Throughout the history of film, the term “Masterpiece” gets thrown around rather frequently, loosely even, with common names like Citizen Kane and Casablanca coming to mind, being praised for their level of innovation and general greatness.

Though such films are undeniably great, there are a few black sheep (that will not be named) which are undeservingly bestowed that term, even studied in film school for their “greatness”, when they’re frankly only a step above mediocrity. Which is all the more infuriating considering how certain films that ARE masterpieces go unnoticed in favor of lesser ones.

This list aims to highlight 10 such films. Though they may not hit the same level of innovation or brilliance as the likes of Apocalypse Now or The Seventh Seal, they are undeniably great works of cinema, and more importantly, embody the very definition of the term “obscure”. Despite all of these films being either made by notable filmmakers or praised by even more notable ones, they all net less than 10000 votes on IMDB, and some even have undeservingly mixed reviews to their name.

Without further ado, these are 10 more criminally underrated movie masterpieces.

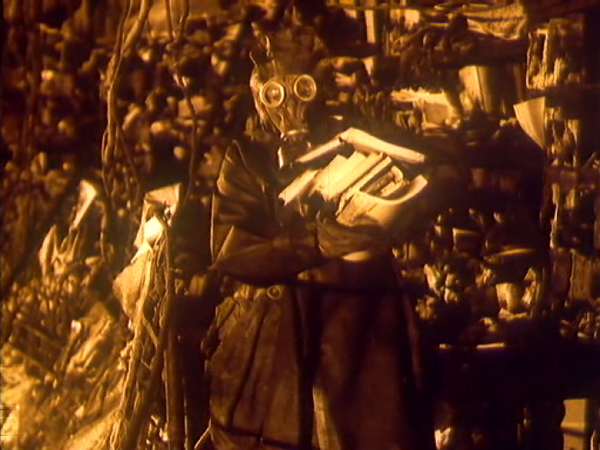

10. Element of Crime (1984)

Stylistically, The Element of Crime is far from Lars von Trier ‘s destructive handheld style. The shots in the film are visually aesthetic with so much depth to them and detail in the frame. Cuts are used sparingly as opposed to frequently. The camera meanders in an omniscient manner, with literally only a few handheld shots. Completely dissimilar to the method of filmmaking von Trier is known for today.

Nonetheless, if you were to view the film from a thematic and historic standpoint, this film is still very much the hallmark of von Trier’s filmography. The extremely creative, well executed and almost logic-defying approach to otherwise worn-out genres and the idiosyncratic way he is able to delve into the characters’ psyche is very modern day von Trier, and of course makes for an undeniably unique film, despite some inherent flaws.

As far as feature debuts go, The Element of Crime is impressive to say the least. The cinematography and set design evokes so much thought and emotion, being hauntingly beautiful in an almost Tarkovsky-esque setup, which is ironic considering the film’s hyperbolic portrayal of filth. The film sits as a landmark of von Trier’s filmography, giving the world a glimpse of what’s to follow from this Danish auteur in the years to come, as well as being one of the most unique pieces of the noir genre, giving a whole new meaning to the term “bleakness”.

9. Dead Man’s Letters (1986)

Yet another directorial debut set in a post-apocalyptic society, Soviet auteur Andrei Tarkovsky’s protege Konstantin Lopushansky’s Dead Man’s Letters manages to uniquely present an interesting story on humanity and empathy among many things, set amidst the desolate backdrop of a post-apocalyptic society.

The film follows a Professor as he hides out in a basement of a former Museum as he and a group of individuals attempt to survive the end of days. As the title suggests, the Professor spends his time (and maintains his sanity) writing letters to his son, with the content ranging from philosophical musings relating to the film’s central themes, or recountings of personal memories. The film takes a progressively desolate tone, with individuals slowly losing hope and eventually even taking their lives.

Dead Man’s Letters is perhaps the most honest films in terms of its depiction of the subgenre. In a post-apocalyptic world, how are we as a species to maintain not only our survival, but our sanity? How are we to remain hopeful in a world with none? The backdrop of the museum also serves as an integral part of the film, illustrating humanity’s desire to clutch on o our heritage, desperately holding onto the last remnants of a better yesterday.

Additionally, the lore behind the film stands out as particularly interesting. More often than not, forms of art surrounding the idea of a war-torn wasteland gloss over the events leading up to the mass-destruction, or provide some extremely simplistic and overdone backstory of alternate history with regards to heightened tensions during the Cold War.

Dead Man’s Letters instead, hinted at something more unusual – human error. Putting the film in the context of the era, the twilight years of the Soviet Union, the film serves as a cynical and melancholic allegory on the misguided ideologies adopted by the failing nation, and the state of it all should it continue its erroneous ways.

Where Stalker approaches the idea of post-apocalypse more spiritually, Dead Man’s Letters does so in a more humanitarian manner, an approach arguably more realistic and perhaps as poignant.

8. Krisha (2015)

A major issue plaguing modern American independent cinema is the fact that the films either come across as generic mumblecore-inspired “heartfelt” tales following the next hot comedian on SNL, or gimmick-filled messes that extend far beyond their own capabilities. Put simply, they either are forgettable or just plain terrible.

Krisha is one such film. The directorial debut of Trey Edward Shults, who would eventually come to make It Comes At Night two years later, a brilliant post-apocalyptic thriller, Krisha is a film guilty of both the abovementioned flaws. It’s a melodrama surrounding a recovering alcoholic returning to her seemingly idyllic family for Thanksgiving, a premise that sounds neither interesting nor inspired (with a scene towards the end coming straight out of Vinterberg’s The Celebration).

The film also features a myriad of flashy gimmicks, from fourth wall breaks, to slow-motion, long takes, aspect ratio changes and at the heart of it all, Shults is not only the director, but one of the central characters of the film. So what makes Krisha stand out despite these apparent flaws? It lives up to every single “gimmick” to the point where they come across as well executed strengths and moments of brilliance in the film.

Consider the amount of effort required to stage a long take. That level of effort is snowballed when things like location changes, length and complex blocking with multiple characters are thrown into the mix, even more so when the director himself is in front and not behind the character. This is exactly the kind of filmmaker Shults is. He’s someone that’s undeniably ambitious, but knows his capabilities and how far he can extend before people begin questioning the legitimacy of his craft.

Krisha for all its worth, is an extremely simplistic film set in a single house with a budget of $30,000 and a cast comprising mainly of the director’s family. A recipe for an amateur disaster. Even if you dislike the film, consider the production value the film has to offer, and consider these little bits of trivia, if that doesn’t get you to respect Shults and hail this film for an innovation in independent filmmaking, nothing will.

7. Chronic (2015)

An amalgam of Amour’s unyielding sense of realism and Talk to Her’s inherently unexpected storyline loosely exploring similar concepts and thoughts. Chronic offers a brilliant character study of a caring male nurse at a hospice.

The theme of empathy is explored here in an extremely unique manner, questioning the very idea of the concept. What does it truly mean to be selfless? How are we to those we are unfamiliar with? How do we convey our love? All these questions are brought up quietly through the film’s situations (The gym scene being the one that immediately comes to mind), which is remarkable considering the general lack of dialogue the film has, never explicitly inciting any philosophical discussions to explore such ideas.

Tim Roth’s portrayal of David, the protagonist is extremely layered and nuanced, very much in the vein of Javier Cámara’s Benigno in Almodovar’s Talk to Her. In the sense of how they’re able to convey the complexities and innate flaws of the characters through their expressions in scenes that would prove otherwise. Roth stands out as particularly brilliant considering his character’s outwardly benevolent persona. The character change in the film is also exceptionally well done, and on face-value, completely invisible to audiences and a powerful representation of an internal struggle.

Chronic is a film that is very distinctly inspired by the works of Michael Haneke, with Michel Franco, the filmmaker, clearly attempting to emulate Haneke’s unwavering style. However, what would generally come off as an unoriginal, uninspired rip-off ends up being a competent homage to one of the greatest filmmakers of our time as well as a great film in its own right.

6. Heaven Knows What (2014)

An exploration in the lives of inner-city white trash amidst a drug-fuelled environment. Heaven Knows What chronicles the life of one such individual, Harley, a particularly troubled one, amidst such an unsavoury environment.

The film doesn’t waste any time on superficialities, it doesn’t set up who she is, it doesn’t give her any overt goals or motivations that exist beyond the scope of drugs, and more importantly, it doesn’t glamourize anything. More often than not, films that aim to paint vices in negative light, would often tap into a small part of our subconscious, making us in one way or another, root for the characters, empathise with their sin. Not in this film.

Perhaps it’s due to the film’s inherent amateur nature, the visuals aren’t exactly anywhere near “cinematic”, but at least it doesn’t pretend to be. It doesn’t aim for any sort of profundity; it aims for gritty realism. There are literally almost no wide shots at all, every frame feels cluttered and cramped, making the film exceptionally claustrophobic.

Additionally, the sound design is also hailed as one of the film’s major strengths by many, with an absolutely haunting and incredible synth score, which is surprising especially if you consider the film’s small scale.

The film constantly stays true to its genuine portrayal of drug addiction and its boldness in its portrayal, not once did it feel like the film was made to be “good” in the traditional sense, it’s made to be honest, if anything. Which somewhat bolsters its credibility, especially with the erroneous ways of the protagonists and their nihilistic hedonist nature, it’s hard to find redeeming qualities and otherwise relate to them on a deep emotional level beyond a generic audience-character relation. Nevertheless, one has to come to appreciate intent.

The Safdie Brothers and by extension, Arielle Holmes set out to tell a story, they set out to stay true to their word, to make something that’s visceral, and the end result is probably as real of a portrayal of drug use in a film you’re going to get. It’s ugly, it’s uncomfortable, it’s messy, but more importantly, it stays true to what it is.