6. Affliction (1997)

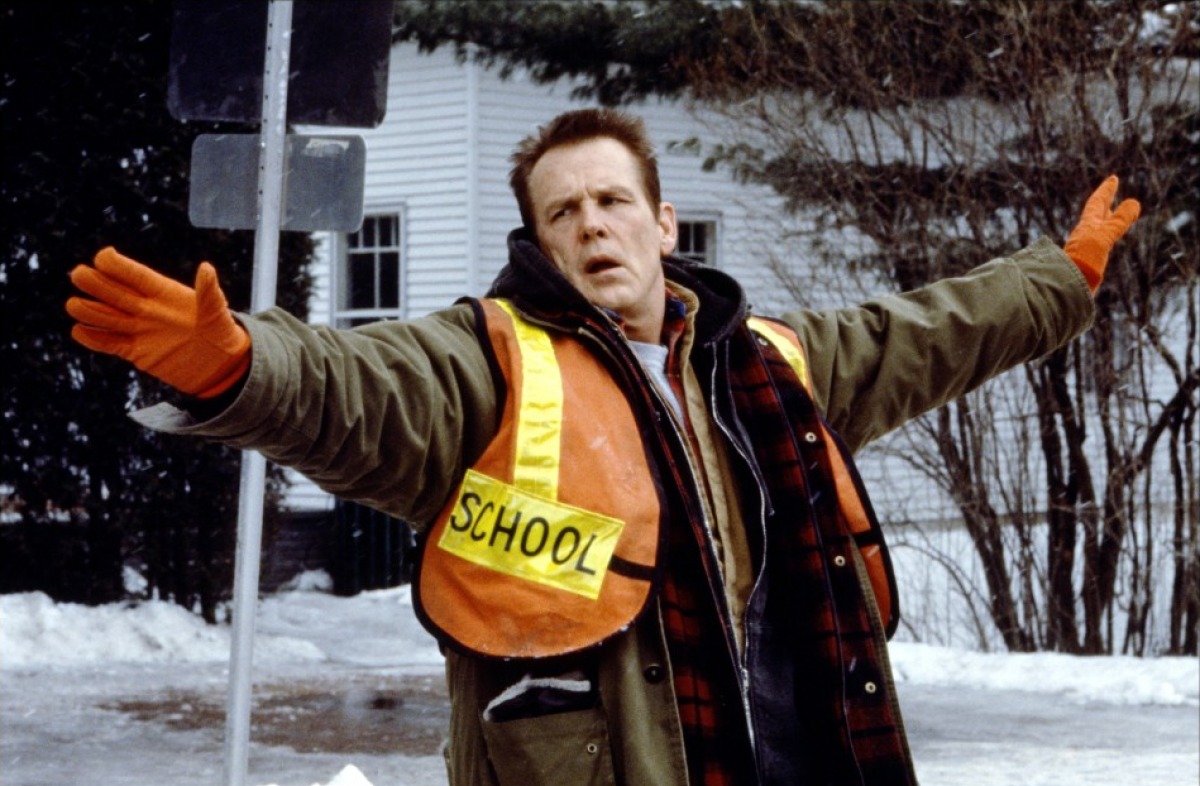

While Paul Schrader’s Affliction was initially met with critical raves and even earned James Coburn a well-deserved Academy Award, the film is barely spoken of these days. On the surface it’s a very somber, contemplative work, perhaps too deliberately paced for some, but deep within this film lurks a fiery rage.

This is a violent picture, not due to gunplay or bloodletting but rather sentiments: Affliction is emotionally violent. Nick Note portrays Wade Whitehouse, a policeman in rural New Hampshire. Raised by a drunken tyrant of a father (Coburn), Wade is emotionally closed-off and has grown detached from many of those around him – most notably his daughter and ex-wife. He lives behind a facade of blue-collar manliness but it’s beginning to crumble; when a fatal hunting accident occurs and he begins to suspect foul play was involved, Wade’s infatuation with the case threatens to break his sanity entirely.

Schrader was at a creative peak in the late 90’s and Affliction could be his most steady, assured work. Elegant cinematography from Paul Sarossy perfectly captures the atmosphere of a bitter Northeastern winter in a way that’s visually impressive but never showy. The vivid flash of Schrader’s earlier works was appropriately toned down for Affliction.

Russell Banks’s score, a mixture of the serene and the discordant, enhances the “trouble beneath tranquility” vibe of the film. His use of a recurring main theme, a technique rarely seen in films anymore, is worth noting here. Nolte, as Wade, gives the impression of a soon-to-explode pressure cooker, or a steam pipe about to blow. Only when we meet his whiskey-drinking, heartless father, Glen, does Wade’s situation start to make more sense. Affliction is a splendid downbeat drama that could use a little more attention.

7. The Butcher Boy (1997)

Few films explore an unhinged mind more successfully than Neil Jordan’s The Butcher Boy, the final production from Geffen Films. The picture stars Eamonnn Owens as Francie Brady, a highly disturbed 12-year-old child raised in a poor Irish household. Virtually ignored by an emotionally absent, unemployed father and a manic-depressive mother, Francie lashes out in increasingly troubling and violent ways.

All of the events in The Butcher Boy are seen through Francie’s eyes, and he (as an adult) narrates the film in a bright, cheery tone that suggests a truly psychotic nature. When the boy does terrible things, his adult voice is always there to explain his reasons, to rationalize and often to make a clever joke as well.

Unusually intelligent for his age, Francie Brady has an undeniable spark that could easily be mistaken for charm – in reality, he’s a highly adaptable sociopath with a natural ability to manipulate and connive.

There must have been some doubt as to whether a child actor could handle such a complex, layered character, but Owens more than handles himself – he gives one of the most remarkable performances from a young actor ever captured on film. Owens dominates this picture, tears through every scene with a ferocious command just like little Francie should. You’ve never seen such a confident thespian under the age of 15.

The Butcher Boy was Neil Jordan’s tenth feature and he handles the material with an unusual tenderness, never allowing his film to become oppressive. He’s a highly underrated filmmaker and The Butcher Boy is his most overlooked film.

8. Happiness (1998)

Between 1995 and 2005, Todd Solondz released four shockingly bold masterpieces – Welcome to the Dollhouse, Happiness, Storytelling, and Palindromes. The second of these, Happiness, is his finest work, but be warned – Solondz explores the seedy underbelly of middle-class suburban America in a way that would make David Lynch blush.

Happiness is a punishingly bleak film that covers subjects (suicide, pedophilia, rape) many find objectionable. The film revolves around three sisters – Joy, Helen, and Trish. Joy (Jane Adams), the youngest of the three, is perpetually single and nurturing a failed musical career; of the three sisters, she’s the black sheep and perhaps the only genuinely nice person in the entire film.

Then there’s Helen (Lara Flynn Boyle), the middle child, a successful author living in New York with an obsessed phone stalker for a neighbor (Phillip Seymour Hoffman). The oldest sister, Trish, has achieved what many consider to be the American dream: a picturesque family, nice home, two-car garage.

Unfortunately, her therapist husband (Dylan Baker) is a monumentally disturbed sexual deviant. Every character yearns for peace of mind, to be content, but the definition of ‘happiness’ varies greatly from person to person; one man’s paradise is another man’s hell. The characters in Happiness desire human connections but we’re constantly reminded that the unforgiving world they inhabit, in addition to their own faults, makes true contentment impossible for them.

Solondz prefers a very low-key visual approach and his films are often scored with sappy, sitcom-style music; he never uses tried-and-true cinematic techniques to tell you how to feel. In fact, he often goes the opposite route and does something to throw you completely off balance. Very few filmmakers would have the cojones to write a script like this and put it out there, and even fewer actors would be willing to participate. A distinctly American classic, Happiness is both unsettling and entertaining, disturbing and occasionally hilarious. It’s worth the effort.

9. Summer of Sam (1999)

You’d be hard pressed to find a major American movie as scatterbrained as Summer of Sam. Powerful, expertly-crafted sequences sit alongside clumsy, awkward ones; it’s profane, violent, sexually explicit, and deliberately, unapologetically messy. Lee’s picture, about the frenzied atmosphere surrounding the Son of Sam murders in 1977, is quite unstable… and that’s precisely what makes it such a resounding success.

Summer of Sam isn’t so much about the crimes (though they are depicted), but rather the infectious mood of paranoia and panic that was stirred up by David Berkowitz that blistering summer in New York City.

Lee largely chose to focus on the lives of those close by: the people of a largely Italian-American section of The Bronx. This was more out of necessity than choice, as the filmmaker was personally facing an extreme backlash from relatives of Berkowitz’s victims. They were loudly protesting the picture, claiming that it would glorify the murderer’s actions.

As a result, Lee’s focus shifted from Berkowitz to several sideline characters, namely a young married couple (John Leguizamo, Mira Sorvino) who are struggling with the husbands infidelity. In addition, there’s Richie (Adrien Brody), a wannabe Brit-punk whose spiked hair and dog-choker necklaces arouse the suspicion of the macho Italian thugs in the neighborhood.

It’s a heady brew of true crime, period piece, and character study, one that admittedly doesn’t always work. While disco-centric scenes set at hotspots like Studio 54 and Plato’s Retreat feel very genuine, Lee’s handling of the punk aesthetic is all wrong; he’s got Richie, a 1970’s punk in New York, wearing spanking-new bondage pants and sunglasses that look like they’re from Pac Sun.

Certain sections carry on endlessly (Sorvino stated that one orgy scene was the most uncomfortable filming experience of her entire career), while others feel truncated, like they’ve ended too abruptly. The film zig-zags so madly from character to character, mood to mood, situation to situation, that the viewer is left with no choice but to sit back, sweat, and hold on for dear life. Somehow, when all is said and done, one ends up weirdly admiring Summer of Sam.

There’s no other movie quite like it. It’s a beautifully performed, highly entertaining work of art, perhaps the most daring of Lee’s whole controversial career. It’s also worth mentioning that John Leguizamo is absolutely electric in this film, has never been better. His marvelous performance, like the entire picture, deserves reassessment. A flawed masterpiece.

10. Another Day in Paradise (1999)

Larry Clark is no stranger to controversy. In addition to years of substance abuse problems (his memory of editing Another Day in Paradise: “I went back on heroin, and my editor was doing coke by the bagful”), Clark has a fondness for extremely provocative subject matter that often involves troubled youths. His all-consuming fascination with young people behaving badly, often in various states of undress, has earned the ire of many critics and filmgoers. Far from discouraging him, this outrage seems to nudge Clark further down the path of excess as he ages.

Those who felt that Kids was creepy and exploitative would probably drop dead if they saw his 2002 effort Ken Park. Clark’s wonky reputation has undoubtedly cast a shadow over some of his less controversial efforts; Another Day in Paradise, a gritty crime drama from 1998, is a perfect example.

Based on a book by Eddie Little, an acclaimed author best known for his “Outlaw LA” column that ran in LA Weekly, the film depicts the lives of two young lovers/criminals named Bobbie and Rosie.

An older, more experienced pair of thieves – Sid (Melanie Griffith) and Mel (James Woods) – take Bobbie and Rosie on the road and the four of them embark on a series of robberies while forging something akin to a family, albeit a highly dysfunctional one. Soon their relatively stable unit begins to crumble under the weight of drugs, resentment, and generally deviant behavior.

While all of the actors bring their best, Woods (who co-produced and, by some accounts, ghost-directed portions of this film) is front and center. You can’t take your eyes off the guy, and Melanie Griffith, a talented actress often relegated to less-than-desirable parts, turns in what has to be the best work of her career as Sid; together they create such a believable chemistry.

Vincent Kartheiser and Natasha Gregson-Wagner excel as Bobbie and Rosie, but Woods and Griffith are who you’ll be watching. While the staggeringly brilliant Bully (2001) remains Larry Clark’s ultimate achievement, Another Day in Paradise runs a very close second.

Author Bio: Derich Heath is a writer, filmmaker, and musician living in Los Angeles. He has made a documentary on the making of Prom Night II and is currently in post-production on his debut feature, Night Owls.