5. Nocturnal Animals (Tom Ford, 2016)

The second film by Tom Ford, after his debut with “A Single Man” in 2009, is one of the most fascinating movies of 2016. It tells the story of an unsatisfied art manager (Amy Adams) who receives the manuscript of a novel by her ex-husband (Jake Gyllenhaal); the novel, about a man seeking revenge for the assassination of his wife and daughter, strangely mirrors the former couple’s dissatisfaction.

As the woman keeps reading the book, the phantoms of the past come back to her mind, while her obsession with the story told begins to haunt her daily life. The two appear to look for each other through the book’s pages, trying to make peace with themselves and their mistakes.

The two stories proceed in parallel, so that the film manages to provide both an introspective psychological drama and a compelling thriller plot, to the point where the viewer easily suspends his disbelief and forgets that the revenge tale is, namely, purely fictional. Ford deals perfectly with the alternate storylines, always subverting the audience’s expectations and playing with its wish to see what the director conceals.

The two stories are represented with different visual styles, one refined and aseptic, the other harsh and crude. Served by astounding performances by the main actors – including Michael Shannon at his best – “Nocturnal Animals” owns a visceral, nightmarish quality that transcends its narrative mechanism and projects the film on a superior level of fascination.

4. The Immortal Story (Orson Welles, 1968)

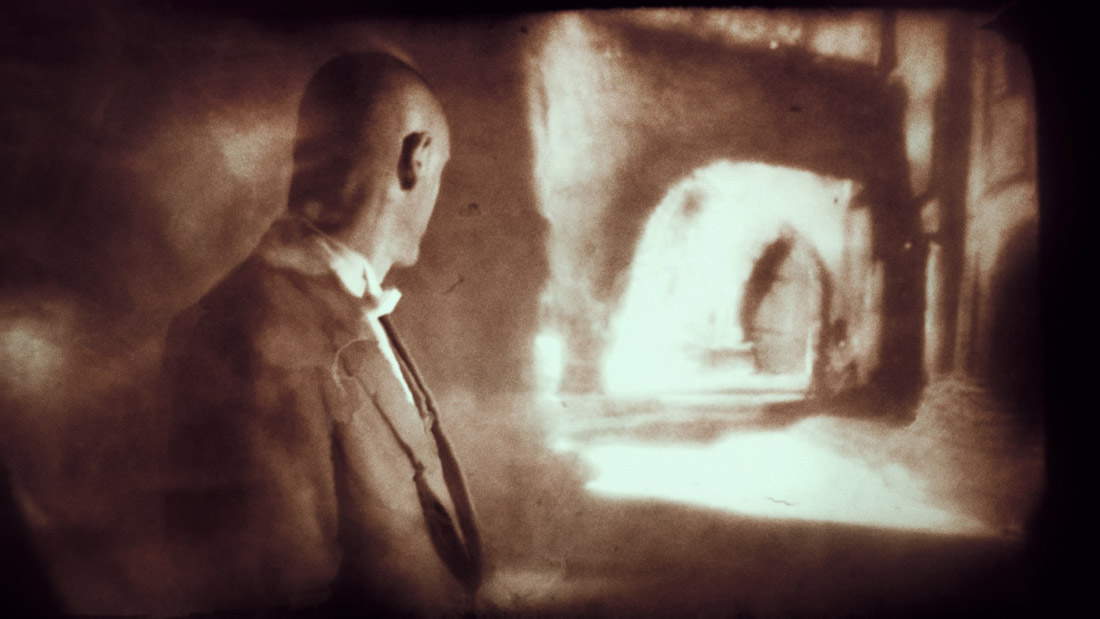

Orson Welles’ first color film is based on a short story by Karen Blixen, in which the rich Charles Clay (Orson Welles), living in Macau, hears a tale by his bookkeeper (Roger Coggio) about a rich man who hires a sailor to bed his wife and give him an heir. Clay cannot believe this story, and the only way he can is by reenacting it, by making it real in order to reaffirm his control over reality.

Clay hires a woman (Jeanne Moreau) and a sailor (Norman Eshley) to impersonate the characters of the tale, and from that point, the implications of reality and fiction are no more distinguishable, with the sailor’s tale taking over reality and threatening Clay’s supremacy.

What is most remarkable about “The Immortal Story” is that its mechanisms of a story within a story is entirely set into one narrative context, with the sailor’s tale being just evoked at the beginning and then practically reenacted. As a consequence, the whole story is marked by an aura of ambiguity, which raises the question whether what we see may be just a representation, a fiction which regenerates itself over and over again.

The film’s style shows itself as both rigorous and hallucinatory, so that it perfectly expresses the director’s effort of walking on the thin line between reality and invention. It is not surprising, therefore, to see the mastermind’s role being played once again by Welles himself, standing as the epitome of the supreme forger, just a few years before analyzing the genius of forgery in his masterpiece “F for Fake” (1973).

3. Last Year at Marienbad (Alain Resnais, 1961)

Written by novelist and director Alain Robbe-Grillet, the second film by Alain Resnais is an intriguing exercise on memory, appearance, and sexuality.

The film is about a man (Giorgio Albertazzi) and a woman (Delphine Seyrig) who meet each other in a lugubrious mansion in France. The man assures the woman that they had met one year before in that same place, so that the woman is gradually persuaded and tries to recall their previous encounter, the memory of which is different each time, providing a series of reconstructions of events that may have never occurred; the past is re-written and reenacted multiple themes with no possible solution.

In some points, the story is seen through the eyes of another man (Sacha Pitoeff), who seems to know something the characters do not know and acts as a sort of demiurge. In the end, the characters are entangled in the thick ramifications of possible pasts, unable to recall what really happened, whether they really met and fell in love with each other.

Complex, disturbing, and intricate, “Last Year at Marienbad” is also a brilliant lesson in multiple, shape-shifting narratives.

2. Inland Empire (David Lynch, 2006)

An actress in Hollywood (Laura Dern) obtains a part for a new film; as soon as production begins, the woman starts hallucinating reality according to her troubled marriage and past, while the story of the film she is working on increasingly appears to resemble her personal vicissitudes.

Moreover, she finds out that the film is a remake of an unfinished Polish movie, the actors of which died mysteriously during production. For the actress, this is just the beginning of a slow descent into madness, in which her sense of reality is threatened by the urgency of something terrible that happened to someone – maybe to her – a long time before.

After the acclaimed “Mulholland Drive”, director David Lynch took a step further into dreams and obsession, once again taking Hollywood as the setting for a tale of fame, ghosts, and nightmares. After a rather intelligible first act, “Inland Empire” slowly starts merging several narrative plans, each set in a sort of parallel dimension accessible through details (a window, a cigarette burn through clothes, a vinyl disc).

Each scene evokes a new story, a new dimension linked to the other ones by means of allusions: a conversation between two homeless women, a night party, and a nightmarish dimension inhabited by sentient rabbits (an extract from Lynch’s “Rabbits” series) are just a few of the pieces in which the story is fragmented. Beyond storytelling, beyond representation, the last feature film by David Lynch is justly established as a point of no return for filmmaking.

1. The Forbidden Room (Guy Maddin, Evan Johnson, 2015)

With “The Forbidden Room”, Canadian director Guy Maddin marks a new goal in storytelling and film structure. Inspired by hundreds of plots from lost silent films, the movie is an incredibly well-crafted exploration of the unconscious and film history, driven by the pure joy of freeform narrative.

The beginning looks like a mere pretext, with an old man giving instructions to the viewer on how to take a bath, which quickly evolves into the story of some sailors trapped in their submarine. From that point, the film proceeds to juxtapose a long series of tales, some of them told by characters in other stories, and so on. At some point, the parallel plots start to mingle with other ones in complex, unpredictable ways, so that it becomes almost impossible to figure out the structure of the comprehensive plot.

The stories are of the most diverse nature: a woodcutter looking for his woman, a girl lost on a tropical island, an old man undergoing surgery for curing his obsession with buttocks, a child meeting the ghost of his degenerate father, a man persecuted by the figure of the god Janus.

These and many other stories intermingle throughout the entire film, ranging from horror to musical to grotesque. As a glorious celebration of the silent era, “The Forbidden Room” is also a genial exploration of human psyche, as well as a wildly entertaining film.

Author Bio: Fabio Cassano is a PhD student working in Bari, Italy. He does research in avant-garde film and theater. He is also a filmmaker and playwright.