For any cinephile, there is nothing more exciting than an independent film. With a scene that is comprised of ambitious filmmakers eager to push envelopes (and buttons, sometimes) and free from complete studio control, the possibilities of an independent film are endless, and the viewer is usually guaranteed to see something they never thought possible in a movie. Below, one will find 10 great examples of fearless independent filmmaking.

1. Faces (1968, dir. John Cassavetes)

It was crazy. A respected actor like John Cassavetes setting out to make a film that sounds this uninteresting, a realistic examination of a crumbling marriage? And he’s putting his own money up front to make it? What the hell is this man thinking?

Faces would later earn three Oscar nominations and embed itself in the history of independent cinema. Though his 1974 film A Woman Under the Influence tends to be his most favored work, and his independent filmmaking ambitions dated back almost 10 years prior with 1959’s Shadows, the raw spirit of the independent film arguably begins with Cassavetes’ 1968 landmark.

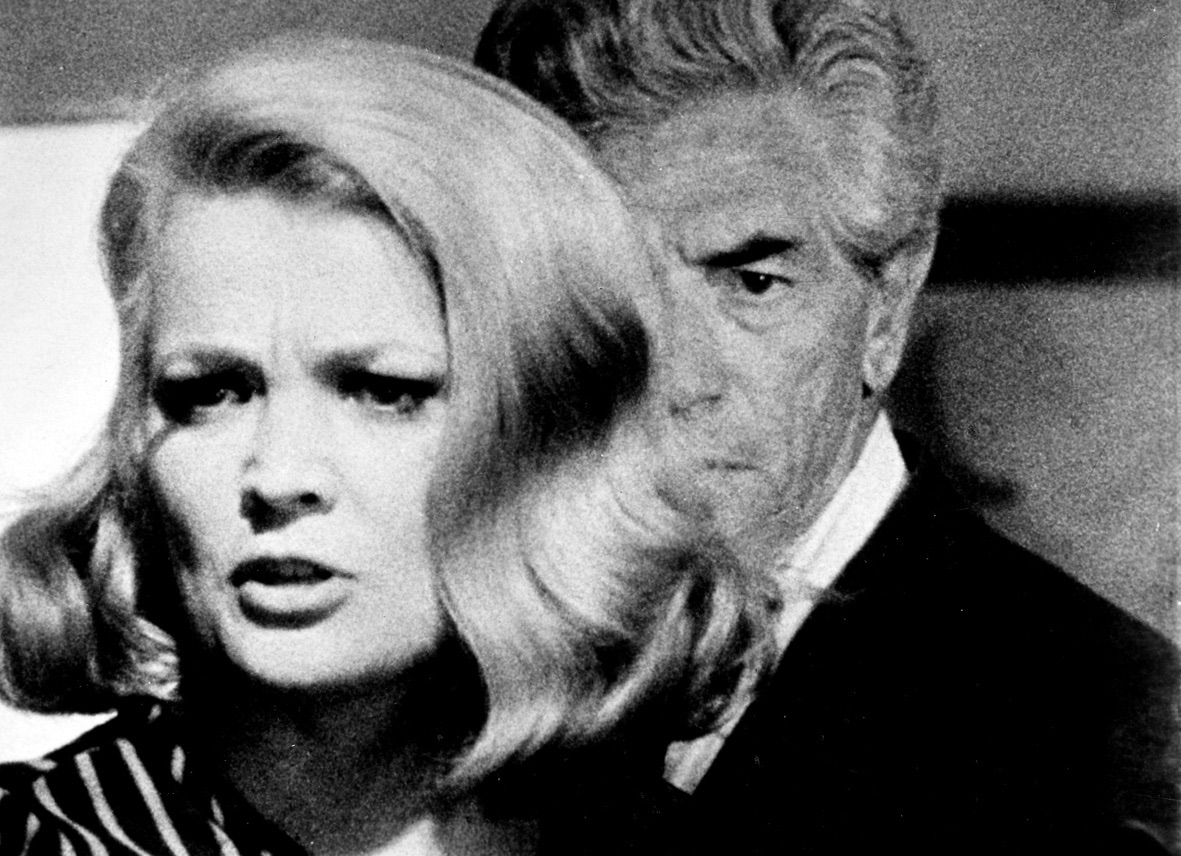

Seymour Cassel and Lynn Carlin are a middle-aged couple whose relationship is on rocky territory, and now they’ve had enough. They bitterly part ways, and over the course of the evening, they spitefully mingle with members of the opposite sex, respectively. The setup is as simple as that. What makes Faces so striking, though, is its unhinged realism: there is no melodrama to keep the audiences interested, in a conventional sense, anyway.

Scenes do not rush to the point – they observe for lengthy periods of time, letting the characters and the situation sink in. The characters are not particularly interesting. In fact, they’re quite pathetic, and these characters will be the audience’s world for the next 2-plus hours. Ironically, the film is striking beyond all reason.

2. Easy Rider (1969, dir. Dennis Hopper)

With the older generations’ disapproval of counterculture and the country’s controversial involvement in Vietnam, these proved to be frustrating times for young Americans. The escapism of cinema gave no relief either, with its melodrama, insufferably long historical epics, over-traditional good guy vs. bad guy dynamics, and other such tired conventions.

With nowhere to turn for relief or escape, it seemed like there was nobody to understand or celebrate the values and ideology these young folks held so tight to their being. Some could say they were born to be wild

Then came Dennis Hopper, rolling in on his Harley with a $400,000 budget like a cinematic messiah.

With two characters embodying counterculture – hippies and bikers – and a cross-country road trip complete with cocaine, LSD trips, free love, complete with the legendary use of Steppenwolf’s “Born to be Wild” rocking in the background, Easy Rider proved to be the ultimate cinematic refuge from the suffocating world of social norms.

The result became a worldwide cinematic phenomenon, not only ushering in a whole new era of movies, even launching the career of Jack Nicolson, but also a remind that a film can be about anyone and anything, no matter what margin they may reside in.

3. Two-Lane Blacktop (1971, dir. Monte Hellman)

The late ‘60s/early ‘70s is perhaps the most exciting time in American (independent) cinema: new cinematic territories that nobody dared tread before now being explored, but there was a peak in interest in foreign art house cinema.

It wouldn’t be long before filmmakers took the gritty rebelliousness of new American cinema and the reserved existentialism of foreign arthouse and blended them together, opening new doors for American cinema. Perhaps this was never better defined than in Monte Hellman’s cult classic Two-Lane Blacktop.

In their only screen performances, songwriter James Taylor and Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys (only known as Driver and Mechanic, respectively) star as young obstinate drag racers road tripping across the country. During their travels, they meet G.T.O. (Warren Oates), and thus begins a cross-country race to win each other’s cars.

Though the setup may lead one to think this will be a fast-paced race film with love letter to classic cars, what follows instead is a rather reserved existential examination of post-60s youth, a generation that was the polar opposite of the mild-mannered and dull generation before.

A generation that tried so hard to bring world peace in the face of the Vietnam War, but never happened. Instead of happiness and answers, there was only confused youth without direction. It is a presentation of existentialism that Antonioni would be proud of, and it is a quintessential example of the ‘70s indie film.

4. Mystery Train (1989, dir. Jim Jarmusch)

One could argue the entire filmography of Jim Jarmusch could single-handedly define independent cinema, and to choose one for this list is difficult. Though the choice here is Mystery Train, Jarmusch has made films that are debatably more fitting for this slot, namely his ’84 masterpiece Stranger Than Paradise. Nonetheless, Mystery Train not only has the classic Jarmuschian traits that continue to perpetuate through indie cinema, but it can also sit beside Sex, Lies, and Videotape that helped shape the ‘90s independent film boom.

Set over the course of one night, Mystery Train tells three different stories various folks and their escapades in the streets of downtown Memphis, involving a couple of Japanese tourists, a stranded Italian widow, and drunken liquor store burglar.

Though they never interrelate in the traditional sense, what is omniscient is Jim Jarmusch’s love for Memphis and its legendary rock scene, all told through Jim his quirky yet reserved sense of comedy, which would become a trademark of indie comedy, and with its uniquely fragmented narrative that may have had influence on Tarantino, Mystery Train is perhaps one of the unsung catalysts for a seminal era in cinema.

5. Sex, Lies, And Videotape (1989, dir. Steven Soderbergh)

Centering on a mutually unhappy suburban marriage, it sounds like a TV soap opera that might have been just a little too hot for the public. Ann, the wife is in therapy, where she expresses to her doctor that sex is overrated.

Meanwhile, her husband Graham is having an affair with his wife’s free-spirited sister. However, things get interesting with the arrival and temporary stay of John, a friend of Graham’s from college, and his videotape collection. John has an interesting fetish, where he tapes “interviews” with women and asks them sexually intimate questions. And thus begins an inquisitive drama about neurosis, marriage dysfunction and sexual insecurity.

On a meager budget of just over $1 million, here was the debut feature written and directed by a virtual nobody. Not only that, but how could a 26 year old first-timer possibly have the insight to make a film with this kind of material? The 26-year-old in question happened to be the now prolific and versatile Steven Soderbergh, whose 1989 effort paid off well, awarding him the prestigious Palme d’Or, as well as an Oscar nomination for Best Original Screenplay.

With a clever script, a unique vision, and a confident execution, perhaps it all started here, the film that inspired an entire generation of ambitious filmmakers in the early ‘90s.