6. Diva (1981)

Critics can sometimes be a bit… well, vengeful, if they don’t feel as if they have “discovered” a filmmaker, either an on-fire newcomer, or a longtime worthy who hadn’t gotten their just due until championed. Jean-Jacques Beineix, unfortunately for him, didn’t quite fit into either camp. He was nearing 40 when he finally made his directorial debut, after being one of France’s most professional assistant directors, working for the likes of Claude Berri, Rene Clement, and even that one time (much joked about) French-loved-American icon Jerry Lewis (and he surely deserved a medal for that alone). It took Beineix awhile but he chose the property for his first vehicle well.

Well known in France at the time (and later exposed elsewhere, mostly thanks to this film) was a very trendy, pop culture-oriented series of mystery/suspense novels (though the mysteries were never a big focus) by a writer known only as Delacorta. Those adventures featured the unlikely pair of Gorodish, an artist of living and a real cool cat; and Alba, the way underage luscious blonde, a runaway with a surprisingly mature feel for cool culture with whom he has a most interesting (though apparently chaste, odd to say) relationship.

Though the filmmaker certainly kept the characters (albeit casting Alba with the decidedly not blonde Vietnamese actress Thuy An Liu), he shifted the focus of the novel he chose, “Diva” (and all novels in the series had titles consisting of one four letter word), from the pair a bit.

The main character here is Jules (Frederic Andrei),a jazzy, cute young messenger (riding around on his moped) who has a monumental crush on operatic diva Cynthia Hawkins (actual American opera singer Wilhelmina Wiggins Fernandez, not well known before this film). Cynthia has a most peculiar quirk, though. She wishes only to experience the live stage and won’t allow her voice to be recorded (a rather dubious demand in modern times).

So, Jules sneaks recording equipment into the concert hall in his messenger bag and captures her voice (and steals her gown after getting backstage). However, two Asian men, ruthless record pirates, observe him and are determined to steal the tape. It doesn’t help that another tape, involving a drug ring and corrupt police officers, happens to coincidentally get mixed in with the diva tape and, thus, two sets of dangerous people are on Jules’ trail!

Yes, the plot is convoluted but it’s hardly the main point. Rather, it’s is a big peg for a wonderful amalgam of exotically mixed people, flamboyant villains, a suave hero-helper in Gorodish (Richard Bohringer), hyperkinetic action scenes (especially a subway-motorcycle chase), and, above all, a variety of dazzling images.

The French critics didn’t support the film for reasons stated (and have rarely had a good word for the filmmaker since, despite other notable films) and France certainly didn’t chose the film to be its official Oscar entry, but the US critics and discriminating film goers took it to heart and it has a place of affection in the US to this day.

7. Mona Lisa (1986)

One of the great cinematic losses of 2014 was that of British character actor turned unlikely star Bob Hoskins. Hoskins was short, decidedly unhandsome, cockney, rough hewn, a wonderful actor and always somehow likeable, even when the character being played wasn’t always supposed to be. He had been connected to the public ever since his big breakthrough in author Dennis Potter’s now-classic TV mini-series “Pennies From Heaven” (1978).

Most likely the height of his somewhat erratic stardom was the hugely popular fantasy mystery-adventure “Who Framed Roger Rabbit?” (1988) but his apex as an actor is generally thought to be his multi-award winning performance in “Mona Lisa” (no Oscar, though, as the Academy just had to choose that year to make it up to Paul Newman for decades of neglect by honoring his weakest nominated performance).

This touching film from noted Irish filmmaker Neil Jordan focuses on the character of George (Hoskins), a rather low-level mobster who’s getting out of jail after several years. He’s come back to a world where he’s the low man on the totem pole and the local crime boss (Michael Caine, shining in what’s more a large cameo than anything else) assigns him to be the chauffeur to a high-priced call girl and woman of color named Simone (Cathy Tyson, who seemed to make a career of playing prostitutes).

The naturally warm George takes to Simone and she, in turn, asks to help her with an urgent request, namely to help her find a fellow prostitute with whom she has lost contact and fears is in trouble. George, an oddly naïve man in some respects, agrees and soon both are in over their heads.

Jordan was always a filmmaker to explore themes of love, loss, renewal and ultimate hope and “Mona Lisa” is certainly no exception. However, if any Jordan film ever hinged on one element, it’s this one and Hoskins’ performance.

The story becomes rather obvious as it goes along but the viewer always cares about George thanks to Hoskins. At the end, when George finds some happiness, albeit by settling for less, it feels satisfying, even if not completely plausible. This picture, finally, is what it always was – a monument to a fine actor.

8. A Brighter Summer Day (1991)

Sometimes life just doesn’t play fair. In the 1980s and 90s, an interest began to be taken in films from areas of the world which had previously been somewhat overlooked, if not ignored. A major territory in this regard was the island nation of Taiwan, the place where many from mainland China had immigrated starting in the late 1940s. During this fertile time, screenwriter and director Edward Yang began to come into his own.

Yang was a master with actors, but a part of this was the fact that he gave those actors something to work with in his films. He wrote long, multi-layered scripts with three dimensional characters and larger, overarching themes. He also had a relatively simple but lovely visual style. A Yang film was something special and, sadly, there were only seven of them (in addition to a number of stage and TV productions) before Yang’s death from cancer in 2007.

In many parts of the world, his best known film is the excellent family comedy-drama “Yi Yi” from 2000 (also his last film). Outside of Asia, his films until recently have been rather hard to see. With greater visibility in the current era, a number of his other films are gathering audiences. Many have acclaimed his early film “The Taipei Story” (1985) but, increasingly, many are coming to consider the epic “A Brighter Summer Day” his masterpiece.

This film examines the youth culture of Taiwan circa 1961 (the date of the real life crime which inspired the film). This was the first generation to have been brought up in Taiwan with no memories of mainland China as “homeland”. The film also examines how Western culture (represented by Elvis Presley and rock ‘n roll in general) started changing the minds and attitudes of the youth of that country.

The storyline of this nearly four hour (!) film concerns the wayward path of a disaffected youth (Chen Chang, at the start of a starring career) and involves rival gangs and young love, all leading to a shattering conclusion. This may seem the stuff of trite melodrama but it hardly plays that way. Yang was interested in human beings and how they tick and what larger forces made them that way and how they relate to one another. Give this film enough time and its place on this list may be questioned, because it is now in first place on many other lists.

9. The Long Day Closes (1992)

The film world may be thankful that the British government, at least for a long time, helped subsidize worthy young cinematic talents through government-supported TV channels, and later, independent cinema. Several interesting young filmmakers were given a chance (now sadly closed off, for the most part) and one young man with a vision, even if no one else had been worthy, made it all worthwhile.

That young man was Terence Davies, often considered Britain’s finest living filmmaker by the relative few who have seen his films. Though he has cautiously moved into the world of commercial cinema (though his recent “A Quiet Life” in 2016, concerning reclusive poet Emily Dickinson, is hardly the stuff of blockbusters).

For many, the essence of Davies as a filmmaker are the three films which started his career professionally – “Trilogy” in 1983, “Distant Voices, Still Lives” in 1988, and “The Long Day Closes” in 1992. All three draw heavily on Davies’ personal experiences growing up in drab Liverpool in the time just after World War II (yes, the same place and time that produced The Beatles, except Davies didn’t sing).

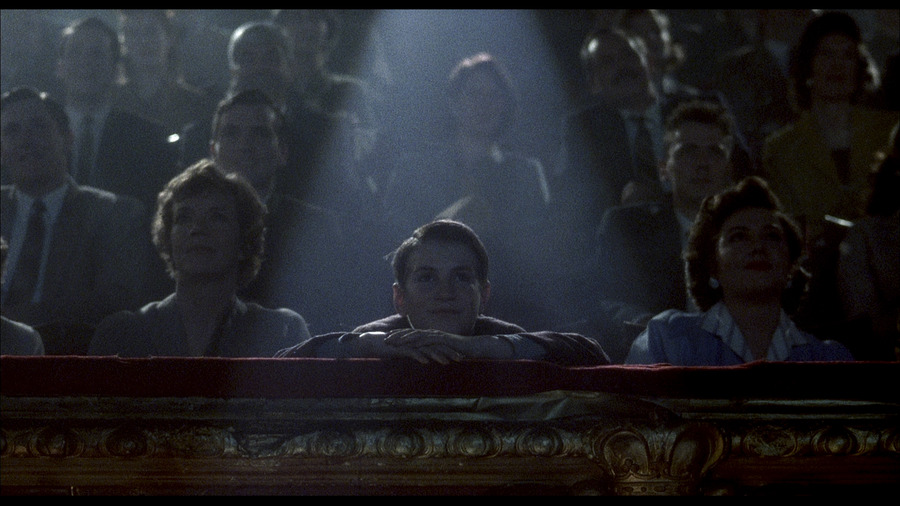

The three films trace the growing-up years of a boy who is bullied for seeming so strange to others, even some in his family, who has a turbulent home life (though blessed by a loving mother), and who is able to find some solace from the cruelty and dreariness of it all at the local movie palace.

There is nothing very original in all of this except that 1.) It’s extremely personal to the filmmaker, and 2.) Rather than imposing phony dramatics on it all, as so many coming-of-age films do, the films are told without the conventional rising and falling dramatic action of a usual dramatic production.

Using a most discerning and artistic eye, married to an uncanny knack for choosing existing musical pieces as counter-punctual grace notes (in the case of “The Long Day Closes”, Bach is brilliantly employed), Davies’ early films are more like cinematic or dramatic collages than feature films.

“The Long Day Closes” leaves much of the unhappiness of the earlier films behind to concentrate on the joys of going with “mum” to the movies at a most interesting time in the medium’s existence. The son and mother are played by Leigh McCormack and Marjorie Yates, two most subtle actors who conveyed just what the film needs.

Perhaps this sort of film could only have been created for a short time in either a filmmaker’s life or an industry’s existence. Happily, that time came along at the right moment for Terence Davies.

10. Taste of Cherry (1997)

For many understandable reasons, several third world countries, sub-continents, and continents didn’t make getting into the creation of cinema a high priority (seeing to the basic needs of life in a harsh environment can do that). However, these now emerging filmmakers are bringing forth some of the most interesting cinematic works in the world today (and it’s odd how troubled times and places can produce the best in film).

The Middle East has proven to be second to none and Iranian cinema has proven to be surprisingly vital given the sometimes violent shifts in the country’s government. One of the first films from that country to get wide notice was “Taste of Cherry”, an unexpected Palme d’Or winner at Cannes.

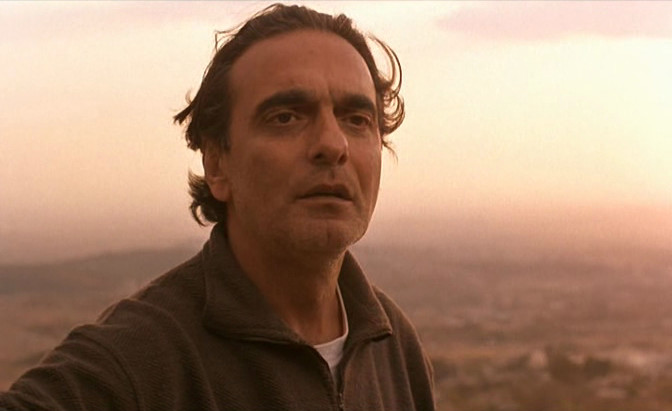

Written and directed by the distinguished Abbas Kiarostami (who had been a noted filmmaker in his part of the world for almost 30 years at the time this film was released), this highly emotional film follows the dark journey of a man named Badii (Homayoun Ershadi) who is driving around Tehran and its countryside in his white Land Rover most purposefully. He is seeking a special man to perform a special job for him. He rejects a number of common day laborers before picking up a soldier and telling him that, for reasons of his own, Badii has decided to end his life but, in accordance with tradition, wants a proper burial after he is dead.

The soldier refuses and runs away and Badii happens on Bagheri (Abdolrahman Bagheri), a museum worker with a sick child who once attempted suicide himself. Without really trying to dissuade Badii, Bagheri waxes on about the simple pleasures in life, such as the taste of cherries.

The filmmaker, who keeps things plain and deceptively simple looking, manages to be both quite emotionally involved but also keeps a distance at times by resorting to a documentary style approach in certain scenes. Kiarostami and his cast and crew also did a lot of improvisation (includes the final scenes after the planned finale was accidentally destroyed in the lab).

This is not a traditionally polished sort of film and may not please everyone but it is heartfelt and expertly made. It is a gateway to a part of the cinematic world relatively few know.

Author Bio: Woodson Hughes is a long-time librarian and an even longer time student/fan of film, cinema and movies. He has supervised and been publicist for three different film socieities over the years. He is married to the lovely Natalie Holden-Hughes, his eternal inspiration and wife of nearly four years.