6. Walter has PTSD, and The Coen Brothers make it hilarious

Throughout the film, Walter makes irrational connections between The Vietnam War and his everyday life. During any situation in which Walter is enraged he claims his “…buddies didn’t die facedown in the muck…” for what ever enraged him to happen.

Whether it’s arguing his right to say “fuck” in public, ranting about the false kidnapping mystery he and The Dude are caught up in, or making a speech before scattering his friend’s remains, he brings up Vietnam. “I don’t see any connection to Vietnam, Walter.” “Well, there isn’t a literal connection, Dude.” His fixation on The Vietnam War, particularly his experience in it, is a result of the posttraumatic stress disorder he developed while serving overseas.

PTSD is a tragic condition in almost any context, but somehow the Coen Brothers manage to depict it in an uproariously funny way. Walter’s outbursts of rage are some the most gut-busting scenes in the movie. The most notable is when Smokey, an opposing member of their bowling league, steps over the line on one of his rolls.

Walter tells Smokey to mark the roll “zero,” because of the violation, and when Smokey protests Walter responds with “Smokey, this isn’t ‘Nam. There are rules.” When Smokey continues to refuse, Walter erupts in anger and pulls out a gun on Smokey. All the while he’s yelling “…AM I THE ONLY ONE WHO GIVES A SHIT ABOUT THE RULES!?”

It is not a coincidence that this irrational overreaction occurs right after Walter Mentions Vietnam. Vietnam dominates Walter’s subconscious, and aggression is engrained into psyche. The Coen Brothers are experts at squeezing humor out of dark topics, such as PTSD.

7. The Dude just wanted his rug back

The source of The Dude’s aggression, his rug, provides a comic irony The Coen Brothers often explore. Something as simple as a rug is the catalyst for this dizzyingly complex story. The rug causes The Dude to get drugged by a “known pornographer,” get involved in a phony kidnapping scandal, and get threatened with castration.

The replacement rug that The Dude steals from The Other Lebowski is what leads him to his “lady friend,” (The Dude’s sentiment for a romantic relationship) Maude Lebowski (Julianne Moore), The Other Lebowski’s daughter.

The rug The Dude steals has a sentimental value to Maude, which causes her to then steal the rug back from The Dude. Maude sheds a light on the perplexing plot that clarifies The Dude’s perspective on The Other Lebowski’s motive in the story. The light she shed is what leads The Dude to solve the entire mystery.

The seemingly miniscule narrative device of the desecrated rug gets The Dude involved in a massive conflict, and his replacement rug, that connects him to Maude, is the key to resolving that conflict. It is characteristic of The Coen Brothers to pack dense meaning into each of their narrative devices, even if it is as small as a rug.

8. Nihilism is the worst ethos

The Big Lebowski is brimming with a variety of philosophies and ethoses, which are practiced and expressed by many characters. Certain characters, such as Walter or The Other Lebowski, constantly draw attention to, and comment on beliefs that are different than their own.

Certain ethoses are portrayed more positively than others, but nihilism is unmistakably portrayed as the most despicable of all beliefs. “Say what you want about the tenets of National Socialism, Dude, at least it’s an ethos.” This is Walter’s sentiment when he first learns about the nihilists. This proud United States veteran is claiming that even Nazism is a better alternative to nihilism.

When nihilism is mentioned for the first time in the film, The Dude nonchalantly replies with “oh, that must be exhausting.” The Dude may have an apathetic approach to most of the situations in his life but he is not a nihilist. At the very least, he cares about his bowling team. Bowling is trivial activity to most, but its triviality is why The Coen Brothers chose it as their protagonist’s greatest passion. Even caring about something as small as bowling prevents one from being a nihilist.

The German nihilists are the most pathetic characters in the film. They demand a ransom for a missing person that they did not even kidnap. They cut off their girlfriend’s toe to intimidate The Other Lebowski. They break into The Dude’s home and threaten to “cut off his Johnson.”

And in the end, after it is learned that Bunny was never kidnapped in the first place, they still demand their ransom, which makes them look like a bunch of fools. The fight with the nihilists is what leads to the death of The Dude and Walter’s best friend and bowling teammate, Donny (Steve Buscemi). They are nothing but incompetent morons throughout the entire film.

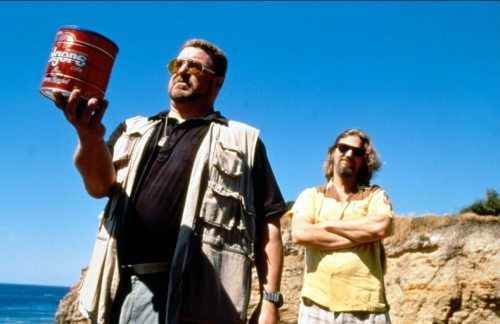

Donny’s death further proves that The Dude is in fact not a nihilist. A true nihilist wouldn’t grieve over someone’s death. The Dude is devastated when he and Walter scatter Donny’s ashes. And in their grief, the only suggestion Walter has to cheer them up is to go bowling.

Between the convolution that arises from the multitude of ethoses at play and the apathy of the protagonist, it is easy to misinterpret The Big Lebowski as a nihilist film. But a deeper examination proves that, through bowling, The Dude’s altruism, and the negative portrayal of the nihilists, it is an anti-nihilist film. The Coen Brothers are telling their audience that amidst the madness and confusion in life, it is necessary to believe in something.

9. Castration Anxiety

During the scene where the audience learns about the ransom note, The Other Lebowski asks the dude, “What makes a man, Mr. Lebowski? Is it being prepared to do the right thing, whatever the cost?” The Dude responds with “That and a pair of testicles.”

Even though it is primarily portrayed in The Dudes, he cares, deeply, about keeping his penis. His castration anxiety is among the most significant aspects of The Dude’s character.

If there is a theme song of the film, it is “The Man in Me” by Bob Dylan. It plays twice in the film during moments where the audience gets insights on The Dude’s manhood.

The first time it plays is over the opening credits, during which the audience sees gorgeous shots of people bowling in The Dude’s regular bowling alley. Bowling is The Dude’s greatest purpose in life. A purpose (or profession) is a primary characteristic of being a man in modern society. Considering that, bowling is an important element of “the man in” The Dude.

The second time “The Man in Me” plays is the moment after The Dude sees Maude for the first time. It plays during a dream sequence in which The Dude is flying over Los Angeles, Chasing after Maude, who is flying on the rug she just reclaimed from The Dude. The purpose of a penis (the thing The Dude claims is what makes someone a man) is to reproduce. Maude is the woman with whom The Dude reproduces.

It is not a coincidence that “The Man in Me” only plays during these scenes. The relationship between the song and the images it plays over creates the meaning that bowling and his “lady friend,” Maude, are what make The Dude a man.

Another song that plays over one of The Dude’s dream sequences gives the audience insight into his castration anxiety. It is “Just Dropped In” by Kenny Rogers and The First Edition.

The dream starts with two bowling balls and a bowling pin forming the shape of a penis (again, bowling is equated with The Dude’s manhood). The sequence then goes to a trippy bowling alley in a grand black void. Maude, dressed as some kind of Viking/bowling queen, is the focus of the dream. Maude and bowling, the two focuses of the scenes in which “The Man in Me” plays, are also the focus of the dream sequence which also features a song referring to The Dude’s Manhood.

With the chorus of “Just Dropped in” singing “I just dropped in to see what condition my condition was in,” the Coen Brothers are inferring that The Dude, and the audience, is dropping in to The Dude’s subconscious to see what condition his condition was in, castration anxiety being his condition.

Maude and bowling represent the Dude’s manhood in the dream, just as they do during the sequences featuring “The Man In Me.” Castration anxiety manifests itself when Maude and the bowling alley disappear and The Dude is running through the black void while the nihilists chase after him snipping a giant pair of scissors.

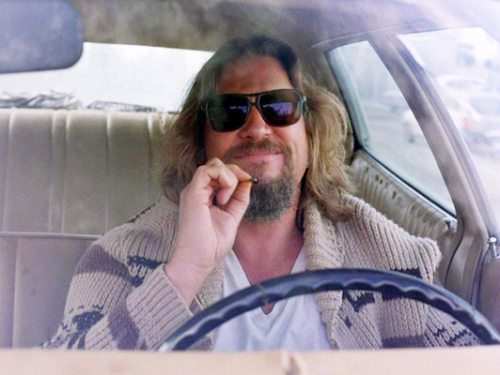

Castration anxiety is represented in The Dude’s conscious actions, as well as his subconscious. There are two specific scenes where The Dude reacts to a dangerous object falling onto his lap (right next to his penis). One is when the nihilists break into his home and drop their ferret into his bathtub, and the other is when he drops a lit joint onto his lap while driving his car.

In both scenes he has a reaction of sheer terror, much like when the nihilists chase him with scissors in his dream. He shrieks and kicks and flails when the threats near his penis. These instances are even more distinct considering The Dudes mellow nature. Those are his most “undude” moments.

Taboo and complex subject matter, such as castration anxiety, is characteristic of a Coen Brother film. It is a topic with a twisted darkness that invokes a certain sense of humor. The Coens’ brand of comedy is dark and absurd, and a theme of castration anxiety fits that description. It is also of their paradoxical narrative tendencies to use The Dude, a character that is far from the traditional image of masculinity in America, to represent the one thing that definitively makes a man: having a penis.

10. The Dude Abides

There is one explicit and absolute truth that a viewer can conclude from The Big Lebowski: “The Dude abides.” That is the last line The Dude says in the film, and that brief statement is the most comprehensive articulation of The Dude’s existence. He’s just cruising along in life, going with the flow, accepting life as it comes, and “takin’ her easy for all us sinners,” as The Stranger would put it.

His peaceful acceptance of the chaos in his life and the ease at which he does so makes The Dude a representation of an Americanized Taoist. His life of bowling, doobies, and White Russians is a life of simplicity, which is necessary in a Taoist life. The Eastern ideals that The Dude practices are at the heart of the film’s ideological level of meaning.

The Coen Brothers use The Dude’s story to state that throughout the madness, convolution, fear, anxiety, and turmoil that is inevitable in life, and amidst the bombardment of philosophies that are designed to guide one through those trials, the best approach is to say “fuck it, man” and not let those things bother you. Just “take it easy, man” and abide.

This simple, liberating, and beautiful message that The Coen Brothers create with The Big Lebowski is the primary cause of the film’s deep resonation with its audience. No Coen Brother film has a more devout fan base than The Big Lebowski. There are conventions for the film. The plethora of hilarious and insightful quotes snuck their way into the canon of American pop culture because the fans recite them and live by them as if the film is a philosophical text in its own right.

There is even a subculture of fans that have developed a philosophy based on the ideals the film exudes. It is known as Dudeism. It may be considered a “mock religion” by most, but the fact remains that The Coen Brothers made a film with an ideology so dense, so truthful, and so impactful that hundreds of thousands of people use it as the primary text from which they draw meaning and gain clarity of their lives.

The Coens have made several films with tremendously mesmerizing narratives. Declaring one of them as their best is near impossible. Films are subjective artifacts with immeasurable elements. There is no quantifiable data that can be used to compare the narrative and ideologies of any film side by side.

However, considering the impact of The Big Lebowski on its audience, and the sophistication of which The Coen Brothers create its complex narrative elements, and multifaceted themes, it is their greatest cinematic achievement. Comprehending its themes and the intricacies of its narratives demands multiple viewings, and the film is a delightfully intoxicating potion that its audience can’t stop drinking.

Author Bio: Logan is a writer from western Connecticut. He’s on a quest to use movies to unveil truths about the human condition. When his quest is on hold he can be found writing his novel or dancing at a Phish concert.