6. Fight Club (1999): dir. David Fincher

Without a doubt, Fincher captured the cultural zeitgeist after successfully adapting the Chuck Palahniuk novel of the same name, offering commentaries on everything from masculinity to consumerism and love.

The film follows the exploits of an unnamed insomniac narrator (Norton), who shambles through life as a zombie, a slave to consumerism and corporatism. He works a mindless job serving people he hates again and again, day after day, finding solace only through the materialistic aesthetics of his apartment.

That is until he meets Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt). Together, they start Fight Club, a sanctuary where men live out their most animalistic urges, far away from the judgement of the society that they seem so chained too.

Eventually, taking the fights out of the basement and into the streets, Tyler begins Project Mayhem: a complete reorganization of society. A reorganization through destruction. Soon enough, Project Mayhem and Fight Club becomes an international icon, and seemingly everyone is in on the game, even if it seems to be spiraling wildly out of control for the narrator.

What gave “Fight Club” the right ammunition to elevate it to the cultural status that it has achieved today is its apt critique on the modern man and his place in society. It stressed the societal role of emasculation and its subsequent pressures on men, accentuated the poisons of consumerism and materialism (arguing how this lifestyle ultimately leads to a pointless, hollow existence), as well as recapturing the feeling of life in a world where you are numbed by the sheer over-stimuli of your senses.

We are a culture increasingly becoming dependent upon Facebook, Snapchat, Instagram, YouTube, likes, dislikes, followers, and superficial online attention, as well obsessive over the current styles of materialism. Both Palahniuk and Fincher knew what they were taping into when they wrote their respective works, and Tyler Durden (the seed of both of their creations) serves as the antithesis to contemporary culture and nearly everything our capitalist society supposedly embodies.

7. Elephant (2003): dir. Gus Van Sant

Gus Van Sant’s “Elephant” traverses down the same path as “The Dirties,” in that it is also an examination on the drives of psyche and murder. It also finds its story based around the scenario of a school shooting. However, unlike Matt Johnson’s comedic and pop-culture-centric veil to lull you gently into the nightmare, Elephant plunges you into it headfirst, without warning.

A much more cerebral experience, Elephant is a very multifaceted story. Told through the scope of multiple perspectives, the camera follows several students through the typical day in the life of a high school student.

We follow the jock, the quiet girl, the photographer, and the kid with the alcoholic dad (to name a few), as they walk through classrooms, make casual conversations (often interwoven between each character, however minor) and through this tactic we, the audience, slowly start to become them. We get a sense of the school as a character in and of itself, and when the violence starts, we are thrusted into the situation, just like they are.

At the start of the violence, we are juxtapositioned by the stories of the shooters themselves. They are outcasts, the losers of the school. We follow them home weeks before the shooting and introspectively observe their lives, how they play violent video games, purchase assault rifles, map out their shooting sprees, and, more importantly, face their interpersonal confusion, both sexually and psychologically.

Much like it was for The Dirties, the social and psychological aspects of what could potentially drive people to commit mass murder, is put under discussion. However, Gus Van Sant opts to hold conversations periodically throughout the film between characters, asking such things like “how do you know if something is wrong with someone,” asking us, the viewer, whether or not the motivations to murder is innate or created.

Van Sant certainty seems to be suggesting both, but the beauty of the film is that he never tells the audience which interpretation is the correct one. As stated with The Dirties, in a post-Columbine, Sandy Hook, Virginia Tech, and San Bernardino world, it is always important to ask these types of questions and never let them stray too far from our collective consciousness.

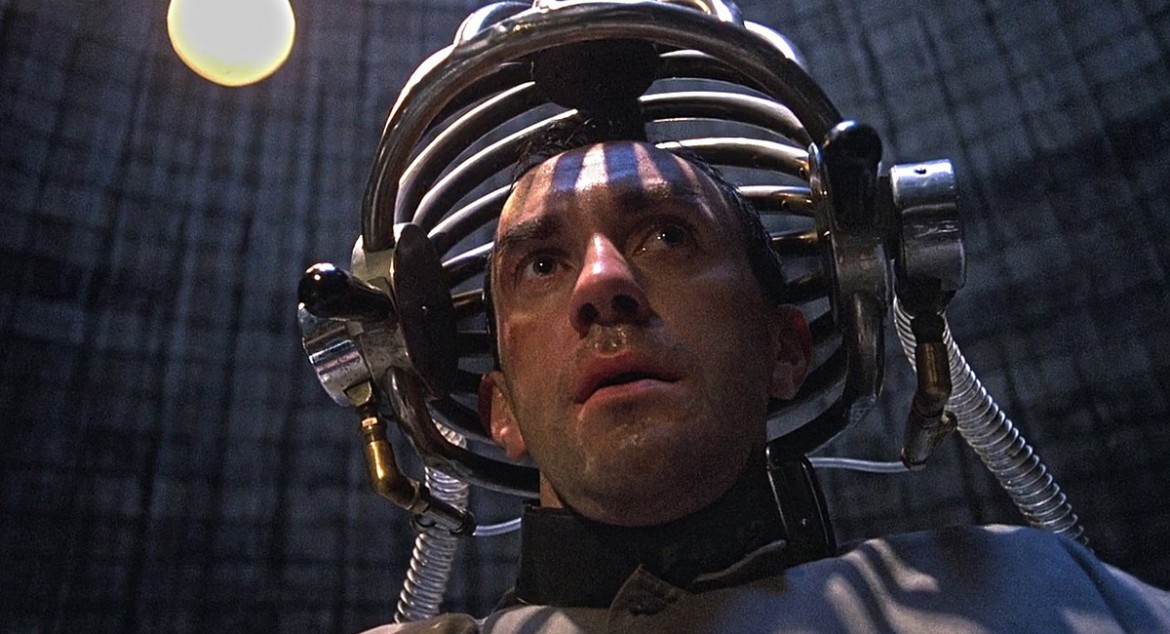

8. Brazil (1985): dir. Terry Gilliam

One of the most influential auteurs of our time, Terry Gilliam remains a key talent in the art of cinema. The only American Monty Python, his unorthodox vision of film can only be described as grandiose, unconventional, and strange. A man of remarkable talents, Gilliam sought to implement his quick witted Python-humor, mixed with his unsentimental perceptions of the world, into a new film that would ultimately serve to comment on the society with which he grew increasingly frustrated with: a world overwhelmed with bureaucracy and superficialities.

“Brazil” focuses on Sam Lowry (Johnathan Pryce), the average everyman who is just trying to live a perfectly normal existence in a consumer-driven dystopian world. He works a dead end job for the totalitarian government which rules this society (very similar to the one in George Orwell’s “1984”), taking every chance he can get to remain in the shadows of existence.

By day, he is content with the mediocracy of his life, but when he dreams he sees himself flying high over the world with visions of a woman calling his name, a robotic samurai that tries to kill him, and an overwhelming sense of oppression by the bureaucratic skyscrapers.

During a routine work-related rotation, a chance meeting unites Lowry with this woman (Kim Greist) in the real world. As a result, mystified by her presence and meaning, he sets to finally escape from his unambitious and rundown life with the additional help of characters like renowned rebel Archibald Tuttle (Robert DeNiro) and the woman herself, named Jill Layton.

What is so fascinating about “Brazil” is its emphasis of an absolute, all-encompassing bureaucratic presence within society. Every single aspect of culture requires a signature or another form in the film, even highly totalitarian acts like abduction at the hands of the government (“here is the receipt for your husband” is a direct line spoken within the film). It was in fact this very abuse of information control and obsession that Terry Gilliam found inspiration for creating this film because he was so sick and tired of the sensationalizing of technology and data in his own life.

Much like the comparison that was drawn in “I’m Still Here,” Gilliam’s film critiques society’s compulsive desire for information and makes a joke of it by exposing its ridiculousness. Again, in a world seemingly ruled by social media and the internet, this awareness of our addiction to information and bureaucracy is key to understanding ourselves as a civilization.

9. The Dark Knight (2008): dir. Christopher Nolan

The Dark Knight took the mainstream by storm following its release in 2008. Christian Bale’s return to the role of the caped crusader was a greatly anticipated homecoming to audiences and the film’s own flair for iconic Chicago vistas as well as the dark, gritty realism portrayed through Nolan’s captivating lens proved to ultimately be a fresh and invigorating experience for moviegoers everywhere.

The single greatest reason for this film’s success, however, is none other than Heath Ledger’s ghastly portrayal of Batman’s classic arch nemesis: The Joker. This guerilla and horrific (yet totally magnificent) agent of chaos enraptured audiences around the globe with his signature grunge makeup, smiling scars, ruthless demeanor, and cunning, chess-like machinations.

For his performance, Ledger won a posthumous Oscar, forever etching his name into the hallowed halls of cinematic history. Within the film, his performance captures the reality of living in a post-9/11 world of fear and terror, seemingly unable to combat the next move of those who wish us harm.

The film takes place several months after the film’s predecessor, Batman Begins. Bruce Wayne (Bale) still dutifully serves Gotham City with stoic, menacing will, now working in tandem with the Gotham City Police Department under the supervision of Jim Gordon (Gary Oldman). After the emergence of a new power player in Gotham City, newly-appointed District Attorney Harvey Dent (Aaron Eckhart), this dynamic duo decides to include Dent in this partnership.

Together, through Batman’s punches, Gordon’s legitimacy, and Dent’s cunning, they manage to jail almost every major crime syndicate in the city. The Joker takes an interest in these men and makes it his sole mission to destroy them and everything they stand for. Through confrontation after conflict, trials and tribulations, Bruce Wayne must face the full gravity of his vigilante decisions after being given the ultimate choice by the Joker, a choice which will lead to rise of the Dark Knight. No one escapes this film unscathed, especially our heroes.

The Joker’s conspiracies, maneuverings, terror tactics, and extremely unpredictable tendencies give credence to the idea that his actions are the personification of those like international actors abroad. More specifically, jihadists and global terrorists, where their desire to murder indiscriminately and destroy the common social order of society are more closely related to the Joker than we like to believe.

In the film, Gotham and everyone in it (including Batman and Gordon) are brought to their knees. After the North and South Towers fell on September 11th, 2001, the United States was a nation plunged into chaos and absolute anxiety (fears which, it is important to note, can still be felt today).

The Joker prides himself on the ability to circumnavigate conventional channels of coercion and dialect, all in the vein of disrupting the status quo. Terrorist agendas are founded on the premise of hostility through fear. Conceptual awareness of this bitter reality are key attributes to defending ourselves from this evil, and even in the film itself, Batman predicates his dogma of protection on the notion that Gotham’s citizens can rise above their fears and overcome the darkness.

The climatic conclusion to the Joker’s bomb-on-a-boat social experiment exemplifies this rationality set by Batman, in that the people on those boats make the right decision and prove they will not play into the machinations of terror. Just like the characters in the film, the United States has attempted and (in some areas) successfully overcome the prejudices and horrors of terrorism. To keep fighting against this ideology, we must rise to the occasion like Batman and learn from example, whether it be in that world or ours.

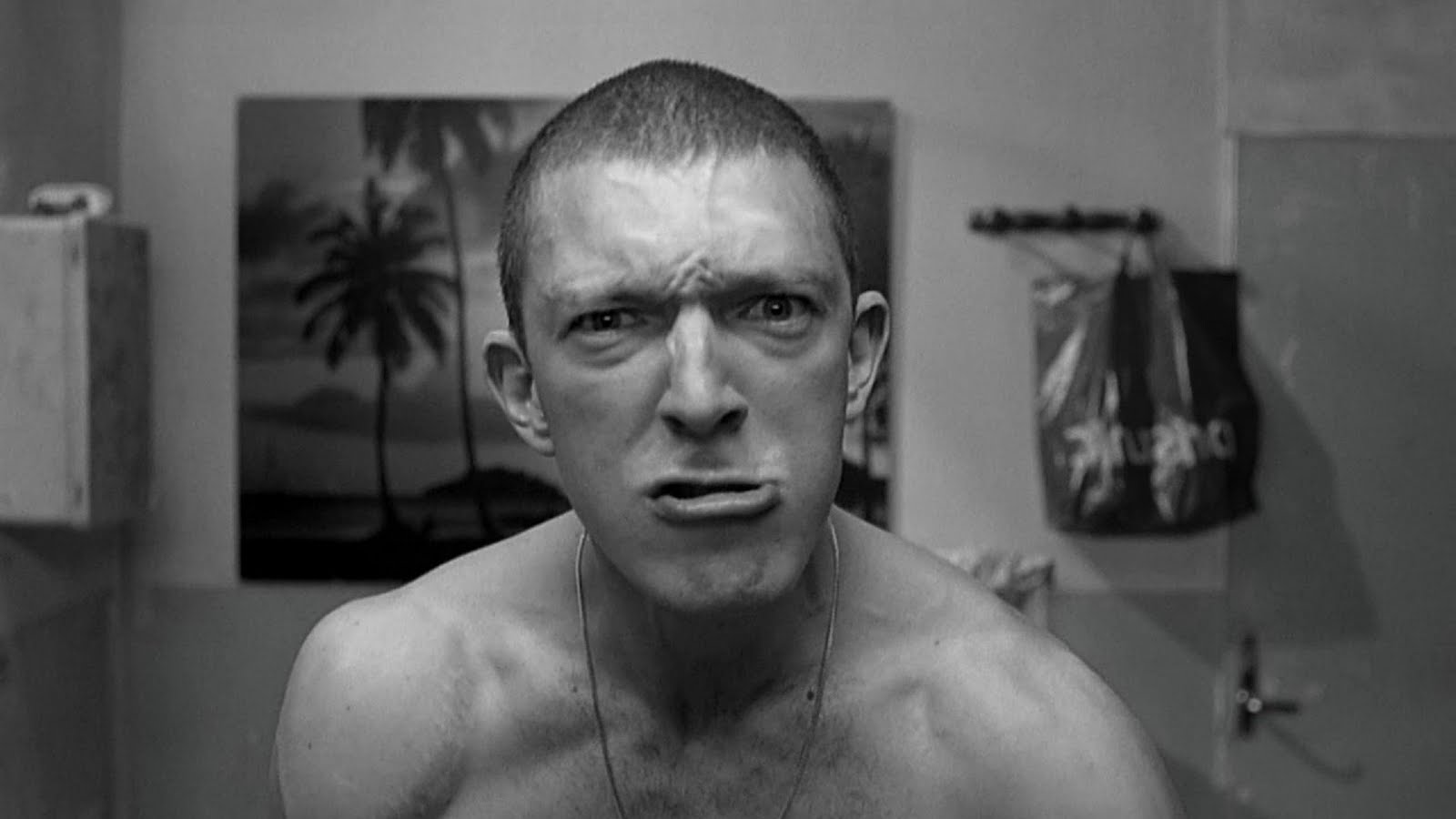

10. La Haine (1995): dir. Mathieu Kassovitz

At first, Mathieu Kassovitz’s 1995 “La Haine” may seem like a film that has passed under the cinematic radar, especially within the context of a social commentary that can be linked to the contemporary American society, but when looking much deeper into the story, striking similarities and conclusions can be drawn. This black and white French film revolves around three hoodlum youths (Vinz (Vincent Cassel), Hubert (Hubert Koundé), and Saïd (Saïd Taghmaoui)) in a housing project ghetto along the outer limits of Paris, France.

The story takes place just after a vicious riot between police authorities and the local minority population, and in the aftermath, a young Arab is arrested and beaten unconscious by the police. Our protagonists take to the streets, wandering about, interacting with friends, family, police figures, and several other interesting individuals.

All the while, as the story progresses, Vinz, the wannabe gangster of the crew, continually asserts and promises that if the young Arab dies, he will kill a police officer. When they stumble upon a lost police pistol, attitudes change and become tenser.

Notions of what constitutes the rights and wrongs regarding policing institutions is heavily scrutinized through the perspective of those marginalized individuals, some beliefs are incredibly hostile, but also some are peaceful. In fact, at the start of the film, Hubert asserts “”La haine attire la haine” (“hatred breeds hatred”) to Vinz. This will serve as the main motif of the film, up until its climatic confrontation, ultimately leaving Hubert at a crisis of faith to his own words.

Although it details the struggle of another people, in another country, in another time, the depth of struggle in Kassovitz’s masterpiece is still incredibly prevalent to that of the populace of the United States in 2017. The entire premise focuses around the constant, almost perpetual tension held between police officials and the population with which they are sworn to protect.

As it is in real life, both sides can be innocent and guilty, it’s just a matter of context and timing. There are also instances where each party is represented menacingly and innocent within the film, with both of their frustrations accurately and fairly depicted, but what ultimately comes to define their roles in society is the brutality which is afflicted upon them.

In the United States, in a post-Ferguson and Baltimore social reality (as well as the all-pervasive tension between our policing institutions and other minority groups) the struggle of combatting abuses of force remains a very relevant and controversial debate. This film attempts to tackle that conversation, humanizing each side of the spectrum, but also addressing the injustices each perpetrate.

Author Bio: Brian Gallagher is a fervent admirer of the beautiful and captivating nature of cinema. He sees it as an absolute joy to keep sharing his love of film and filmmaking to as many people as possible.