6. Inglourious Basterds (2009) – w., d. Quentin Tarantino

“You probably heard we ain’t in the takin’ prisoners business. We in the killin’ Nazi business.”

Quentin Tarantino, and only Quentin Tarantino, writes Quentin Tarantino dialogue. He has his own distinctive style of dialogue that has been developed and fine-tuned in all 12 of his feature length films. His dialogue is boisterous, and his characters deliver long, articulate lines with a twisted sense of humor peppered throughout. His style breaks all “the rules,” of writing dialogue, and watching a Quentin film is a great lesson in seeing a proper way to break those rules.

The first “chapter” of his fictionalized World War II epic, Inglourious Basterds, has quintessential Quentin dialogue. In this scene, Colonel Hans Landa, a Nazi known as “The Jew Hunter,” pays a visit to a French farmer, named Perrier, in Nazi Occupied France. The conversation between Landa and Perrier is long, and the pace is slow at times, but the scene never drags. The details of the conversation that seem inconsequential, such as the farm’s milk, are necessary to the intricate dialogue Quentin creates.

The structure of a scene is as important to his dialogue’s style as the language the characters speak. His scenes build tension with long conversations that often culminate in some violent act.

Most of the dialogue in this scene belongs to Hans Landa, and his character remains a scene-stealer throughout the film. He has a charisma established by his exceptional conversational skills and his witty nature. His charisma distracts the audience from his heinous profession. The tension in this scene arises from the anticipation of when this charismatic colonel will reveal his wicked Nazi nature. That moment comes when Landa brings up his nickname “The Jew Hunter.”

“Before he was assassinated, Heydrich apparently hated the moniker the good people of Prague bestowed upon him. Actually why he would hate the name “The Hangman” is baffling to me. It would appear he did everything in his power to earn it. But I, on the other hand, love my unofficial title precisely because I earned it.”

That is a brilliant Quentin line. It is long and wordy, but the dialogue is still dense and tight. It is just one of Landa’s small monologues that make up the dialogue in this scene. And this line, which foreshadows the scene’s violent culmination, where Landa’s men fire rounds of bullets into the Jewish refugees under the floorboards, reveals one of Quentin Tarantino’s most spine chilling villains. Quentin Tarantino gets away with jamming so much violence into his films by balancing it with scenes of superb dialogue.

7. The Royal Tenenbaums (2001) – d. Wes Anderson, w. Wes Anderson and Owen Wilson

“Yes, I know, you’re in love with Richie. Which is sick and gross.”

Wes Anderson and Owen Wilson’s absurdist script, structured like a novel, about Royal Tenenbaum’s attempt to reunite his grown children, has a sparse style of dialogue. Brevity is the essence of all good writing, and essential to writing dialogue in particular. A narrator reading the narration from the “book” the film mimics tells much of the film’s narrative. As a result the dialogue doesn’t carry as much responsibility in advancing the plot and establishing the characters.

One of the many bizarre conflicts in the Tenenbaum family is the love story between Richie and his adopted sister, Margot. The forbidden love shared by the two of them tortures Richie more than it does Margot. It drives him to a suicide attempt, which fails, and leaves Richie hospitalized.

After releasing himself from the hospital, Margot finds Richie reading in the tent he pitched in the Tenenbaum’s ballroom. Margot goes into the tent to talk to her brother about his suicide.

“Why’d you do it? Because of me?

“Yeah, but it’s not your fault.”

“You’re not going to do it again, are you?”

“I doubt it.”

With subtext, the writers reveal a tremendous amount about their characters. This is the first time in the film that Margot and Richie discuss their love with each other. With those lines, the writers reveal that the two characters are both aware of their shared love, and that it has not lead to any resentment between them.

The subtext underlying Margot’s line reveals that Margot feels a sense of guilt for Richie’s depression. Richie’s subtext reveals that while he doesn’t intend to attempt suicide again, he can’t say for certain that he won’t.

All of that is revealed with four short lines totaling 25 simple words. The meaning behind those lines is built with narrative elements established in the first hundred pages of the screenplay. The dialogue is a small window through which those narrative elements shine.

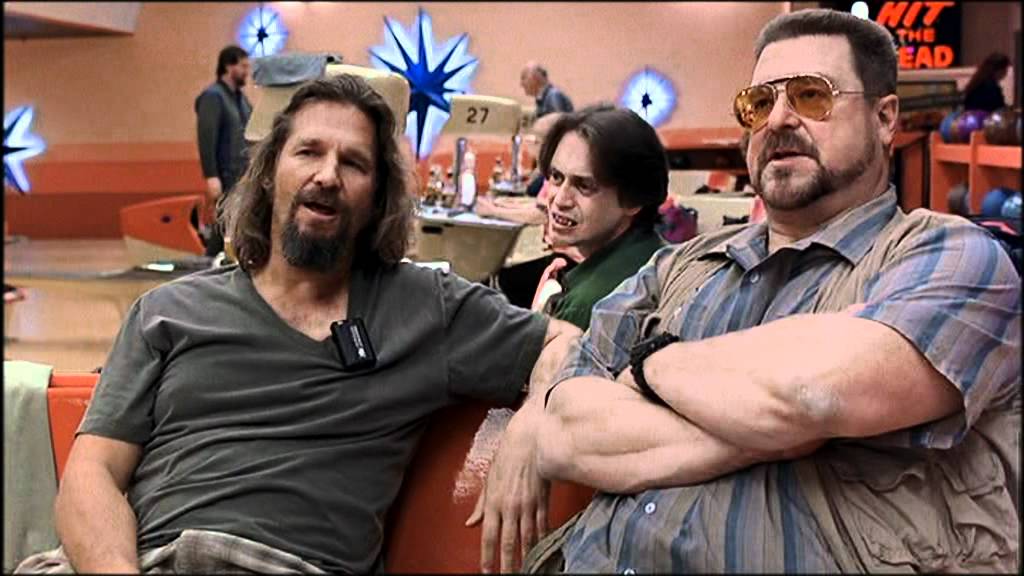

8. The Big Lebowski (1998) – d. Joel Coen, w. Ethan Coen and Joel Coen

“Young trophy wife, in the parlance of our times, she owes money all over town, including to known pornographers…”

Quotability. It’s what comedy writers strive for with their dialogue. Lines so snappy and memorable that the audience can’t stop repeating them long after the end credits have rolled. The brilliant Coen Brothers achieve that to the highest degree with their zany masterpiece, The Big Lebowski.

There are a million mind-bending ways for a writer to wrap their head around what makes a line quotable. The simple truth is, a quotable line is just good and distinctive. Of course it helps that Lebowski fans have watched the movie dozens to hundreds of times, and the dialogue (along with the rest of the sound design) is burned into their memory.

A quotable line must be delivered well, and The Big Lebowski has two gems in Jeff Bridges and John Goodman.

“Hell I can get you a toe by three o’clock this afternoon… with nail polish.” That line, delivered by John Goodman, is distinctive. He’s talking about hypothetically getting a severed toe… with nail polish. It’s quotable because it’s funny, memorable, and concise.

“Yeah well, I still jerk off manually.” That line, delivered by Jeff Bridges, achieves its quotablity in the same way. It’s simple. It’s hilarious. And there are few (if any) lines in all of cinema that resemble it.

The Coen Brothers didn’t realize that certain Big Lebowski lines would become staples in pop culture while they were writing the screenplay. They just wrote funny lines in the voices of their characters, and struck gold in casting those characters.

“Also, let’s not forget – let’s NOT forget, Dude – that keeping wildlife, an amphibious rodent, for uh, domestic, you know, within the city – that ain’t legal either.”

9. The Apartment (1960) – d. Billy Wilder, w. Billy Wilder and I.A.L. Diamond

“I guess that’s the way it crumbles, cookie-wise.”

All aspiring screenwriters should study Billy Wilder. He is one of the most prominent writer-directors of Hollywood’s golden age. Billy once stated that he is first and foremost a writer. He only became a director to ensure his scripts would be interpreted in his vision on the screen.

His film, The Apartment, centers on Bud Baxter, an insurance worker who begrudgingly lends his Upper West Side apartment to the executives at his office for their affairs. By depicting adultery and promiscuous sex, Billy was dealing with some taboo subject matter in 1960. This romantic comedy turns into a love triangle in which Bud falls in love with Fran Kubelik, an elevator operator at the insurance company, who happens to be the mistress of his boss, Mr. Sheldrake.

The film’s final scene is a stunning example of the power of subtext, and the concept of “less is more,” in writing dialogue. The scene takes place on New Years Eve, after Fran realizes that she’d rather be with Bud than be the second rate love interest of a big time executive.

Fran runs from her New Years party to Baxter’s apartment. Fran professes her love for Baxter without ever stating it. Her profession of love lies in the subtext. After Bud asks her about her relationship with Mr. Sheldrake, she replies with, “I’m going to send him a fruitcake every Christmas.”

This line is set up earlier in the film, when Bud tells Fran about a girl he once loved, who he has since gotten over, and hasn’t spoken with in years, but still sends him a fruitcake every Christmas. She never says it explicitly, but with that line she’s telling Bud that she is over Mr. Sheldrake. And she does so with a sense of wit. The writers convey that meaning with a simple line about a fruitcake.

Even after Bud tells her he loves her, Fran doesn’t respond. She just says “shut up and deal,” with a smile on her face, and keeps playing the game of gin the two of them started earlier in the film. She doesn’t have to say it with dialogue, but the context of the scene indicates that she shares Baxter’s feelings. Sometimes, in writing dialogue, certain things are better left unsaid.

10. Manchester by the Sea (2016) – w., d. Kenneth Lonergan

“I can’t beat it.”

Kenneth Lonergan’s family drama, Manchester by the Sea, achieves a certain level of realism. Apart from the film’s realist form, its realism arises from subject matter and the stark depiction of the characters’ grief.

Lee Chandler, the protagonist, returns to his hometown, Manchester, Massachusetts, for his brother’s funeral. While he’s home, Lee is haunted by his traumatic past, in which his three children died in a house fire, that he accidently caused. On top of the emotional realism the characters portray, Lonergan’s dialogue bears a striking resemblance to spoken conversation.

There is a paradoxical tight rope that screenwriters have to walk when writing dialogue. Dialogue must sound like authentic conversation, but film dialogue sounds nothing like a conversation that would occur in real life. Real life conversations are vapid to read. They are long, and the language is indirect. Screenwriters must imitate the authenticity of spoken language, and construct it in a concise way that advances plot and establishes character.

A method Lonergan uses to achieve realism with dialogue is having characters speak at the same time. A real conversation doesn’t adhere to the organized back and forth between characters as it does in film dialogue. When emotions run high people speak over and interrupt each other.

This dialogue tactic is used when Lee gets in a bar fight with two white-collar yuppies. When Lee asks why they were looking at him, one responds with “sir, we really weren’t looking at you–“ and at the same time, the other responds with “Hey! Take a fuckin’ walk — Hey — Paul — No — Don’t apologize to this asshole.” Just as it does in usual pre-fight banter, the structures of language and conversation break down, and the two white-collar professionals speak over one and other.

That artistic decision wasn’t decided on set. It was decided when Lonergan wrote the script. When two characters speak at the same time, both lines of dialogue appear side by side on the page. If one were to read Manchester by the Sea’s screenplay, they would find dialogue structured side by side throughout the whole script.

Author Bio: Logan is a writer from western Connecticut. He’s on a quest to use movies to unveil truths about the human condition. When his quest is on hold he can be found writing his novel or dancing at a Phish concert.