Sometimes the story behind the scenes is nearly as compelling as what made it onto the screen. Here are 10 unusual production histories you maybe weren’t familiar with:

1. Roman Polanski’s Macbeth (1971)

Once upon a time, Roman Polanski was preparing to direct a science-fiction adventure film titled Day of the Dolphin… then the Manson family came along. After the brutal murders of his pregnant wife and several close friends on the evening of August 9, 1969, Polanski entered a deep depression and forgot all about Dolphin (it ended up going to Mike Nichols).

The project he chose instead was an adaptation of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth, but Polanski didn’t want to make a stuffy costume drama – his Macbeth would be unflinching, disturbing, grimly atmospheric. He planned to embrace the horrific aspects of Shakespeare’s tale, and to emphasize them.

Multiple studios – Paramount, 20th Century Fox – were leery of the property and passed, resulting in Playboy magnate Hugh Hefner stepping in to offer financing.

The result is a bold and sadistically violent picture with some of the most naturalistic Shakespearean acting ever captured on film, but the production was plagued with problems, literally from the start: a cameraman nearly died on day one when a gust of wind blew him off a tall scaffold.

Polanski’s Macbeth was released to little fanfare and a meager box office return but has attained proper recognition over time, and Polanski recovered smoothly. After all, Chinatown was just around the corner.

2. Electra Glide in Blue (1973)

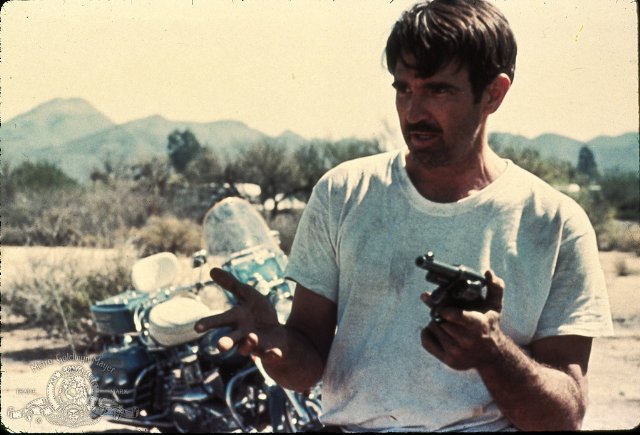

Sort of an anti-Easy Rider, Electra Glide in Blue tells the story of motorcycle cop John Wintergreen (Robert Blake, in a career-best performance) whose life is irrevocably altered by a murder case in his rural Arizona town.

It was the first and only film to be directed by James William Guercio, producer of the band Chicago. He hired famed cinematographer Conrad Hall (In Cold Blood, Cool Hand Luke), but the two clashed badly; they agreed that Hall would shoot only the interior scenes, leaving Guercio to film the exteriors as he desired.

Robert Blake, a notoriously demanding actor never known for his modesty, was later quoted as saying: “I directed Electra Glide. Didn’t put my name anyplace on it. Put another guys name on it. He was never near show business, film, before or since.”(1).

Despite this volatile mix of egos and perspectives, Electra Glide in Blue turned out remarkably well. One of the best films of the 1970’s, it’s an overlooked classic that deserves a wider audience.

3. Caligula (1979)

Penthouse founder Bob Guccione had a vision. Bob wanted to make a different kind of adult film, one that combined explicit pornography with a strong narrative and Hollywood production values. He seized upon the story of Roman emperor Caligula, feeling it provided the perfect mix of sex, violence, and drama, and sought out intellectual author Gore Vidal to write a screenplay for the fee of $200,000.

Bob was disappointed with Vidal’s script, felt it was overly talky and that it placed too strong an emphasis on homosexual content. Guccione and the Italian director he’d hired, Tinto Brass (he first offered the job to John Ford), proceeded to heavily re-write the script, increasing the sleaze quotient and shutting out Vidal in the process.

The cast they assembled is impressive, including such respected figures as Malcolm McDowell, Peter O’Toole, Helen Mirren, and John Gielgud, all of them taking part in activities that one would never, ever expect them to. A monumentally gory historical epic sprinkled with liberal doses of hardcore porn, Caligula plays like a catalogue of depravity.

Many participants were only partially aware how graphic the film was – after filming had wrapped, Guccione shot additional raunchy material on his own and inserted it into the picture, greatly upsetting much of the cast and crew. Gore Vidal had his name removed, and most of the actors seem to regard it as a black mark on their resumes. It does have its fans, though: it was Hunter S. Thompson’s all-time favorite film.

4. Neighbors (1981)

In the early 80’s, John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd were riding a tidal wave of success. First came Saturday Night Live, then the Blues Brothers film; as the John and Dan star rapidly rose, film studios were tripping over themselves to ready the comedic duo’s next project. That project turned out to be Neighbors, an adaptation of a darkly comic novel by Thomas Berger.

The book revolves around mild-mannered suburbanite Earl Keese and the arrival of a strange young couple next door who, in the course of a single evening, turn Keese’s world upside down.

John Avildsen (Rocky, Joe) was hired to direct, based more on his exceptional body of work than his personal reputation – he’d been fired from Saturday Night Fever after clashing with John Travolta over the ending.

Aykroyd was cast as Earl and Belushi as the rambunctious neighbor, Vic, but at the last minute the two decided to switch roles, wanting to defy expectations and play against type.Avildsen thought the idea ingenious, but this was probably the last time the three of them would ever find themselves in agreement.

Belushi’s substance abuse was at its worst during filming, resulting in intense star fits, forgotten lines, and numerous accidents (he almost died after insisting on performing a drowning stunt with sandbags tied around his feet); feeling the material was being mishandled, he aggressively tried to get John Avildsen fired, constantly repeating that the director didn’t understand comedy.

Belushi wanted punk band Fear to provide music for the film and he recorded several songs with them, but Avildsen and the producers found the music unlistenable and rejected it, further infuriating their star.

Every decision from Avildsen was loudly questioned by Belushi, while Aykroyd vainly tried to keep the peace and help salvage the film career of his best friend.

It all culminated in a screening for the cast and crew where Belushi, so upset at the film unfolding before his eyes, took off his shoe and slammed it on his armrest every time something occurred that he objected to. According to those present, he was beating the hell out of that armrest.

5. Death Wish II (1982)

1982. Michael Winner was approached by Menahem Golan and Yolan Globus, heads of the Cannon Film Group, with the prospect of making a sequel to his 1974 film Death Wish.

Winner balked, feeling the original film was, in his words, a “one-joke picture”(2). He was also unnerved by the state of the Cannon offices upon his first visit: “The place was filthy and they were besieged by creditors, people walking in left and right screaming about not being paid.”(2). Star Charles Bronson refused to make the film without him, though, so a flattered Winner reluctantly agreed. Death Wish II was shot mostly in Downtown Los Angeles, with real pimps, druggies, and homeless people used as extras.

Charles Bronson’s brother was an alcoholic living on Skid Row at the time, and he would regularly visit the set for financial help, but never asked for more than $20: “If you give me more than twenty, they’ll kill me for it”(2). Michael Winner happened to have Led Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page for a neighbor, and got Page to score the film for the fee of $175,000 (Golan and Globus wanted Isaac Hayes).

According to Page, this period was “possibly the darkest”(2) in his life, his band having recently dissolved and his heroin addiction steadily gaining strength.

The film premiered at Cannes to scathing reviews – while the original was widely regarded as a slick and efficient thriller, Death Wish II was accused of being a sleazy, misogynistic disgrace with a misguided message and gratuitous rape scenes. Fans of eccentric cinema can find much to love in Death Wish II, but your average filmgoer is likely to want a shower afterwards.