It can be easy for one film to dominate discussion surrounding a certain filmmaker: when they create a perfect masterpiece, their other work, no matter the quality, can be overshadowed.

Films of absolute precision shouldn’t detract from other masterful efforts by directors, and the following list looks at 10 such examples. Each film is a masterful entry in the filmography of their creator and, while not reaching the pantheon of more lauded films, deserve greater recognition than they receive.

1. Old Joy – Kelly Reichardt

A work of transcendent minimalism, Kelly Reichardt’s Old Joy (2006) feels like a truly American film in its own quiet way. A road film based on a short story by Jonathan Raymond, the film follows two old friends, Mark and Kurt, as they reunite over a camping trip in the Oregon wilderness. The characters both represent different paths: Mark has settled down and is on the cusp of fatherhood and all the responsibilities that entails; Kurt is living a nomad existence, a pot smoker with no seeming clear direction forward.

The film is ostensibly about friendship and loss of connection over time. Reichardt surrounds this narrative with simple but beautiful shots of the natural landscape, allowing it to become a character as any good road film should: wide blue skies, lonely farmhouses and lurching green treetops envelop their car as they leave Portland behind. Accompanied by a soundtrack by Yo La Tengo, the overall effect is incredibly meditative.

There is much subtext to Old Joy, too. Coming so soon after the monumental Brokeback Mountain, it would be impossible to escape allusions to a romance lurking beneath the surface of the two men’s camping trip, and it does seem as if Kurt holds genuine, unreturned, affection for his friend.

This is highlighted in a scene at the springs, when he gives Mark a shoulder massage: we see Mark’s face drowning in pleasure and relaxation, and the shot lingers on him in the water. It’s a deeply homoerotic sequence but Reichardt doesn’t demonstrate anything further about their relationship; it’s only hinted at, and could perhaps just be a tender moment between two sensitive souls trying to reclaim their old rapport.

Politically speaking, Reichardt shows Mark listening to Air America, a liberal station, on his return home from the trip as the voice discusses the state of contemporary times in the Bush era. This return to his cozy, progressive world seems like a comfort blanket after the wild and adventure of his weekend: America may be in a bad way but it’s only for him to worry about in a state of static despair. Kurt, then, is presented as the challenge to the conservative way of living, a character not content to settle for the systematic ennui.

That Reichardt finishes her film focusing on Kurt, alive and floating along the city streets, conveys that there still exist those who haven’t given up on their ideals, despite any hardships or struggles they may encounter. Old Joy is a quiet paean to a different kind of cinema. Reichardt’s natural and thoughtful approach was welcome in 2006 when it was released, and is certainly still welcome today. It’s meandering pace allows the viewer to find their own meaning in the pauses and silences and is testament to an underused mode of filmmaking.

2. Le Bonheur – Agnes Varda

A fierce creation of the French New Wave female warrior Agnes Varda, Le Bonheur (1965) is a colorful, striking film that still holds many possible readings today.

The film opens with an idyllic portrait of a modern, happy couple, very much in love, with two young children (the family structure is occupied by a real-life equivalent, in actors Jean-Claude and Claire Drouot). They are seen in moments of splendor and affection, enjoying their time together, having picnics and going on walks in nature. The happiness shown, as constructed in Varda’s sensuous color scheme, recalling the Impressionist painters, seems to be too perfect and soon enough it is broken.

The husband Francois begins flirting with Emilie, a young woman who works at a telegram office near to his workplace and soon they begin engaging in an affair. He maintains this relationship while remaining in his happy home and Francois soon realizes that, for him, by being in love with two women only increases his joy in life; he can experience the best of both worlds, due to the women’s differing personalities.

Varda, in the character of Francois, doesn’t create a one-dimensional male. He isn’t the archetypal brute committing infidelity; rather, while he cares wholly about his own ego and happiness, he is also shown to be a kind and loving man. Upon being told about the affair, his wife Therese is soon found dead as she can’t live with the news.

Le Bonheur is an unflinching and complex look at love. Varda offers us no easy answers regarding the provocations on screen. Arriving as it did in 1965, it can be seen as both a critique and ironic support of ‘free love’: is this world dystopian, with male domination and the females being wholly interchangeable, or is it a kind of utopia, where love can be given freely and impulses can be followed to their fullest?

Ultimately, it feels like a damnation on the era of free love, while acknowledging its deep appeal. The film is also an intensely feminist work, reflecting the period. Varda’s film feels like an example of ‘consciousness raising’, encouraging her fellow women to refuse to be silent and act in their own interests. Le Bonheur closes with an image of Francois’s happy family, this time with his new wife Emilie, walking away from the camera through a beautiful wooded area, and it’s unclear if this scene is idyllic or something worse.

3. Paterson – Jim Jarmusch

Jim Jarmusch is a director with achingly hip and cool credentials, but Paterson (2016) feels like a quietly personal entry in his filmography. It concerns a bus driver named Paterson, also a poet, for seven days as he goes about his usual routine: we see him go to work each morning, write poetry on his lunch break, return home to his loving wife Laura, before walking his dog Marvin and having a drink in his local bar. Jarmusch makes us intimately aware of this man’s simple but pleasant existence.

The plot is miniature in scale, and each part feels like a well-constructed stanza. There is great rhythm to the piece: Paterson notices occurrences of twins around town; he meets other poets, like a young girl, a rapper he notices in a laundromat, and a visiting Japanese man; he enjoyably overhears interesting exchanges between the passengers on his bus.

Moments of action occur too – Paterson’s bus breaks down and a lovelorn man brings a gun to his local bar – but these last only briefly before the return to his daily routine; like conflicts at the end of stanzas which nontheless never threaten to overcome the steady flow of the piece. ‘Paterson’ is both the name of the main character and the film’s location, another small moment of duality.

An industrial town in New Jersey, Jarmusch makes us aware of its surprising cultural history, it being once home to Lou Costello and Fetty Wap, and poets like William Carlos Williams and Allen Ginsberg (indeed, Williams is well known for his epic poem about the city). Poetry is inherently infused in Jarmusch’s film. As Paterson writes his little poems, they appear on our screens, allowing us to absorb their words.

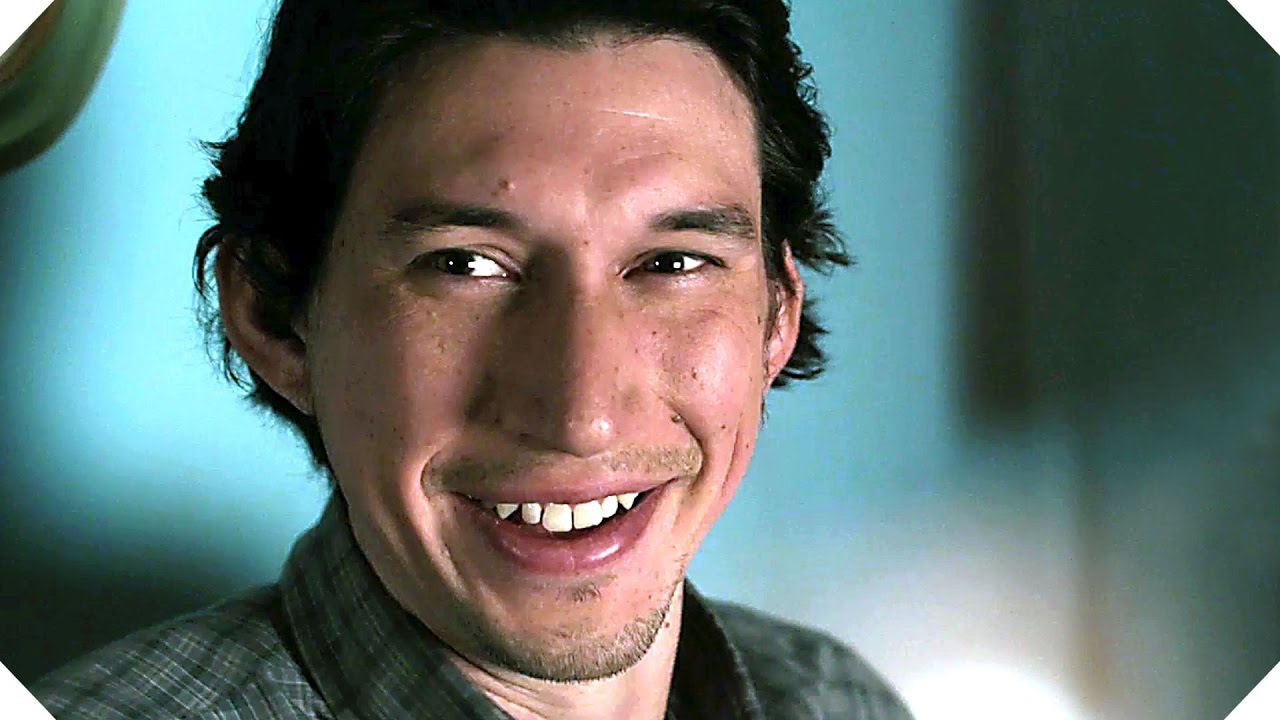

A favorite poet of Jarmusch, Ron Padgett, provides several new works for the film which are attributed to Paterson. Adam Driver gives a genuinely kind and soulful performance as lead character: coming off the back of his starring turn as Kylo Ren in Star Wars, there is the sense that Driver feels a real connection with this character.

It’s very much Jarmusch’s film, though, and despite replacing ironic detachment for warm sincerity, none of his flair for offbeat and profound dialogue is lost. By capturing the contentment which can be found in living a small but pleasant life, Paterson feels like a work of transcendence: it finds beauty in the everyday, locates deeper meaning in the littlest things, and becomes a work of pure poetry in itself.

4. Shame – Ingmar Bergman

An lesser heralded film by Ingmar Bergman, Shame (1968) is something of a curiosity in the great Swedish directors’ work. For one, the conflict of the film doesn’t derive from inner psychological issues that his characters usually contest with, but rather from an external force, that being the force of war on people who didn’t necessarily ask for it. The existential crisis felt this time emanates from bombs and warfare as the characters become mere pawns trying to survive.

The film also came at a point in Bergman’s career when his entire raison d’etre was being questioned: many critics were increasingly calling out his obsession with portraying the lives and ailments of the privileged people, and there was the suspicion that Bergman had lost any social awareness that he once had. Shame, then, feels like a surprising riposte to these critics; indeed, he expressed in interviews around this time his desire to reconnect with the contemporary world in a more general sense.

The film follows a musician couple, Eva and Jan, who became caught on an island in the middle of the outbreak of war despite wanting nothing to do with it. Amidst the ensuing fighting, they are rounded up, first by one side who supposedly ‘liberate’ them, then by the other, who view them as traitors. It’s a darkly comic scenario; war, to Bergman, seems incredulously ambiguous.

Not a war film in the normal sense, Bergman wanted to highlight the struggle for the people caught up in grander fighting and his brutal depiction of Eva and Jan’s disintegrating relationship conveys this. Their personalities swiftly begin to change over the course of the story: Eva grows more impatient and frustrated, especially with Jan’s handling of the situation; Jan, a seemingly nervous man, is badly influenced by the violence surrounding him and by the end appears on the verge of insanity.

The change in the protagonists shows that war doesn’t care for individuals and their relationships, and this way, the film depicts a universal war, one which destroys everything and everyone in its path. That’s why Bergman never reveals the identities or the politics of those fighting; it’s immaterial.

The film ends in a startling scene when Eva and Jan occupy a refugee boat whose motor fails and, wading through a sea of dead bodies, one passenger kills himself by lowering himself overboard. It’s an apocalyptic end: any source of hope and calm previously shown in the film appears lost to the war and its all-encompassing evil. Shame isn’t as discussed as Bergman’s other work, perhaps owing to more formalist presentation: there is no surreal narrative like in The Seventh Seal (1957); there is no challenging stylistics like in Persona (1966).

The more straightforward approach, however, works to great effect in presenting his thoughts on war. Shame stands alone as a sadly accurate depiction of the loss of humanity under wartime, and whether one reads it as an angry rebuttal of the Vietnam war which occured at the same time of the film’s release, or of a depressing reflection on the ‘shame’ of a God figure who would allow this to happen, Bergman created a genuinely political work, a thoughtful but bleak consideration of the era’s society.

5. The Devil, Probably – Robert Bresson

His penultimate feature film, Robert Bresson’s The Devil, Probably (1977) feels like the work of an ageing artist, worn and weary, surveying the new world around him and creating his own conclusions. Its ending predetermined, the film opens with a newspaper headline telling of the death of its protagonist Charles, a disillusioned Parisian youth.

We then are shown in flashbacks the events leading up to his demise, as he cannot find solace or comfort in the worlds of religion, politics, psychoanalysis or love. His choice seems like an exhausted intellectual decision; modern society, for Charles and others like him, holds nothing to stay for. It’s a hopeless, despairing existence which Bresson depicts.

Some documentary footage is included and the devil from the title seems to thrive here, insidious in the earth: present in the environmental pollution of oil s and nuclear tests; present in the destruction of nature, when we see a baby seal being clubbed to death. Clearly, Bresson doesn’t allow for sentiment: there is no attempt to romanticize Charles as a heroic soul not long for this ruined contemporary world.

The resulting feeling is of a truly pained individual, not a clichéd melancholic character. There is no music in the soundtrack to highlight the drama of his decision. Coming at the end of his filmography, Bresson’s famed ascetic style feels close to his end goal for it and everything feels entirely, intricately controlled.

Consider the great set piece when Charles and his eco-activist friend ride the bus: as they discuss society and what’s happening, Charles asks “who is really in charge?” as many of the other passengers interject too. The driver at this point becomes distracted and loses control of his vehicle, causing it to crash.

The scene is interspersed with idiosyncratic cuts to the hands of people getting off the bus and the machinations of the exit door; the whole thing is a perfect encapsulation of the Bressonian style. After crashing the bus driver proceeds to leave the bus while the vehicles around beep their horns furiously. This scene also emphasizes the overall sense of predestination and pointlessness; this event is just another one on Charles’s journey to the end.

The Devil, Probably, surprisingly, has never been cited as one of Bresson’s greatest works. Perhaps this owes to its positioning as one of his later films, as most attention is given to his masterful run of works from A Man Escaped in 1956 to Mouchette in 1967, as well as its cold and confrontational themes, distressing even for him. The film is, though, a powerful watch, whether as part of his wider oeuvre or viewed on its own. A forceful and pulsating indictment of a changing and broken world, it feels equally resonant now as it did upon release in 1977; Bresson truly created a timeless picture.