The word ‘masterpiece’ is often hyperbolically overused in the world of art, and even in cinema. It should not be used lightly, especially considering the large amount of high quality films that emerge from contemporary (post World War II) cinema. Differentiating ‘masterpieces’ from the lower tiers of film quality can be difficult, with art being subjective and often opinion based.

However, 1973’s “The Holy Mountain”, a film with no initial widespread release, mainstream appeal, or even comprehensible plotline, simply must be deemed a contemporary cinematic masterpiece of our times. A feature with overwhelmingly intense imagery for the entirety of the work, it blends the avant-garde world of violent surrealist Alejandro Jodorowsky with a mystical depiction of the Western society of the early 70s, a period where psychedelia, religion and the post-hippie feeling was rife.

Further so, “The Holy Mountain” is one of the great ‘cult’ films of all time, coming up against the odds from little financing and release to become a work with huge acclaim and devotion from audiences across the world. Its vast influence on popular culture must also be taken into account, with a legacy as one of the first cult films ever, as well as a hardcore reputation as one of the most disturbing and shocking films moviegoers will ever see.

Jodorowsky himself was almost as interesting as the feature; an eccentric intellectual with a passion for mystical exploration and LSD, his aesthetic finesse in directing has resulted in one of the most visually dynamic films ever made, which also offers religious and societal representations throughout.

It may not be the most obvious choice for a cinematic ‘masterpiece’; however, from the point of view of surrealist and cult filmmaking, Jodorowsky’s “The Holy Mountain” is undoubtedly a genius work of filmic art, and the 10 reasons below explore why it is one of the few contemporary surrealistic masterpieces in the whole of cinema.

1. A Mystical Exploration of Western Society

Being a ‘fantasy’ film, mystical facets and occurrences are almost expected to be involved, and Jodorowsky does not disappoint. The motif of tarot cards is present throughout, with the central character, The Thief, being represented by the Fool card, which often symbolises a protagonist who contains several of the main human archetypes such as greed, helplessness and friendship.

This is just one of the symbolic devices Jodorowsky uses to represent Western esotericism in “The Holy Mountain”, and through these tarot cards, he also implies the fate of the characters and their implication on the film. For example, the Thief’s friend, an armless, legless dwarf, is represented by the Five of Swords card, which implies defeat, pre-empting the end of the film where the protagonist must spiritually rid himself of this dwarf in order to progress onward toward immortality.

Further than this cinematic symbolism through mystical plot devices such as tarot cards, Jodorowsky explores Western society and facets of it throughout the work. A key line of dialogue – “You can turn yourself into gold” – can be seen as a clear reference to the system of capitalism we have in place, a society in which, if you work hard enough, you can achieve anything.

On the opposing hand, the burning of money and high focus on spirituality suggests that financial success is not the purpose of our existence, but rather to explore ourselves and “turn ourselves into gold” mentally. This message can be interpreted as both a criticism and piece of advice to Western society; however, there is no doubt that throughout “The Holy Mountain”, through all of the surrealism and visual appeal, Jodorowsky creates a pertinent message about our society’s attitude toward life and spirituality, and how we should attempt to approach it differently.

2. Filmed on only $750,000

Money in the film industry is, and always will be, a large factor in a movie’s completion and success. Production companies often control the direction of a film in both its narrative and creativity, especially so in the world of Western cinema and Hollywood. It is amazing then that, on the relatively low budget of $750,000, “The Holy Mountain” was shot with such precise execution.

With constant vivid surrealism throughout, it would be assumed that these fantastical set pieces would cost a bomb, being filmed in 1972 Mexico. Furthermore, it is impressive that Jodorowsky’s creative impulses were clearly not restrained whatsoever, with Allen Klein (the Beatles’ manager at the time) seemingly handing complete control to the unbridled imagination of the Mexican filmmaker.

Both John Lennon and George Harrison were impressed with Jodorowsky’s previous effort, “El Topo” (1970), leading to Lennon and his infamous wife Yoko Ono contributing toward the funding of his next feature through Klein, along with Roberto Viskin and Jodorowsky himself. Regardless of who produced the film, or even why they did, the fact that a film as consistently visually stimulating as “The Holy Mountain” (with a large cast and several bizarre sets) was filmed with such a subjectively poor budget is a testament to the skill of the crew involved, as well as the quality of the final product itself.

3. Gained Popular Cult Status Despite Limited Theatrical Release

As mentioned above, the budget for “The Holy Mountain” was relatively low in comparison with mainstream cinema at the time. However, the financing for the film seems vast when juxtaposed with the film’s box office returns – only around $95,000 was made from the film, and this was with a re-issue.

Despite having its premiere at the 1973 Cannes Film Festival, Jodorowsky’s magnum opus was not initially given wide release, leading to it being shown consistently on Friday and Saturday midnights at New York City’s Waverly Theatre, and eventually aiding it in becoming one of the most popular and controversial ‘cult’ following films of all time. Often, it was shown with Jodorowsky’s previous and similar work “El Topo”, again elevating the film to level of cult dedication, as well as allowing it to have a strong influence on popular culture, especially in the world of surrealism and Mexican cinema.

More than 30 years after its initial release in 1973, “The Holy Mountain” was finally given a restored print re-release (paired with “El Topo”) in 2007, showing just how popular the film has become by garnering a re-release three decades after its premiere – a feat which many films fail to achieve even with large theatrical releases. This then presents not only the quality of the film itself, but also the enthusiasm and devotion of the underground cult followers, who managed to transform a small-earning avant-garde fantasy film into one of the most revered and acclaimed surrealist features of all time.

4. The Pinnacle and Final Film of the “Panic Movement”

The Panic Movement – despite being a lesser known cinematic development – can be seen at the core of Jodorowsky’s most critically acclaimed works, and the 1973 piece “The Holy Mountain” is regarded as both the pinnacle and final film of this short but shocking collective.

Formed by Jodorowsky, Spanish director Fernando Arrabal and French writer Roland Topor in Paris, from 1962 until 1973 they horrified and awed audiences with their chaotic performances and artistic facets. Decidedly violent, surrealist and avant-garde, they sought to remove surrealism from the eyes of the mainstream and back into the experimental scene that it once spawned from in the “Surrealist Golden Age” during the 1920s and 30s.

In addition to this more societal aim, in terms of their art they attempted to “release destructive energies in search of peace and beauty” according to Arrabal, with the violence involved in several of the movement’s works seemingly working toward this final goal. With influence from the father of cinematic surrealism Luis Bunuel, as well as the Greek God of the wild Pan, the Panic Movement finally ended after an 11-year stint, with Jodorowsky disbanding the coalition after the release of Arrabal’s book “Le Panique”.

However, regardless of all the works in this time period, Jodorowsky and “The Holy Mountain” undoubtedly stole the show, being the most commercially, critically and artistically successful piece of the movement, and being the embodiment of all the violent, beautiful and surreal ideals that the Panic Movement stood for.

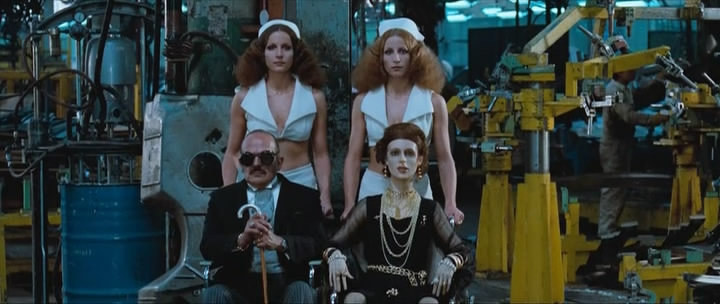

5. Vivid Surrealist Images and Scenes Throughout

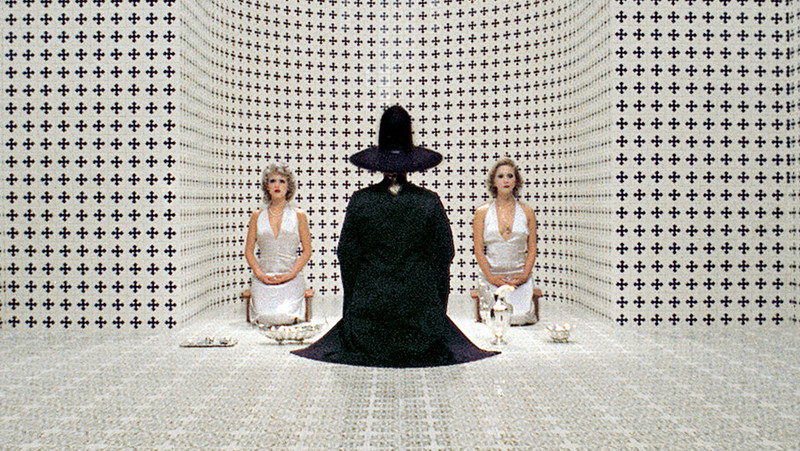

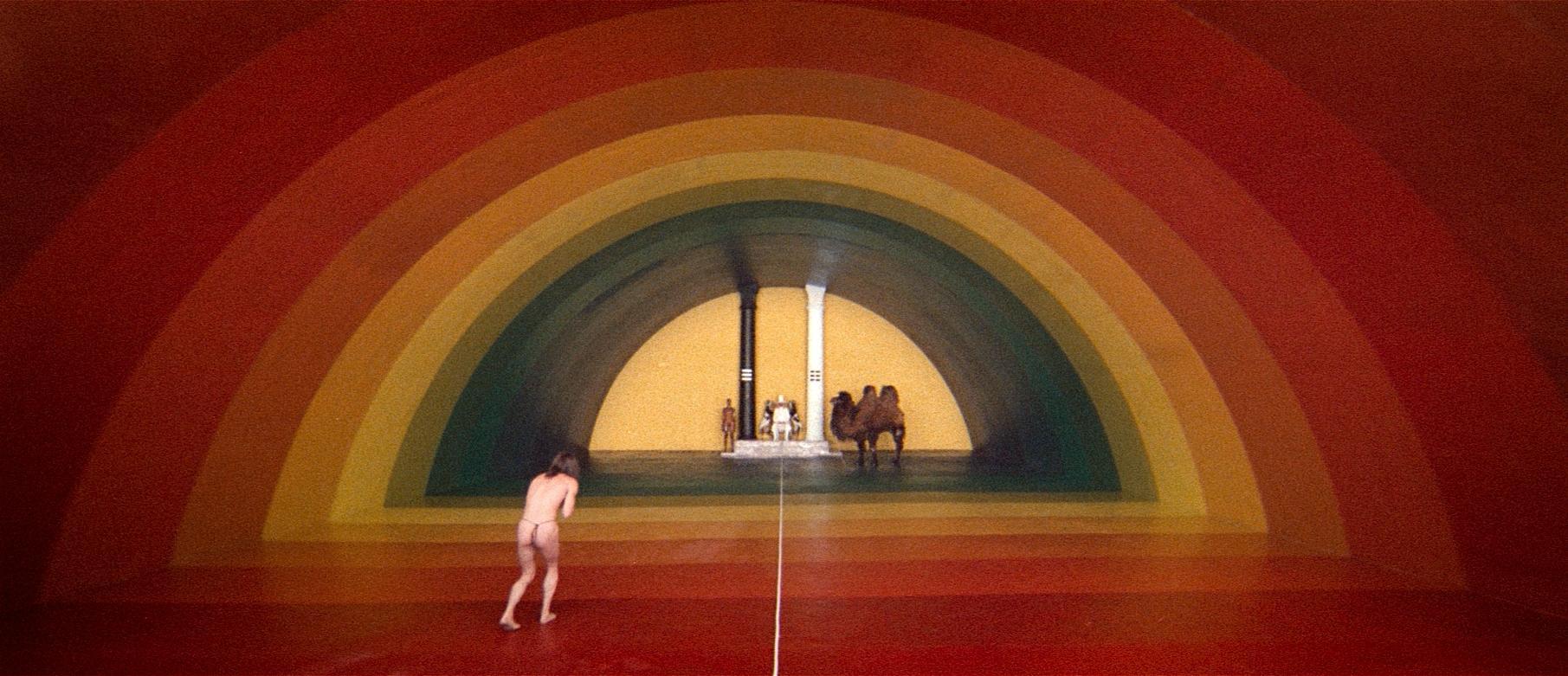

Most mainstream surrealist films, such as David Lynch’s “Blue Velvet” or Michel Gondry’s “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind”, use surrealism as a dramatic device, often intertwined with the plotline to create a difficult yet comprehensible final work that features bizarre characters, set designs and scenes. However, with a startling intensity, “The Holy Mountain” uses vivid surrealist images and scenes throughout the film, with every shot being crammed with strange actions from the peculiar characters Jodorowsky has created, including the venerable Alchemist.

It’s hard to pin down a few specific examples, as the vast quantity of fantastical action is simply visually overwhelming; however, a scene toward the end of the film, where each of the nine followers of the Alchemist have visions of their worst fears, is one of the most violent and provocative of them all. A screeching tumult soundtrack accompanies a naked man lying on the ground with tarantulas crawling over him, a man being pelted to death with money, a woman being symbolically raped with a fist – and this is only three of the nine visions.

The religiously controversial image of a Jesus-like figure eating waxwork figures of himself is another brilliantly executed piece of surrealist cinema, with the possible interpretations of both a thief appearing similar to Jesus, and then eating versions of himself being virtually endless. It would be wrong to simply read about the visual prowess of “The Holy Mountain”, as many of its surreal feats are ineffable through the medium of writing; it is a sensory experience from start to finish, and the only way to truly understand it is to immerse yourself completely in the aesthetic mastery of the film itself.