6. The Legend of Suram Fortress (Sergei Parajanov & Dodo Abashidze, 1985) / Soviet Union

“The Legend of Suram Fortress (Ambavi Suramis tsikhitsa)” is Sergei Parajanov’s first film after 15 years of strict Soviet censorship and government persecution. Stylistically close to his masterpiece “The Color of Pomegranates (Sayat Nova)”, it could easily be described in only three words – pure cinematic magic.

An adaptation of an ancient Georgian folk legend recorded by Daniel Chonkadze in the 19th century, it recounts a simple, yet evocative story of love, captivity, sacrifice, commitment and fate’s fickle ways which is set in turbulent times and primarily told via the enthralling tableaux vivants. Broken by several digressions linked to certain events and/or characters, the poetic narrative is a “deeply personal metaphor for (Parajanov’s) spiritual imprisonment, exile, and martyrdom” as Acquarello puts it in the Strictly Film School review.

Initiated by a medieval monarch fearing an enemy attack, the building of the titular fortress proves to be an insurmountable task, because the walls – held by a quaint “plaster” of hay and eggs – keep crumbling down. As we later learn from a heartbroken fortune teller, Vardo, a blue-eyed youngster must be voluntarily bricked up alive in order for the stronghold to stand and it turns out to be her ex-lover Durmish-Khan’s son Zurab.

The tragedy plays out in the bittersweet atmosphere of uncertainty, in bright and vast open spaces contrasted by dark, claustrophobic interiors of a church and diviner’s home.

Beautiful, frequently symmetric compositions of dreamlike and mystical quality juxtapose humans, animals and various artifacts in an almost ritualistic way, resembling a traditional tapestry with plenty of arcane details weaved in. Unless you are well-versed in Georgian folklore, you are likely to get lost in this exotic fantasy, but don’t worry – you’re in for a truly unique experience.

7. In a Glass Cage (Agustín Villaronga, 1986) / Spain

In addition to being one of the most unnerving horror dramas ever put to screen, “In a Glass Cage (Tras el cristal)” is also one of the strongest feature debuts. Agustín Villaronga pulls no punches in bringing to life a dark tale of a former Nazi doctor and child molester, Klaus (Günter Meisner in a handicapped role), and his survived victim turned psychopath, Angelo (the exceptional first time performance of David Sust who will return in Villaronga’s “Moon Child” and disappear from the scene after 1990).

The disquieting prologue which sets the mood for the rest of the film sees Klaus trying to commit suicide after killing a naked, wounded, suspended, probably raped and barely conscious boy in the basement, unaware of prying eyes. Several years later, he is paralyzed and confined to an iron lung with glass sides and taken care of by his distressed wife Griselda (played by “the Almodóvar girl” Marisa Paredes) and their pubescent daughter Rena (Gisèle Echevarría).

One day, Angelo arrives in their (remote) house in Spain and blackmails Klaus into taking him as a nurse, despite Griselda’s instant (or rather, instinctive) animosity toward the young man. Gradually, it is revealed that Angelo’s devious plan involves something much worse than revenge…

“In a Glass Cage” is not nearly as explicit as some torture porn or Pasolini’s “Salò” which it is often compared to, and yet Villaronga’s portrayal of human evil and depravity, as well as of descent into madness is so dismal, harrowing and psychologically (in)tense that you want to scream in terror. To call it nightmarish and/or claustrophobic would be an understatement, as it mostly takes place in Klaus’s villa of deep shadows and icy blue tones which make the controversial proceedings all the more eerie and suffocating.

8. Tales from the Gimli Hospital (Guy Maddin, 1988) / Canada

Shot in boxy 4:3 format and playing like a peculiar cross between a silent movie and an early talkie, Guy Maddin’s feature-length debut is definitely one of his least talked about offerings. Possessing all the stylistic traits that its creator has been instantly recognized for in years to follow it, “Tales from the Gimli Hospital” is the most outré and incomparable entry of the list.

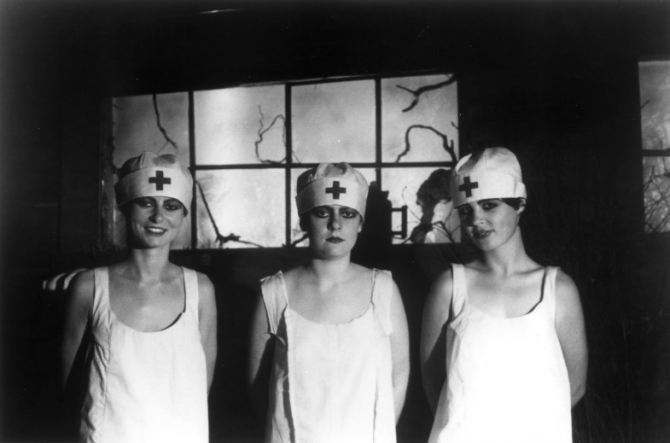

In the titular institution, two children are called by their mother’s deathbed and told a bizarre tale by their Icelandic grandmother, one of a lonely fisherman, Einar, and a widower, Gunnar, who meet in the Gimli of yore (which serves as a stable and a henhouse as well). Between the two men who are both admitted for an unspecified disease, a rivalry is born, for Gunnar is popular with the nurses, whereas Einar is constantly ignored. Their own stories intertwine in the most surreal ways possible, leaving you scratching your head.

In a nonstop barrage of arresting, beautifully composed pictures, we witness wide array of bizarre occurrences, such as a fire extinguished with a fresh milk or a medical intervention with a scythe as a substitute for a scalpel, during a puppet show instead of an anesthetic. As the wounds are treated with dead seagulls and skirmishes are solved through traditional Icelandic wrestling, we sink deeper and deeper into Maddin’s oneiric, darkly humorous visions.

Retro musical intrusions and intentionally out-of-synch voice-overs complement the dreamlike (and nightmarish) imagery which breaks from B&W to pink-tinted for the operatic sequence of Gunnar’s hallucination. No cutting with Snjófridur’s special scissors is necessary for this little gem.

9. My Twentieth Century (Ildikó Enyedi, 1989) / Hungary | West Germany | Cuba

Not the best, but saved for last is another debut, this time by the Hungarian helmer Ildikó Enyedi. “My Twentieth Century (Az én XX. századom)” is a whimsical ode to the cinema and technological advances from the beginning of the last century.

Focused on the twins, Dóra and Lili (the lovely Dorota Segda in her magnetic first-time, dual-role performance), this enigmatic, slightly surreal dramedy opens in 1880 New Jersey, on the eve of Edison’s unveiling of a light bulb which coincides with the girls’ birth. Several years later, we see them as the doubles of H.C. Andersen’s tragic heroine with the matchsticks.

While asleep in the snow-covered street and dreaming of their late mother and a donkey, they’re adopted by two aristocrats. On December 31 1900, sisters travel by the Orient Express, separated by class and attitude – Dóra as a pleasure-seeking libertine and Lili as an uptight feminist revolutionary. Will they cross their paths after both meeting a mysterious man, Z (Oleg Yankovskiy), and more importantly, where will their paths take them?

Intertwining two narrative threads into an elusive, non-sequitur whole and poking fun at machismo, as well as the female empowerment, Enyedi demonstrates her quirky sense of humor and a keen eye for compelling visuals. The high-contrast B&W photography reflects the siblings’ disparity and the way the jovial auteur approaches each one of them.

But what is the meaning of the bouncing Moon from the stylish intro, a chimpanzee’s confession or the stars speaking, singing and projecting a film for a dog who escapes an experimental lab? Does it even matter when what you’ve seen is, simply put, delightful?

10. Neo Tokyo (Rintarō, Yoshiaki Kawajiri & Katsuhiro Ōtomo, 1987) / Japan

Although it’s less than fifty minutes long, “Neo Tokyo (originally, Meikyū Monogatari which is literally translated as Labyrinth Tales)” makes a lasting impression on the viewer. Considered an essential viewing by many anime connoisseurs, this sci-fi anthology – the adaptation of short stories by Taku Mayumura – showcases the unrestrained creativity of its authors.

The first, wrap around segment “Labyrinth” is one of the most experimental works by Rintarō who seems pretty unbothered by the limited time frame. A game of hide-and-seek between a girl, Sachi, and her cat, Cicerone (which is an old term for a museum and gallery guide, by the way), takes the duo into a gloomy wonderland, after they pass through a secret doorway behind a grandfather clock.

Various supernatural eccentricities and weird characters to be found there, such as ghost-children, working class citizens transforming into black liquid or a train driven by a glowing apparition, are exquisitely depicted in Atsuko Fukushima’s unusual artwork and vivid animation accompanied by the eclectic score which ranges from classical to droney. Part homage to silent film and part surreal phantasy, “Labyrinth” ends with a “gimmicky” link to the following segment(s).

“The Running Man” (not to be confused with the eponymous live-action feature starring Arnold Schwarzenegger) is designed, animated, directed and written for the screen by Yoshiaki Kawajiri who will come into prominence with “Wicked City” and “Ninja Scroll”. Presumably inspired by “Death Race 2000”, it is a spiritual predecessor to Takeshi Koike’s “Redline” and an idiosyncratic, aesthetically memorable blend of cyberpunk, racing film and supernatural thriller.

Its (anti)hero Zach Hugh is the unbeaten champion of so-called Death Circus – a futuristic racing event witnessed by thousands of spectators who bet on the lives of the competitors. Together with a noir-esque reporter and the narrator, Bob Stone, who is sent to interview the champ, we learn of Zach’s telekinetic abilities and watch his last, death-defying “performance”, as Kawajiri’s detailed and violent visuals command our attention. Despite its age, this vignette still holds well today.

And the last, most wordy and longest part of the omnibus is Katsuhiro Ōtomo’s directorial debut “Construction Cancellation Order” – a cautionary, somewhat satirical tale of man’s overdependence on technology. It follows a snooty, nervous white-collar worker, Tsutomu Sugioka, who is sent to a fictional South American country of the Aloana Republic to stop the completely automated build-up of Facility 444. What he finds there could be labeled as the robot-ruled hell for civil engineers.

Boasting spectacular animation and bearing the markings of Ōtomo’s aggressive drawing style, this inferno of steel contraptions, intricate pipelines and entangled cables incessantly huffs and puffs and increases Tsutomu’s annoyance. The bright color palette and Grieg’s soothing “Morning Mood” are both used to great ironic effect.

In the carnivalesque conclusion, we are treated to a little bit more of Rintarō and Fukushima’s wild imagination instilled into the loony imagery.

Author Bio: Nikola Gocić is a graduate engineer of architecture, film blogger and underground comic artist from the city which the Romans called Naissus. He has a sweet tooth for Kon’s Paprika, while his favorite films include many Snow White adaptations, the most of Lynch’s oeuvre, and Oshii’s magnum opus Angel’s Egg.