5. Jerzy Kawalerowicz

Best Films: Shadow, Night Train, Mother Joan Of The Angels, Death of a President

In the aftermath of WWII, and following the many atrocities the polish people were submitted to under the Third Reich, there arose a small film school is Lodz. Clearly influenced by both the Italian Neorealist movement and the Socialist Realism agenda, the young filmmakers in Lodz set out to make movies studying the image of the Polish and its general myths, as well as analyzing the ideas of heroism and villainy.

Among such filmmakers there was one Jerzy Kawalerowicz, who would rise to a high platoon in the movement. Kawalerowicz first released a couple of minor films which didn’t garner much attention. It was his 1956 thriller Shadow that gave him notoriety and admiration. Centering on a group of policemen and investigators as they try to piece together the life of a man found dead, Shadow was greatly influenced by Kurosawa’s Rashomon and it was a riveting piece of cinema. His next film, Night Train, also followed this line of tense police drama coupled with social and historical backgrounds.

It was in 1961 that Kawalerowicz released his masterpiece, Mother Joan Of the Angels. Set in 17th Century Poland, Mother Joan follows one Father Suryn as he tries to understand a phenomenon of multiple demonic possessions taking place in a small convent. A deeply unsettling and scary movie, Mother Joan is layered and surprising. Listed by Martin Scorsese as one of the 21 Masterpieces of Polish Cinema, Mother Joan still holds as much impact today as it did when it was first released.

If you can’t get enough of great European cinema, you can’t miss Jerzy Kawalerowicz.

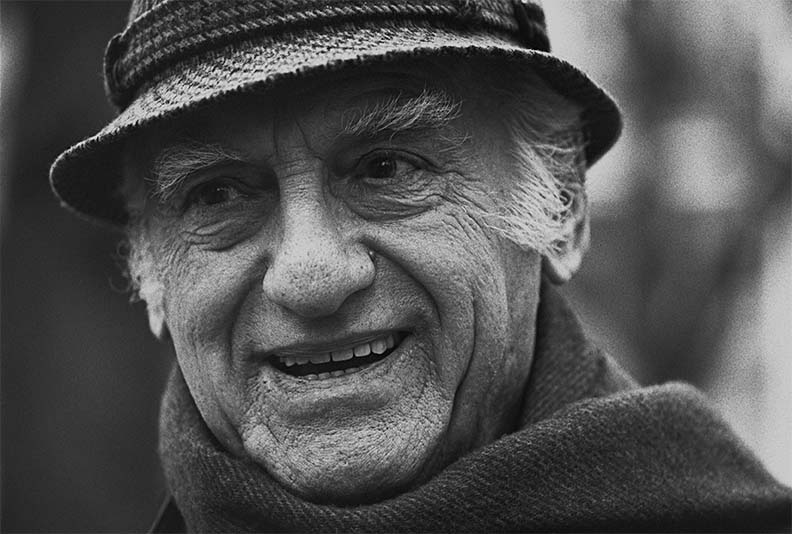

4. Eduardo Coutinho

Best Fims: Cabra Marcado Para Morrer, Babilônia 2000, Meu Santo É Forte, Edifício Master, As Canções

Arguably the most important Latin-American documentarist to ever hold a movie camera, Eduardo Coutinho is known and widely respected in his home country of Brazil. Unfortunately, his fame does not extend overseas.

Starting out his cinematic career as a screenwriter in the 60’s after having studied editing and directing in Paris, Coutinho had it in him to make a fictional movie focusing on the widow of a real revolutionary farmer who had been murdered. However, two weeks into production, Cabra Marcado Para Morrer’s shooting was interrupted by the military coup d’état that established a long period of dictatorship in Brazil, as part of the crew was arrested for suspicion of communism and the film was deemed lost by Coutinho himself.

In the meantime, Coutinho continued writing screenplays for famous films and started working as a journalist, which granted him some economic stability. With the fall of the dictatorial government in 1984, Coutinho quit his journalistic work so that he could dedicate 100% of his energy to filmmaking. At the same time, he discovered that a crewmember had hidden rolls of film shot for Cabra Marcado Para Morrer, and so Coutinho decided to adapt it into a documentary focusing on the 20 years of dictatorship Brazil had just been through.

A superb documentarist with an uncanny knack for eliciting trust and complicity from the people he interviews, and who used silence just as much as speech to elicit emotion, Coutinho’s work is an absolute triumph. From his exploration of religiosity in the slums of Rio de Janeiro (Meu Santo É Forte) to his analysis of urban loneliness (Edifício Master), Coutinho showed the aura of different places and displayed a vast array of characters and people in a beautifully humane manner. His films are a must for any documentary lover out there.

3. Nelson Pereira dos Santos

Best Films: Rio, 40 Graus; Rio, Zona Norte; Vidas Secas; Como Era Gostoso o Meu Francês; Memórias do Cárcere

One of the most prominent and unjustly overlooked figures of the Brazilian Cinema Novo movement, Nelson Pereira dos Santos is by the far one of the most interesting and important filmmakers to have come out of the tropical country.

Born and raised in São Paulo, Dos Santos started out as an assistant director in Rio de Janeiro at the start of the 1950’s. At the age of 27, he shot and released Rio 40 Graus, the first part of a purported trilogy concerning life in the city he claims adopted him.

After the critical success of the first two films of the trilogy (the third never saw the light of day), Dos Santos tried his hand at adapting one of the most celebrated and respected Brazilian novels of all time, Vidas Secas. A far cry from the typical urban analysis his first movies delved into, Vidas Secas follows a family of extremely poor farmers in the Brazilian North-East as they march across a barren land, escaping drought and famine.

Widely regarded as one of the greatest masterpieces of Brazilian Cinema, Vidas Secas brought notoriety and acclaim to Dos Santos, who would continue to adapt Brazilian classics (his adaptation of Graciliano Ramos’ Memórias Do Cárcere won him the Jury Prize in Cannes) and to explore different parts of Latin-American culture and folklore in his films.

A poignant and essential filmmaker, Nelson Pereira dos Santos continues to churn out movies to this very day. Don’t sleep on his filmography, especially if you’re a fan of Glauber Rocha and the new waves of cinema that emerged worldwide during the 1960’s.

2. Ousmane Sembène

Best Films: La Noire De…; Emitaï; Xala; Ceddo; Moolaadé

Ousmane Sembène was a historical figure in both African film and literature. Born in Senegal in 1923, Sembène served in the WWII as part of a special army corps destined to help free French occupied forces. In 1947, he moved to Marseille, France, where he worked at the docks and joined the Communist Party.

Following his return to Senegal, Sembène started writing short stories and full-blown novels, some of which brought him worldwide acclaim and admiration. Concerned with reaching a higher audience than his books ever could hope for, Sembène started his filmmaking career by adapting some of his own shorter literary works. It was his first feature film, La Noire de… that granted him critical praise and brought international attention to African cinema.

Sembène was a filmmaker preoccupied with his own history and culture. The first sub-Saharan director to ever release a film, and the first to produce a movie spoken in the Wolog tongue, Sembène was a brave visionary who wasn’t afraid to explore uncomfortable subjects. A lot of his work delves into the hardships of black people submitted to racism (something he experienced while working in Frances) and analyses pieces of African religious culture. His 2004 Moolaadé concerned the controversial practice of female genital mutilation, while his adapted-from-his-own-novel Xala dealt with economic inequality and sexual dysfunction.

Sembène was also known for his vicious attacks on the corrupt elites that arose in Africa during the 1960’s and for his critique of French-African bourgeoisie. A bold and seminal filmmaker whose films and novels are shamefully ignored by most non-African societies, Ousmane Sembène is a man that deserves closer attention and wider respect.

1. Corneliu Porumboiu

Best Films: 12:08 East of Bucharest; When Evening Falls in Bucharest or Metabolism; Police, Adjective; The Treasure

The Romanian New Wave of cinema has brought us many masterpieces from extraordinary directors. Cristian Mungiu’s three films have all won major awards in Cannes, Cristi Puiu’s The Death of Mr Lazarescu was one of the most awarded movies from the 2000’s not spoken in the English language, and even Cristian Nemescu tragically short-lived career was extremely lauded.

A Romanian auteur few people remember to mention is Corneliu Porumboiu, despite his debut feature film 12:08 East of Bucharest having nabbed him the Caméra d’Or at Cannes. As a matter of fact, all his movies which were exhibited in Cannes won important awards at the festival, and that is certainly no mean feat.

An explorer of genres and formats, Porumboiu has made dramas, comedies, and police thrillers. He has shot fiction and documentary, and has delivered heart-wrenching contemplative films – the amazing When Evening Falls in Bucharest or Metabolism is a prime example – as well as more light-hearted and sweet movies, such as The Treasure.

His incredible flexibility as a filmmaker is what makes him such an extraordinary talent, as he is able to hop between genres at ease and displays ability to introduce poignant social and historical commentary (one of the key staples of the Romanian New Wave) into completely different types of films.

As difficult as it may be to pinpoint why certain filmmakers are more popular than others, Corneliu Porumboiu remains one of the most exciting European movie directors currently working, and it’s high time we give him some well-deserved consideration.

What are other great filmmakers you think people don’t give enough attention to? Give us some movie recommendations at the comments section below!

Author Bio: Fernando Pompeu is unashamed to admit he loves Batman and Robin. He just tries to hide that information behind a lot of Bergman and Tarkovsky films. He also has a small production company.