5. Mishima: A Life In Four Chapters (1985, dir. Paul Schrader)

To mastermind an indescribable, singular experience in any art form is a difficult task unto itself, but to do so with a subject based in real life and on true events can prove maddening, as creativity and reality, while not incompatible, can present difficulty linking. Paul Schrader not only masterfully pulled this arduous task off, but gave the world what may be the most original and unconventional biopic in the history of film with Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters.

The subject: Yukio Mishima, renowned Japanese writer whose life and death is equally as fascinating as, if not more than, his work. Mishima, in a nutshell; a political idealist and strong believer in the samurai code, Mishima’s final chapter would be defined by a coup and subsequent hara-kiri.

It would probably take more effort to make a subpar movie around this material than a good movie, and Paul Schrader not only made a good movie, but went the extra mile. The film utilizes three different color schemes to separate the different chapters of Mishima’s life: in modern day, realistic, insignificant colors are presented; crisp black and white for his formative years; and as for the most unique parts of the film, lush and vibrant colors paint the adaptations of Mishima’s literary output.

This is the most interesting part of the film; key moments of some of his most famous books are presented on screen (with amazing sets alongside the beautiful colors) as an attempt to further understanding Mishima, as sometimes to understand the artist, one must understand their art.

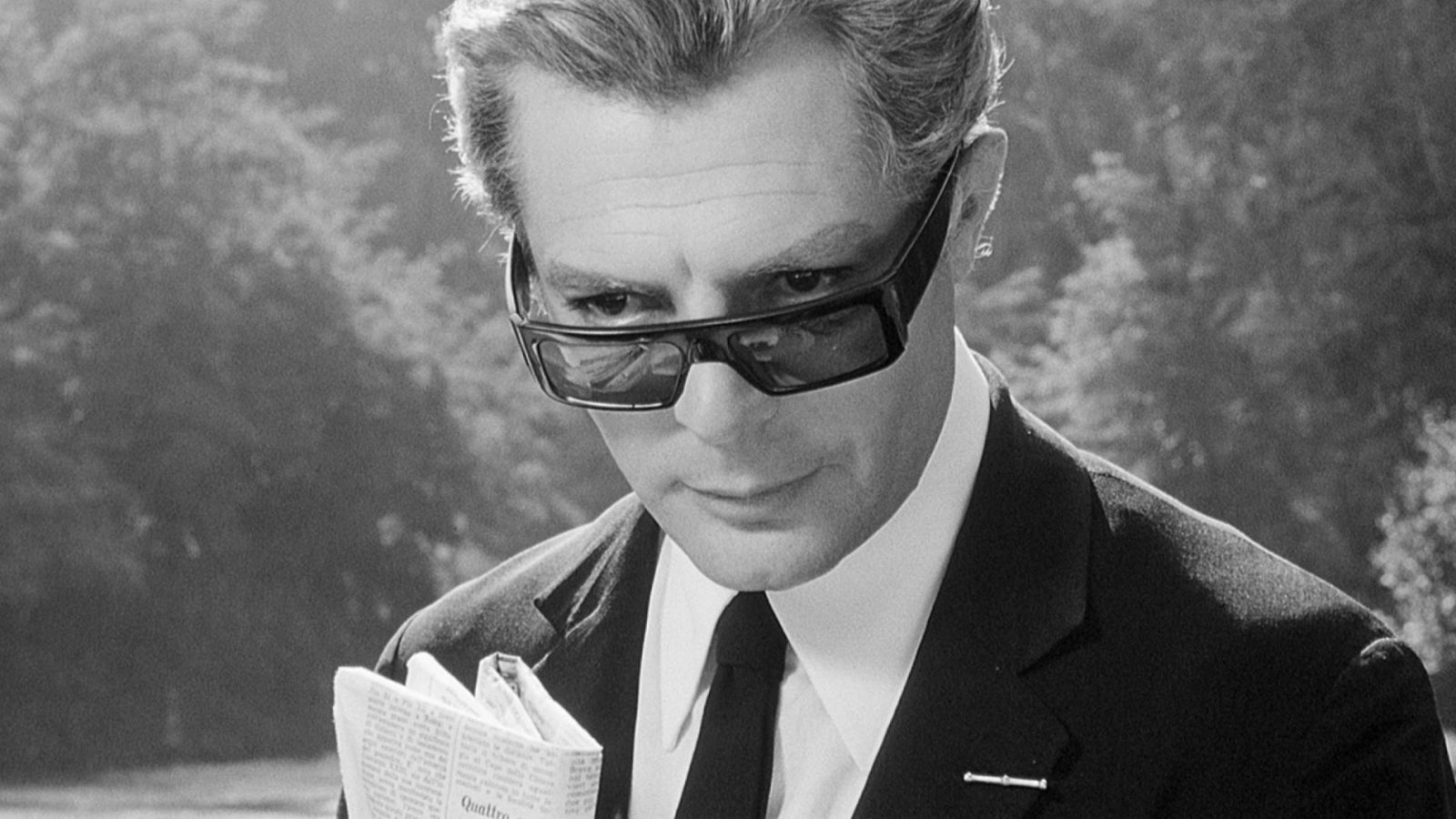

4. Last Year At Marienbad (1961, dir. Alain Resnais)

A landmark of the French New Wave, Alain Resnais gave the world this frustrating yet all too alluring experience of a movie. He treaded the waters of peculiarity to worldwide acclaim with Hiroshima mon amour. With his follow-up, Last Year at Marienbad, he went from treading the waters to confidently diving head-first without hesitation.

He tells her they have met before and they agreed to meet one year later. She has no memory of this man or this exchange whatsoever. 94 minutes later, there is no resolution, no answers, nothing. Only further mystery.

Perhaps the reader may be a little upset, given such a short synopsis, a standpoint that is totally understandable. As soon as said viewer watches the film for themselves, it will become evident very quick: (intentionally) little plot gives way to an extraordinarily enigmatic tone that will only proceed to hypnotize the viewer. An elegant manor becomes a maze as the camera traverses from corridor to corridor. Voices narrate throughout, expressing unsure recollections and subsequent confusion – the kinetic pipe organ that perpetuates throughout only further emphasizes the mystery (a somewhat disturbing yet incredible score by Francis Seyrig).

The result is the cinematic equivalent of a jigsaw puzzle. A fair analogy, perhaps. A frustrating puzzle? Absolutely. Whether or not it can be fully assembled, it is definitely a puzzle worth starting.

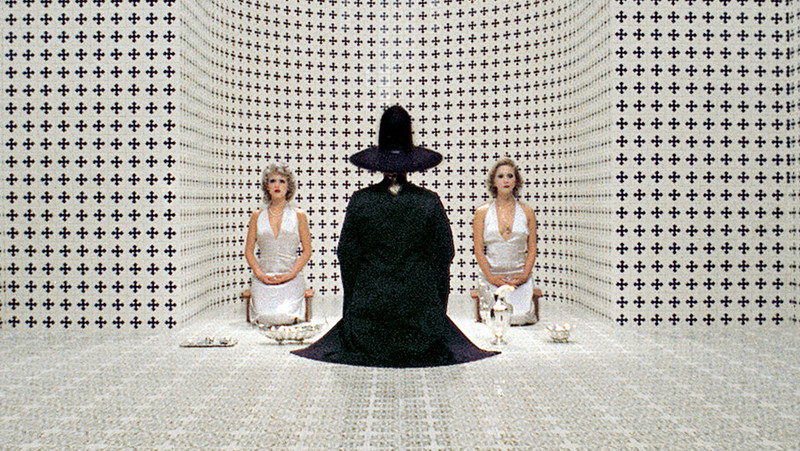

3. The Holy Mountain (1973, dir. Alejandro Jodorowsky)

Whether this is Alejandro Jodorowsky’s masterpiece or not is very much up for debate, as his other works – most notably El Topo and Santa Sangre – are all excellent works. There is no denying, however, that The Holy Mountain is a landmark in the world of avant-garde movies.

The Thief, a naked, bearded man (resembling Jesus Christ), ascends from a mucky cesspool in the middle of a desert and enters a city to bear witness to the outrageously exaggerated – yet all too truthful – absurdities of contemporary society. The Thief soon enters the realm of the Alchemist (portrayed by Jodorowsky himself).

Along with the Thief are seven people, personifications of the planets who embody the spirit of materialism and are in some way responsible for the enablement of society’s absurdities. The Alchemist leads them to leave behind their possessions, burn their money, and joins them on an adventure to the “Holy Mountain”, a physical place where those that reach it become enlightened.

It is a difficult plot to synopsize, and it is, quite honestly, a disservice to the viewer. The Holy Mountain is a film that demands to be seen to be believed. With themes and a story centered on the abandonment of materialism and the idea of the self in zany, multicolored psychedelic temples, The Holy Mountain is perhaps the cinematic definition of “psychedelic”, not just in visuals but in attitude as well. All topped off with an ending that delivers a complete obliteration the Fourth Wall (one of the most incredible uses of the technique), The Holy Mountain is one hell of a trip.

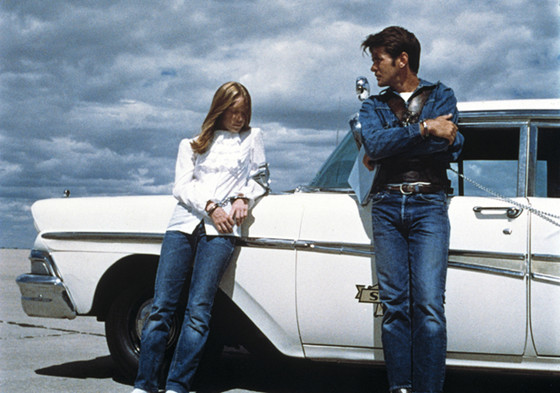

2. Badlands (1973, dir. Terrence Malick)

For those looking to get into Terrence Malick and wondering where to start in his filmography, look no further than his remarkable ’73 debut, Badlands. Not only are most of his defining trademarks present, but it is undoubtedly his most accessible film in a catalog of work that has proven rather polarizing. How ironic that Badlands might also prove to be his most unusual film.

At its core is a serial killer/road trip film (inspired by the killing spree of one Charles Starkweather), simple as that, but this description does the film no justice whatsoever. Badlands follows the murderous and romantic exploits of Kit (Martin Sheen) with his girl, Holly (Sissy Spacek), in the passenger seat.

Without the slightest bit of sympathy or hint of justification for their actions, Malick takes two characters who would otherwise be labelled ‘evil’ and depicts them as what seem like bored and naïve youths – and how interesting that there’s no implication of the dangers of directionless and nihilistic youth (or something along those lines thematically). As morbid as it is, there’s a sort of beauty to it all. Speaking of beauty, the two traverse the American Midwest, and the audience is treated to some of the most beautiful vistas in the history of cinema, all to the lovely score by George Tipton, which would be homage in Ridley Scott’s True Romance some 20 years later.

All this beauty, and how ironic for it to be found in a film about a man’s killing spree.

1. 8 ½ (1963, dir. Federico Fellini)

It’s a cliché to say this, but what is there to say about Fellini’s magnum opus that hasn’t already been said? After the massive success of La Dolce Vita, there was a three year silence from Fellini due to a creative block. Already recognized at the time as one of the greatest filmmakers, Fellini found himself frequently pestered by various parties awaiting his next masterpiece. Well, here is a situation where the wait was definitely worth it; his follow up to his previous masterpiece is not only one of the best films ever made, but it is also a near-perfect portrayal of the complexity of artistry.

Just like Fellini himself, [Italian cinema] regular Marcello Mastroianni is filmmaker Guido Anselmi, who is suffering from a severe creative block and losing interest and passion in the craft – just in time for the approaching production of his upcoming film. As his ideas are criticized and the pressure mounts, Guido sets off into whimsical abstractions that propel inner reflections, ultimate fantasies, and, perhaps, some sort of creative spark.

Even in 1963, artistry and creativity was not a particularly new idea for cinema, but what Fellini did was extraordinary for its time (hell, even to this day): 8 ½ isn’t concerned so much with telling the story of artistic frustrations as much as it is trying to physically depict said frustrations onto the screen, and, oh boy, did Fellini nail it. The mounting pressures and stress are so well conveyed that the film will demand a cigarette break from the audience. And then there’s Guido’s inner retreats into the metaphysical, abstract realms that define the inner complexities of any artist that only Fellini could concoct. A quick reminder that 8 ½ was released in 1963; name any other film that had this much imaginative ambition.

Author Bio: Jakob Miller consumes oxygen in Tucson, Arizona, where he enjoys donning Tripp NYC in 100+ temperatures, practicing off-putting stoicism, and enduring Whitehouse at obscene volumes on a daily basis. He also likes movies.