5. Joseph LaShelle (The Apartment) – Best Cinematography

Billy Wilder’s entire filmography points to one particular skill without doubt – writing. Few writers have equaled Wilder’s astonishing ability to manufacture characters with everyday charm and an odd, endearing edginess that works wonders without being at all noticeable. While some of his darker fare like “Sunset Boulevard” left stronger impressions, Wilder was someone whose lighter works are just as memorable.

“The Apartment” is now widely considered an old Hollywood classic, Shirley MacLaine and Jack Lemmon are pitch-perfect in their realistic, tender portrayals and the production design neatly complements the goofy sensitivity of the film. But there’s so much more to adore in the film beyond that: Wilder’s impeccable writing, his graceful direction and Joseph LaShelle’s cinematography.

LaShelle captures the joy, the sadness and the aching vulnerability with an effortlessness and a beautifully heartfelt sense of autonomy. Autonomy from mere convention or from the Hollywood standards, one may never be able to tell, but there is an airiness present in the “The Apartment’s” cool visual style that is sorely absent in other films from the period.

This autonomy being singled out by the Academy even for a film that basically swept the Oscars – winning Best Picture, Best Director, Best Original Screenplay, Best Film Editing and Best Art Direction – is an unusual feat and one that proves that when change is for the better, as is in the confetti-filled, melancholic picturization of “The Apartment”, even the Academy must stop and listen, or more appropriately, see.

4. John Cassavetes (Faces) – Best Original Screenplay

John Cassavetes, best known today as the man who laid the foundations of the American independent film industry or as Mia Farrow’s husband in Roman Polanski’s “Rosemary’s Baby”, was responsible for nothing short of a revolution in cinema when he made some of the grittiest, most sophisticated dramas that dealt with socially relevant subjects in the most overwhelmingly philosophical ways.

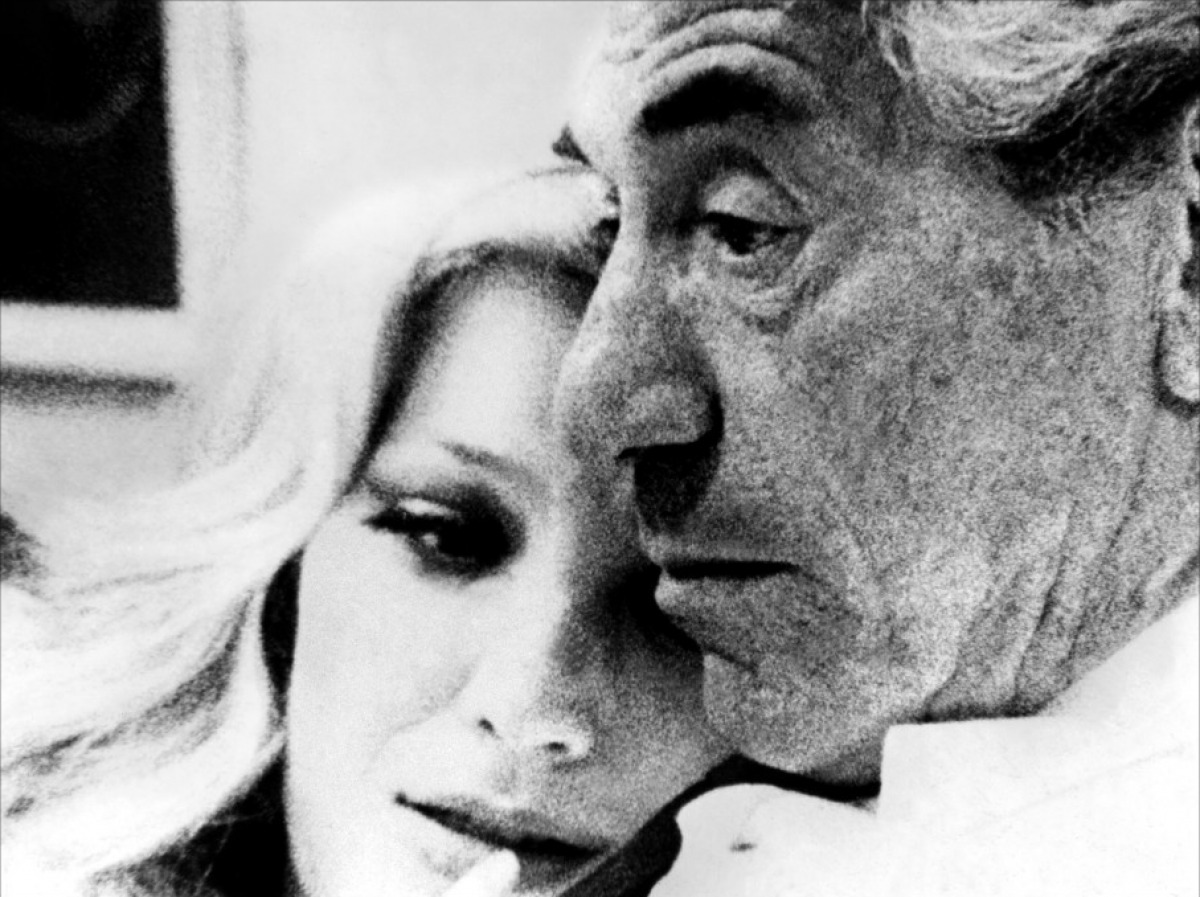

Although he was a few years away from his creative peak, which wouldn’t come until 1974’s “A Woman Under the Influence”, “Faces” represents the untarnished, raw shape that Cassavetes’s talents took in his early years. It doesn’t resolve itself neatly or offer any conclusions, but reflects a burning need to touch an element of the human experience – whether it was the sadness, the loneliness or the pointlessness – few had ever done.

Focused on a man and a woman about to end their marriage, Cassavetes’s delicately assembled film in its shimmering 16mm black and white hopes to uncover all needs unfulfilled, the perils of passing time and the crushing universality of modern life. “Faces” has no association with hope and is never in its runtime a feel-good film, but its realizations are worth contemplating and reflecting on.

The specificity of the characters Cassavetes was famous for is present here, but it fades away a little to give us the view of how helpless our situation is. Gena Rowlands is typically brilliant and the Oscar nominated performances of Seymour Cassel and Lynn Carlin couldn’t be more efficient, but it is Cassavetes’s scathing screenplay that never gives up and becomes the tallest accomplishment here.

3. Carol Kane (Hester Street) – Best Actress in a Leading Role

Carol Kane, known to contemporary audiences as the goofy, eccentric landlord Lillian Kaushtupper on the Netflix show “Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt”, to their older counterparts from her iconic, Emmy-winning role on “Taxi”, to Woody Allen fans from “Annie Hall” and to Rob Reiner fans from “The Princess Bride”, has never actually enjoyed the kind of success her talents more than calls for. Nor have those who know about her illustrious career, ever attempted to understand, let alone deconstruct the singular allure of this phenomenal actor.

But in 1975, the Academy honored Kane, then in her early 20s, for her quietly devastating turn in Joan Micklin Silver’s “Hester Street”, a sublime period piece that is largely in Yiddish and focuses on a young girl who has immigrated to America with her husband and her complicated, many-faceted life. She loses and gains almost a lifetime’s worth of treasures in the short narrative sentence of the film and Kane captures her breathtaking vulnerability and growth with such fragile selflessness, you cannot help but fall for her Gitl.

Her wide eyes fill with an unknown, ambiguous emotion whose presence alone demonstrates the depth and sincerity that lies at the beating, generous heart of Kane’s performance. Not much is ever said about Kane or this film or the fact that she is an Oscar nominee, but this small film is all the proof you need to form the opinion that there should be.

2. Reginald Mills (The Red Shoes) – Best Film Editing

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, also known as the Archers, are so elemental in developing the purity of cinema as an art form, that its thoroughly surprising to note that many self-proclaimed cinephiles remain blissfully unaware of their work or its mammoth influence. They are yet to be confronted with the sweltering, almost unnatural energy contained in each of their films, the stunning repression that rendered each frame combustible and masterfully composed.

“The Red Shoes” is widely believed to be their best film, or at least their most technically forward, and aside from the reliably brilliant writing and direction, as well as Moira Shearer’s stunning lead performance and the film’s sharply fine-tuned commentary on an artist’s obsession with perfection, the film’s costumes, score and production design get the major share of attention. But not discussed as much is Reginald Mills’s crazily modern and riveting editing.

It at times runs two steps ahead of the film, underlining the almost breathless, swooning and operatic tone and throws you into a spin and at times sits back and reflects on the haunting despondency that envelops this dark film. This double whammy landed him a well-deserved Oscar nomination and is one of the few times the Academy were brilliantly on-point.

Without this shaded, textured editing, “The Red Shoes” loses its urgency, its well-crafted visual aesthetic deflates like a balloon. It so deftly complements Powell’s and Pressburger’s camera, that it’s hard to imagine each moment landing as effectively as it does without it.

1. Ingmar Bergman (Cries and Whispers) – Best Director

Death surrounds Bergman’s deeply harrowing film as if it feeds off it. It taints the grandeur of the house the majority of the film takes place in, to an extent that it seems to be drenched in the color of blood. The crimson is so pervasive in this film, it might as well be flooding from the walls and the characters’ bodies. We don’t question it, but are instantly and constantly hypnotized by it.

Bergman had always been a gigantic force in world cinema, but with “Cries and Whispers”, everyone sat up and paid attention. What many don’t know is that even in a year as competitive as 1973, Bergman’s film got multiple Oscar nominations, including Best Picture and Best Director. Although the film is staple for cinephiles across the globe, this factoid is known to a select few, because the film is always overshadowed by “Persona”, widely considered to be Bergman’s masterpiece and perhaps rightly so.

Bergman is frequently accused of being a better playwright than a filmmaker. And his early films might suggest a more theatrical instinct, but later in his career, the inescapable sensuality of his films cannot be denied. They make an astonishing, bold use of light and color and that is best exemplified by the gloomy, devastating “Cries and Whispers”.

You immerse into the despair invading Bergman’s characters and it doesn’t let go long after the film is over. Harriet Andersson, Liv Ullmann and Ingrid Thulin eat at you and you let them, because their sadness is almost glamourous. You can sense it, smell it. Bergman famously said, “I feel that in “Persona”—and later in “Cries and Whispers”—I had gone as far as I could go. And that in these two instances when working in total freedom, I touched wordless secrets that only the cinema can discover.” It’s hard to disagree with him.

Author Bio: Anmol Titoria is a student at University and has been writing and engaging in many a parley about film since he was in school, where he was responsible for writing the film column of the monthly newsletter. He professes his love for Kubrick, Bergman and Tarkovsky in ways so multifarious and with such alarming regularity that his family has considered throwing him out repeatedly.