6. Lawrence of Arabia (1962)

It is so damn hard to pick between David Lean’s two biggest films: “The Bridge on the River Kwai” and “Lawrence of Arabia.” The latter only slightly wins, but you should definitely consider “The Bridge on the River Kwai” as well. The reason why “Lawrence of Arabia” takes the cake is simply because it achieved a rare trait in filmmaking: the creation of a mythos that feels tangible.

The vast landscapes, whether they be from Aqaba or Damascus, feel as though they are from a different world. The sand looks piping hot, yet beautifully carved like a sculpture (until they are crossed by men, however). The overtures lead you into the story through a grandiose orchestral score (composed by Maurice Jarre), and you start the film off with T.E. Lawrence’s death; you allow the rest of the film to tell you a story as a result.

What a story, indeed. Peter O’Toole’s breakout performance as the British officer Lawrence is extremely multifaceted. He is an outcast with goofy tendencies, yet he learns to take a stand; his clumsiness and recklessness turns into confidence and bravery. Whether his actions are commendable or debatable is up to you, and Lean’s film allows you that opportunity.

The film also grants you the chance to trek across the smoldering desert, and witness each crazy part of the story that transforms this one into a classic. While not entirely real (parts of the story, including characters, are fictitious), “Lawrence of Arabia” is still one of the finest films you may ever see. The Academy sure got it right with this one, and we may never see a film this zealous (four hours, with overtures and an intermission, too) and ambitious again (Hollywood likely won’t allow it).

7. The Godfather 1 and 2 (1972, 1974)

This may be considered cheating, but how can you include one Godfather film and not the other? “The Godfather” goes without saying: Francis Ford Coppola’s film changed cinema. It was the creation from what cinema could offer after the destruction of the Hollywood Code (a strict set of rules that major motion pictures had to abide by in order to be sold), as many films like “The French Connection,” “Midnight Cowboy,” In the Heat of the Night” and “Bonnie and Clyde” (three of these are also Best Picture winners) paved the way for it.

However, “The Godfather” took the taboos these films flaunted and turned them from art into poise. That doesn’t necessarily make it better (it depends on what you prefer), but it definitely had many other films follow suit. To have a film that benefitted from the complexities of the mafia and the gut-wrenching outcomes that occur within it? Yes, please!

The first Godfather film was a triumph, and the second is arguably even better (yes, I said it). Instead of settling for a weaker sequel or a dodgy prequel, Coppola put the two concepts together to create a solidly strong take on time and legacy. The Corleone family’s past involved the foundations of a young man seeking revenge (Don), and the present includes the crumbling of the dynasty that is begging to be fixed by Don’s heir (Michael).

“The Godfather: Part II” is even longer, and deliciously detailed. The first film played more with the dread of what doors death will knock on, whereas “Part II” is steeped in the looming fear of what comeuppance will happen to those we know will pay. Both films together are a gigantic feat that may never be replicated again in cinema (let’s not bring up “Part III”); they built upon the direction filmmaking was headed whilst expanding the horizon of where it could go next.

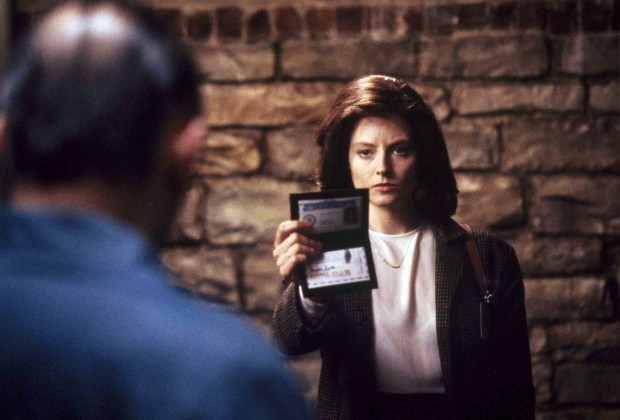

8. The Silence of The Lambs (1991)

The late Jonathan Demme pulled off a miracle in 1991 when it came to the Oscars. A horror movie (no film before or since has won), released early in the year (February, as most Oscar contenders get released toward the end of a year for consideration), which deals with brutal subject matter (serial killing, cannibalism and kidnapping, amongst many other things) won the top five prizes at the ceremony (Best Director, Adapted Screenplay, Actor, Actress and, of course, Picture).

This just does not happen at the Oscars, and yet “The Silence of the Lambs” achieved it. We know the acting (particularly by Jodie Foster and Anthony Hopkins) and the writing (by Ted Tally) is good, since they all won awards. How does the rest of the film hold up? How did a horror pull off the unimaginable?

“The Silence of the Lambs” is so enigmatically terrifying, particularly because most of it is the dread that comes from predicting what will happen. Demme expertly captures the realism of the situation, rather than trying to frame the film in a way to make it look haunted. The reality within the film is scary enough, from the way Buffalo Bill set up his house to the dampness of Hannibal’s cell.

The entire film is gripping, but I have to give the climactic showdown its dues for solidifying the film as a horror staple. The practice Demme had with his music films (especially “Stop Making Sense”) played into the choreography of this scene so perfectly, from the blaring music to the night vision power outage moment. A horror film has to be flawless to even be considered for Best Picture (unfortunately, that’s the way it is. Way less deserving films of other genres get picked up much more easily), and “The Silence of the Lambs” is just that.

9. Schindler’s List (1993)

I had ranked every Best Picture winner for each decade, and I had placed this film as not just the highest Best Picture winner of the 90s, but of all time thus far. Yes, I will boldly place this film over some of the classics that have won. Steven Spielberg’s name may be synonymous with schmaltz, overproduction and conventionalism, but I feel this is mostly due to his most recent catalogue of films, as there was a point where Spielberg used sentimentality correctly (“E.T.” is a great example).

However, “Schindler’s List” barely even feels like a Spielberg film for the most part, because it is mostly unrelenting with its take on its subject matter. “Schindler’s List” was definitely influenced by the harrowing depictions of horror from films like “Apocalypse Now” and “The Battle of Algiers,” as many of the more frightening scenes (and there are many here) feel almost too real to stomach (most of the gun-related executions still seem frighteningly authentic after many viewings).

“Schindler’s List” is shot and scored ambitiously, with each image and piece of music scaling the size of the horrors of the Holocaust without taking away from what you are witnessing. The story (about factory owner Oskar Schindler, who turns from a self-centered Nazi to the savior of more than a thousand Jews) is detailed and complex, to the point that it all makes sense. The hero is still flawed, but you can see when his change of heart occurs and how it all adds up relative to the situation and the character.

The film takes its time (definitely a benefit) to tell the story, so every miniscule detail plays into the bigger picture. There are many signs of terror, but also tiny glimpses of hope that keep this epic going. If you have not seen Schindler’s List for any reason (the length, content, or not being big on Spielberg), this is an imploration to witness a historical tour de force.

10. No Country for Old Men (2007)

When I ranked the Best Picture winners per each decade, I had a lot of flack from social media for the way I ordered these films. I got my head bitten off for ranking “Braveheart” the lowest of the 90s, and “Gladiator” the lowest of the 00s. The one reconsideration I had—and it was all thanks to you, dearest readers—was how low I ranked the Coen brothers thriller “No Country for Old Men.”

Comments left, right and center lambasted me for not ranking it first (or at least in the top three), and with some reevaluation, I can see why. I have been able to acknowledge how tremendously sharp and poignant this western is since I first watched it 10 years ago, and that has never changed. I may have placed it lower than it deserved due to my familiarity with it, but it is worth looking at with new eyes now that it has been 10 years. So how does it hold up now?

It was a Coen brothers opus then, and it still is. It is their darkest feature, one that blends awkward humour (a Coen brothers trait, for sure) with the inevitability of death. Death cannot be outrun, no matter who you are or what you do. The editing is viciously clean (the scene with the dog chasing Llewelyn is a highlight for this), the cinematography (Roger Deakins, ladies and gentlemen) takes advantage of the blisteringly hot landscapes, and the acting is subtle enough to be haunting (especially Javier Bardem’s Anton Chigurh).

All of these traits are based around a metaphorical heist story that tells more about the inability to stop evil than it does about a hot pursuit. The only thing I will mention here is that “There Will Be Blood” was also a contender for Best Picture, but could you go wrong awarding that prize to either film? “No Country for Old Men” is a Southern fable turned into a cinematic gem.