We hear the phrase often: the director’s vision of his movie was changed because of “studio interference.”

In the day and age where big-budget movies are often more of a brand than a film, executives are known to meddle in the creative side. No amount of success and experience can save a director and his team from being disrupted.

In truth, many films have been improved when the studio butted in. The Godfather, The Wizard of Oz, and Lord of the Rings are just a few examples where the distributors played a key role in developing the proper version. But more times than not, the increased involvement of these executives creates a too-many-hands-in-the-kitchen approach that leaves the original work unrecognizable.

In the case of these films, a few were eventually done justice by director’s cuts. But for others, we’ll never know how well-done the original vision was due to such severe differences.

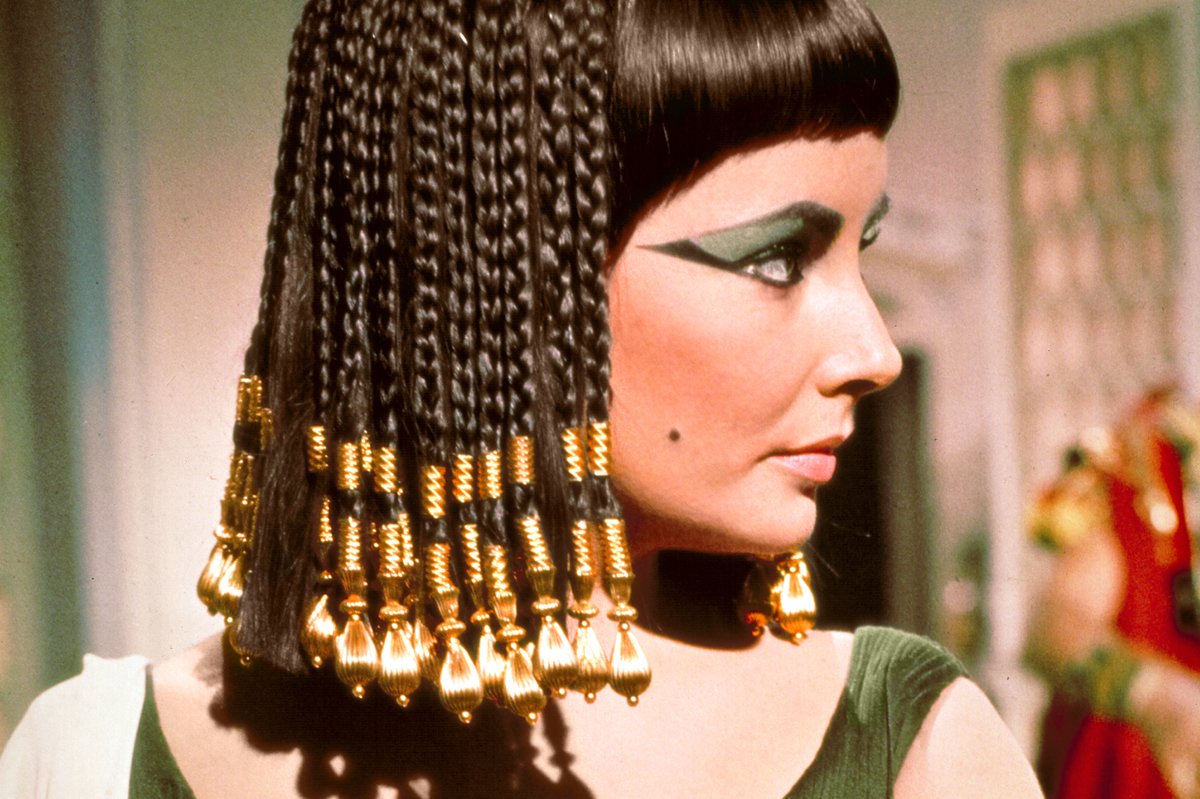

1. Cleopatra

It was at the time the most expensive movie in history. Expectations were through the roof for 20th Century Fox. There were elaborate sets unlike anything ever seen, an epic tale with an even more epic runtime, and megastars Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. Naturally, with such a big budget, there were studio fingerprints all over it.

Forget the fact that the affair between Burton and Taylor caused much of the drama on-set, because the movie itself had all sorts of issues behind the scenes. Originally scheduled to be two installments, Cleopatra instead ended up as a three-hour mess of a movie after Fox made all sorts of firings in the production department.

Editing out hours of content and changing producers at will created a lopsided and still overlong film that nearly bankrupted them. And this was despite All About Eve and A Letter to Three Wives director Joseph L. Mankiewicz being at the helm. He was long-established and had done justice to Julius Caesar a decade before.

He was handed the reins only after RoubenMamoulian had been taken off the project, one of many times Fox took matters into their own hands. What came of it was a production that, if adjusted for inflation, would be north of $340M today.

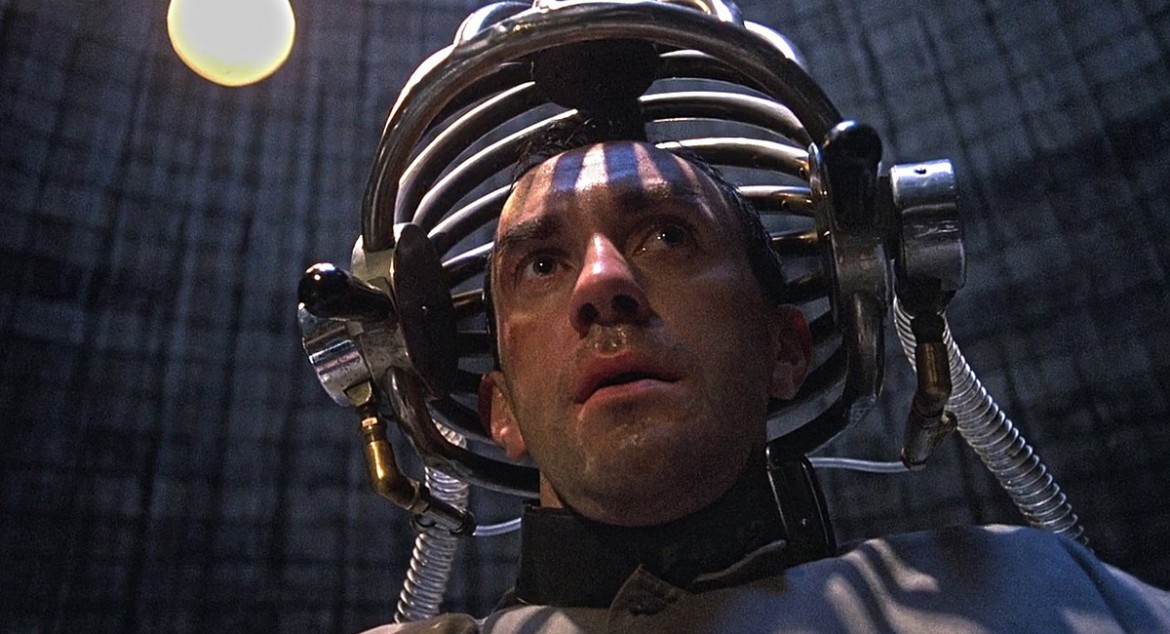

2. RoboCop (2014)

What’s the best way to remake an 80’s sci-fi cult classic, one with extravagant violence, biting satire, and one of the better directors of his time? Not sure, but it doesn’t involve making a diluted and meaningless mainstream movie with none of the original’s gut.

And that’s exactly what Sony and MGM did.

Instead of branching out to a fresh, but still wickedly satirical version director Jose Padilha had in mind, the distributors rejected most of his ideas. Even after the failures of two sequels in the early 90’s, they thought a more cookie-cutter approach would actually work. It got to the point where Padilha described working on the project as “hell” because he had to fight so hard to keep any of his vision in the movie.

Three different writers were credited to the project, two of which were Edward Neumeier and Michael Miner, who scripted the original movie. Even with them on-board, this film went through several rewrites and the departure of Hugh Laurie, the would-be villain.

In the end, we got what many expected: a sleeker and more up-to-date movie with no originality or bite to it. Even with talent like Gary Oldman, Michael Keaton, and Jackie Earle Haley, this film felt dead inside.

Taking even more from the style of the original was the fact they toned everything down. MGM wanted the PG-13 rating to maximize profit in a time where they were struggling to stay afloat. Sony wasn’t doing too hot for itself either at the time, critically or financially, and has still yet to come out of its funk.

3. Brazil

This is one of the few cases in which the final project didn’t hurt the legacy of the film. But while Brazil is considered one of the most influential sci-fi movies, the original version ended in a way that seemed to contradict the rest of the movie.

20th Century Fox distributed director Terry Gilliam’s 142-minute cut internationally, but Universal and producer Sid Sheinberg were unfortunately in control of domestic rights. They sliced the film to a 90-minute watered-down version that they thought would appeal better to American audiences.

For a movie that attacks consumerism, it seemed as if Universalwas aiming for the opposite. With poor test screenings bringing changes, this new hour-and-a-half take was created with a happy “Hollywood” ending and other edits to try and appeal to a broader audience.

This is now known as the “Love Conquers All” version, a sarcastic response by Gilliam to the studio’s take. After a long fight with Universal and a long-delayed release, the director illegally showed his director’s cut to critics and film schools. He also took a full-page ad out in Variety to voice his disgust and demand the studio to release his version of the movie. They eventually would after the 142-minute original won the Best Picture award from the Los Angeles Film Critics Association.

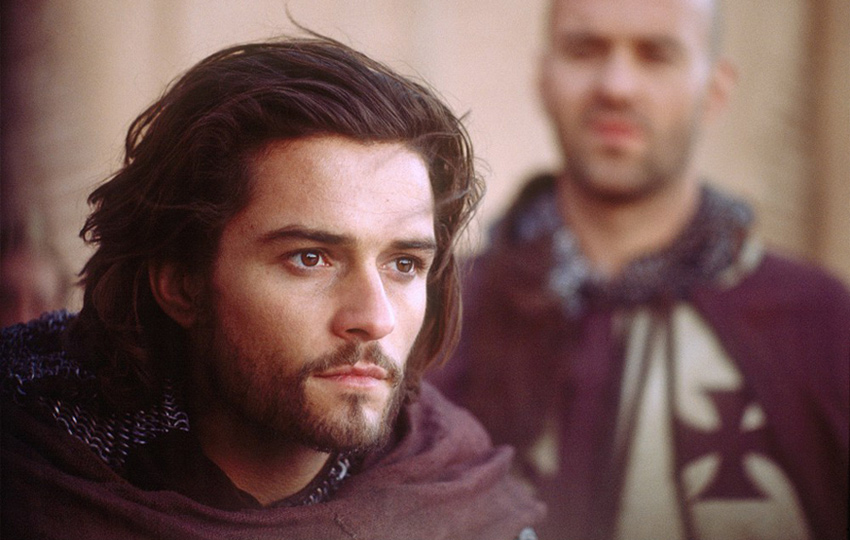

4. Kingdom of Heaven

We hear it often nowadays when studios interfere, that the director’s cut will be much improved. That’s not always the case. We’re looking at you Zack Snyder.

But as for Kingdom of Heaven, it may give Brazil a running for the greatest improvement from one version to another. Chopping Scott’s three-hour-plus movie by 45 minutes was a senseless decision. The movie was still left well over two hours, but cut out some pivotal content.

It didn’t take apart a theme like in Brazil, or erase context like in many other movies. Instead, it cut out an important character in King Baldwin Ventirely, and fumbled around a few plot points. Many of those storylines weren’t properly summed up by the theatrical version, and the development of several characters likewise suffered.

This wasn’t the first time Ridley Scott had been undercut by 20th Century Fox. Blade Runner had also seen massive changes, which led Scott to release a director’s cut afterward and eventually a polished “final cut” 25 years after its 1982 release.

Scott has continued to work with Fox, but was obviously upset at how Kingdom of Heaven was handled. He concluded that the studio had tried too hard to play to the wishes of preview audiences, which led to the significant shortage.

5. The Golden Compass

Amid the swell of big-budget YA franchises, The Golden Compass seemed like a no-brainer for New Line Cinema. They’d struck gold with Lord of the Rings, and they were confident enough to throw a $180M budget into Compass. That was $30M more than Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix from the same (2007) year.

But it never even got close to the success of Chronicles of Narnia, much less the wizarding world. A lot of it had to do with the studio deciding to reorder many of the book’s scenes, coupled by drying up the darker moments and themes from His Dark Materials. New Line ended up releasing the movie about 40 minutes shorter than originally planned by director (and Rogue One collaborator) Chris Weitz. It was about an hour shorter than it should’ve been to cover all the book’s crucial points.

Many people involved with the film tried to blame the backlash of the Catholic church for its failure, but Potter had the same recoil from many Christian organizations, and they made billions.

In truth, the potential trilogy was killed off by a slew of problems: the gloomier ending was taken out, the content poorly twisted, the runtime reduced, and the themes toned down. And New Line, just as they deserve credit for the achievements of Lord of the Rings, deserve blame for the critical and box office failures of Compass.