Black and white films hold an important place in film history: before three-color Technicolor was introduced in 1932, all films were shot in black-and-white. Even after the advent of color film, many filmmakers chose to shoot in monochrome as both an aesthetic choice and because the film stock was cheaper, which afforded filmmakers to experiment with the medium.

However, one of the drawbacks of black-and-white film is that it often looks dated to modern film fans, and there’s a certain contingent of viewers who absolutely refuse to watch them.

While black-and-white films are often shorthand for “old movie” in a lot of film fan’s minds, there are also many that–due to the technical brilliance of the cinematographer, art designer, and director–look crisp and clean like they were shot yesterday, and whose subject matter, style, and themes were either ahead of their time or are altogether timeless.

Perhaps not coincidentally, many of these films are from masters of the craft: Godard, Kubrick, Welles, and Kazan all make appearances on this list, proving that even when constricted by the technical limitations of their time, a filmmaker could produce a work that even over half a century (or more) later look as modern as the latest arthouse release.

1. Alphaville

Jean-Luc Godard was associated with France’s “New Wave” filmmaking movement, whose practitioners often eschewed traditional film setups, promoted discontinuity in editing, and experimented with the narrative form. Many films produced from this loosely affiliated group have since become classics that are studied in college classrooms and have inspired generations of aspiring filmmakers.

As a director, Godard has produced some enduring classics of his own, including Breathless, a touchstone in French cinema. And as timeless as that film is, there’s another movie in his body of work that was even more forward-looking, and set in the future.

Alphaville is a dystopian sci-fi film that also heavily leans on film noir in its aesthetic. While there are no futuristic sets, part of its effectiveness is in how Godard selected locations that would still give the illusion that the story was taking place in the future.

Looking back at this strategy in 2017, it’s startling how precient Godard was in 1965, since much of the world looks similar to how it did back then. Since (mostly) only our personal technologies have radically developed since the mid-60’s, many cityscapes still looks remarkably similar to how they did over half a century ago.

The sci-fi elements in the film are also surprisingly modern: our protagonist, a secret agent named Lemmy Caution, carries an Instamatic camera around with him, which he uses to take pictures of clues, much like one would a cell phone; the ruler of Alphaville is a decentralized computer system known as Alpha 60, which is omnipresent throughout the city, much like the internet would one day work similarly; and behaviors are strictly monitored and regulated, with concepts like “love” and “emotion” having been eliminated as a dystopian nod to the novel 1984.

Caution’s mission–to find the professor that built Alpha 60 and destroy the totalitarian machine that runs Alphaville–becomes intertwined with falling in love with a citizen of Alphaville who has no understanding of the forbidden concept of love. As an arthouse sci-fi flick, this film still holds a lot of appeal for both fans of the genre and of classic movie fans usually put off by black and white films.

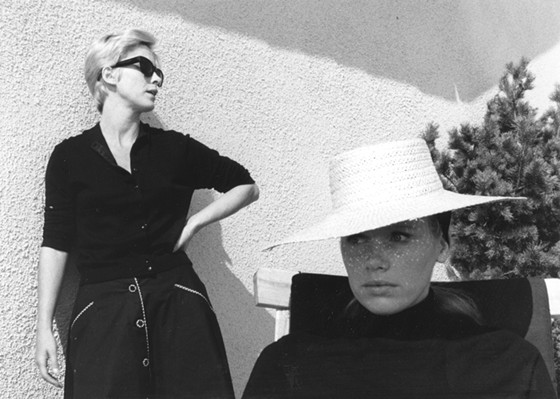

2. Persona

Ingmar Bergman’s work was always a challenging prospect, and getting into his oeuvre takes some time no matter how savvy you are in film. While heavily influential in the history of movie-making, his work is better known as a reference to many filmgoers than actually watching his films. This is understandable for a body of work that was solely produced in Sweden, with its dialogue in Swedish, and whose default mood for its characters and plot was angst and existential despair.

While The Seventh Seal is a major work, it’s best-known to modern Western audiences through the parodies it inspired rather than the film itself; even the widely celebrated Scenes from a Marriage is over four hours long and is a heavily dramatic work to digest.

However, there is at least one film of his that is not only approachable to modern audiences, but since its release in 1966 has gained considerable esteem among its unexpected tertiary audiences: Persona. The story is simple enough: an actress suffers from a nervous breakdown and is hospitalized, falling mute in the process. There, she is taken under the care of a young nurse, who takes her to a seaside cottage to recover. The two women engage in a battle of wills, as the nurse seems to lose her identity–and sanity–as time goes on.

However, what gives Persona its impact is in its shocking and confrontational style: as an intense psychological study of two unstable women, the film’s editing and pacing reflects the shaky, fraught emotions the characters are experiencing. A kaleidoscopic montage that begins the film sets its location as somewhere other than objective reality. The blocking in some shots overlap the two characters’ faces, and in one shot, both faces are interposed, suggesting that the two characters we’ve been watching are actually dual sides of the same woman.

It’s a complex and mysterious film that plays more like a psychological horror film than a drama. While appreciated in its time, its influence has only grown since: both Robert Altman and David Lynch would make films inspired by Persona, and the body of criticism surrounding this film continues to grow to this day. A radical film even to modern audiences, Persona is still perhaps far ahead of its time.

3. The Night of the Hunter

With the iconic LOVE and HATE tattoos across his knuckles, Robert Mitchum’s reverend-turned-serial killer Harry Powell is well-known in popular culture, even if it’s just for the similar, abbreviated version of these tattoos that Sideshow Bob is shown to have on The Simpsons. But actor (and one-time director) Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter has had a lasting power in cinema history long after its initial release.

Adopting the style of German expressionists, Laughton created a unique-looking suspense story that follows the diabolical Powell as he closes in on two children whose father had stolen and stashed a large sum of stolen money, only confiding in his children where he hid it before being killed (in jail, by Powell, to whom he had just told this information).

Reverend Powell gives chase, marrying and then murdering their mother to get close to the money, and the children keep one step ahead of him…for a while. The child actors’ performances, and (especially) Mitchum’s powerful and unnerving turn as the loathsome and unrelenting Reverend Powell, are sophisticated and nuanced; meanwhile, the dark plot and ineffective adults that populate this vaguely noir-ish story contribute to the film’s menacing tone.

Unsuccessful upon its release in 1955, leading Laughton to abandon a promising directorial career, the film’s influence has risen over time, with later audiences recognizing the striking cinematography, murderous and amoral antagonist, haunting score, and singular story as prescient elements for an American film produced in the 1950’s to have.

Since its release, it has been included in numerous “Best of…” film lists, and Roger Ebert had declared that “It is one of the most frightening of movies, with one of the most unforgettable of villains, and on both of those scores it holds up … well after four decades.” Now six decades after its release, it’s still a captivating and truly suspenseful film to watch, and one that an unsuspecting modern viewer will be surprised to find how long ago it was made.

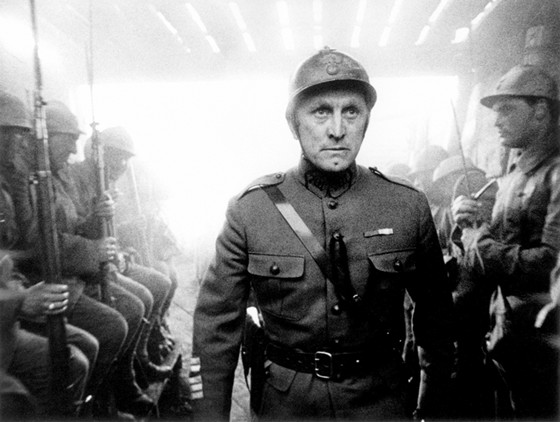

4. Paths of Glory

World War I–an event that now occurred a century ago–inspired a wave of anti-war books and films after its conclusion. The brutal trench warfare and use of chemical weapons in that war forever changed the rules of engagement for future wars to come and changed the minds of many about the nature and purpose of war.

Although All Quiet On the Western Front is perhaps the most well-known anti-war film set during this global conflict, Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory–released in 1957–is perhaps the most harrowing and intimate depiction of the desperation that the trench warfare of WWI inspired in its participants.

Based on a true story, it follows the court-martial of three soldiers (who are chosen to represent a hundred soldiers who refused to attack in what would essentially be a suicide mission), and a colonel (played by Kirk Douglas) who attempts to save them from execution. Featuring Kubrick’s crystal-clear deep focus and unique cinematography, Paths of Glory is an affecting anti-war film that looks at the dehumanization that occurs within the military towards its own soldiers during wartime.

Due to this, it was a controversial film among the West’s military at the time of its release; it was not released in several countries–including Switzerland, France, and Spain–for decades and was banned from being shown on American bases. As with most Kubrick films, the technical aspects of the film–cinematography, lighting, blocking–are impeccable, and the tension of extreme warfare is palpable in the actors’ performances.

Depicting the savage brutality of a war fought a century ago in a film made 60 years ago, Paths of Glory is a period piece that looks as sharp and whose subject matter is as relevant as it was the day the print was first struck.

5. Touch of Evil

Orson Welles has been (rightly) hailed as one of the greatest filmmakers all time. Although it seems unnecessary to mention, his debut film Citizen Kane is still recognized as one of the most innovative and influential films ever made.

However, a great film doesn’t make it timeless; although it is a fantastic film, much of Citizen Kane comes across as dated as the newsreels that it satirized; even its influence doesn’t shield it from criticisms that much of its innovation is lost on modern audiences, particularly since said innovations been adapted, parodied, and recycled ad infinitum in the intervening years.

Although Welles directed a number of notable films after his debut, many of them were low-budget affairs that shined despite their limitations. However, in 1958–a full 17 years after Citizen Kane’s release–Welles was afforded both the budget and artistic freedom to innovate once again. The result is an enduring masterpiece that is still impressive to the jaded and more experienced audiences of today.

Touch of Evil is to noir film what Citizen Kane was to filmmaking in general: an innovative entry into a (by then) established stylistic niche that somehow went further and accomplished more than all of the films in its genre had previously accomplished.

Like many great films, the plot is simple: a DEA agent (Charlton Heston) in Mexico and his American wife (Janet Leigh) cross the border, only to find themselves embroiled in intrigue when a time bomb–having originated from Mexico–goes off just inside of the US border. A corrupt local police captain (played by Orson Welles at his heaviest) interferes with the investigation, and escalating tensions lead to a dramatic conclusion.

The plot thickens, as usual, and the drama ratchets up as only it can in the hands of a master like Welles, who could have arguably become America’s Hitchcock, as this film demonstrates. Some scenes are well-known, such as the uninterrupted 12-minute long-shot that opens the film as we follow the ticking bomb from Mexico into America, while others depict the rising tension through masterful dramatic staging, such as a scene where Leigh’s character is being menaced by a gang in a bar, or else in low-angle shots that reflect similar setups in Citizen Kane, only the character being put on this virtual pedestal is an obese and corrupt police captain.

What makes the film modern is its earnest approach to the subject: although Welles is remembered as a well-regarded director today, Touch of Evil was a last-ditch attempt to secure mainstream success in Hollywood for him.

As such, Welles threw himself into the production, closely orchestrating the filming and selecting the right crew (including legendary cinematographer Russell Metty, who worked on over a hundred films, including his Academy-award winning work on Spartacus) to make this memorable entry into the film noir genre, creating one of his most lasting contributions to film history–and possibly his most accessible film to modern audiences. With its innovative long shots, an almost meta take on the film noir genre, and a crisp, detailed aesthetic, to contemporary filmgoers Touch of Evil comes across less as an old movie than a modern classic.