decade of disaffected viewers with director Mary Hanson’s glorious gory yuppie satire.

Patrick Bateman, a successful and wealthy stockbroker, leads a narcissistic and hedonistic lifestyle dictated by cocaine, prostitutes, expensive meals, and murder, while his yuppie friends carelessly lead similarly excessive yet less psychopathic lives oblivious to Bateman’s… “discrepancies”.

Bret Easton Ellis was projected as a “voice of the new disaffected youth” with his first novel “Less Than Zero” and would soon become one of the most threatened novelists in history with his third work, a slasher, horror, and American Dream satire all rolled into one, and although an adaptation wasn’t released until 2000, there were attempts to bring it to life for more than 10 years.

Hanson wisely prevented a profit-threatening X rating by removing the book’s graphic torture sequences, instead putting a heavier focus on the ambiguity of Bateman’s actions on their own. The film juxtaposes humorous monologues about some of the 80’s most materialistic tunes to Bateman’s murders, in order to pursue the film’s bizarrely-delivered critique of the possession-driven society we live in.

Through its dark humor, graphic imagery, and off-kilter tone, its message is pitch perfect.

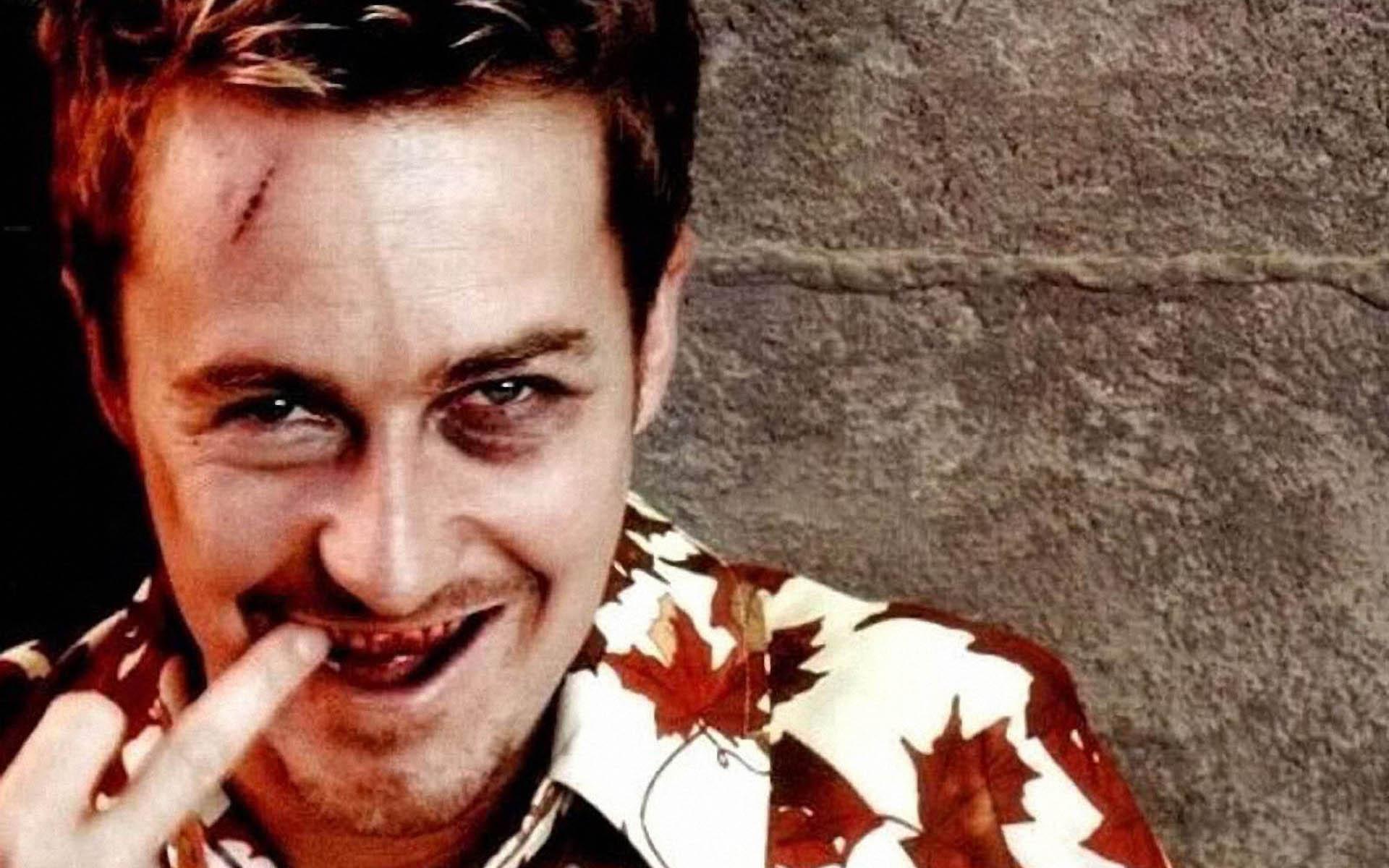

3. Fight Club (1999)

Everyone knows about it – regardless of whether they’re allowed to – and it will go down in history as one of the most iconic films of all time. Unfortunately, this leaves little light for the original novel by Chuck Palahniuk, which is of equal brilliance.

Enlisting the likes of Hollywood heavyweights Brad Pitt, Edward Norton, and Helena Bonham Carter, director David Fincher swings this violent film through an increasingly chaotic yet never dull series of events, initiating with two men meeting on a plane, fighting outside a bar, and concluding with the destruction of some of the biggest banks in the world.

The film has been absorbed into popular culture without much thought as to what it actually means. Its shocking and iconic plot twist, combined with Pitt’s impressive abdominal muscles, left many needing little else to take from it, but anyone who doesn’t look a little deeper in it is quite gravely missing out.

Note the opening copyright warning; it’s actually a message from Tyler Durden about corporate consumption and the film’s overarching message hammered so heavily into the film’s narrative it’s a wonder people miss it: “The things you own end up owning you.”

The film’s quirky and dark humor intermingled with its violent undertones in a successfully shocking way to make it wholly unique and ahead of its time, but it has to come from somewhere.

Palahniuk’s novel follows very similar occurrences, although giving more surreal sequences and less interplay between Marla and The Narrator, and explores its overarching critique of consumption culture in a slightly different manner. Although, of course, it does differ from the film, it does so in only the slightest of ways, making it both a great adaptation and a great film.

2. Adaptation (2002)

How do you sell a film adaptation of “The Orchid Thief” to someone who has no interest in such a strange topic? All it took for me was its adaptor – the great and unique Charlie Kaufman – but the fact it holds a 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes might help too.

One of two semi-biographical adaptations (the other one being “Confessions of a Dangerous Mind”) by Kaufman, it takes a very different and incredibly brave approach to the act of adaptation. Kaufman puts himself and his non-existent twin brother inside his screenplay as twin writers struggling to adapt “The Orchid Thief”.

Obviously, there’s an incredibly unique thing that makes Kaufman tick, with his twin working as bizarre as anything, but this film not only boasts the genius of his writing, but the deft direction from Spike Jonze and Nicolas Cage at his best.

I don’t need to go into the differences between Susan Orlean’s book and the film; the very plot line reveals that and Kaufman very much honors the complexities of his inspiration, just with his own insights into the human mind that are so prevalent in his work.

1. Naked Lunch (1991)

To understand “Naked Lunch”, one must understand it is not to be understood. There is a line of narrative that William S. Burroughs created in the spiraling madness that was his own drug addiction, and it informs everything he writes. His characters seem to inhabit a world where pain seems to wait at every corner, and where no real sense is found in this pain; it does not make any sense outside of the context it inhabits.

David Cronenberg, the master of body horror and one of the auteurs of directorial vision, uses both Burroughs himself and his novel “Naked Lunch”, drawing them together for the only possible adaptation to be made of that strange and tormented book.

Burroughs once called his work “an exorcism” and I shall elaborate on perhaps the greatest mystery of his life. Fleeing from the law to Mexico with his wife, Burroughs (a homosexual man who’s still in the closet) began drinking heavily with his wife in taverns and bars.

One day, he declared he would perform a “William Tell” (who shot an apple off of his son’s head with a bow and arrow) and took a revolver out, placing a shot of alcohol on his wife’s head, and aimed the gun and fired. The bullet hit and killed his wife, and he fled back to the United States to spiral into an uncontrolled addiction, whereupon he wrote his infamous novels “Junkie” and “Naked Lunch”.

Cronenberg’s film adaptation takes the lead of “Naked Lunch” and merges him with Burroughs himself; the connection established is confusing to viewers who are unaware of the author himself.

Played bravely by Peter Weller, the lead character acts as an ex-addict bug exterminator, but both he and his wife (Judy Davis) are addicted to the bug spray and thus ensues a series of psychedelic, mind-warping and baffling displays that are both humorous, decadent and twisted.

Burroughs once said his novel “could be read in any order”, meaning it’s be almost impossible to be adapted, so give credit where credit is due. Cronenberg permeates an atmosphere of a queasy gloom that hypnotically pulls us through its messy narrative line.

“Naked Lunch” is often lost in this director’s body of work and hidden in the history of literature, but it shouldn’t be. It stands as a landmark testament to the depravity found within the human mind, and a harrowing revelation about the nature of the human condition. One simply needs a strong stomach and a constant reminder: this doesn’t make sense and it probably never will.