The dawn of the millennium ushered in a bumper crop of sci-fi films: with the overwhelming success of The Matrix, the genre was revived in popular culture with a new sense of purpose: to create reality-bending stories for audiences now primed to receive them. The nascent rise of the internet in the 1990s had since become a de facto part of Western culture and a new generation of tech-savvy citizens were looking to see what speculative fiction could be spun from the digital age.

Meanwhile, the familiarity of the genre also saw a deepening of the audience’s understanding of the history of science fiction in film, which spawned parodies and updates on classic tropes of the genre.

As such, science fiction once again entered the mainstream and has since become a mainstay in movie houses across the country. Perhaps by crossing the perceived goal post of “The Future” in 2000, the moviegoing population was hoping to catch a glimpse of what may come in our technological new age.

While not every movie on this list is forward-thinking (some rely heavily on past allusions to the genre while others were simply able to be made thanks to new technologies), many take a step forward in what the sci-fi functions as in Western culture. Whether social commentary, spoof, philosophy, or just entertainment, these are gems of the genre that you may not have seen from the first decade of this young century.

1. The Lost Skeleton of Cadavra (2001)

A mutant roams the countryside killing everyone it comes across after two aliens crash-land their spacecraft looking for a rare element atmosphereum to power their spaceship; a scientist and his wife go to the countryside to find a fallen meteor that holds that same element; and an evil scientist searches for the lost skeleton of Cadavra and–through its skeleton powers–seeks to rule the world.

The aliens disguise themselves as humans and (unsuccessfully) try to blend in, and the lost skeleton commands the evil scientist (who uses the aliens’ technology to turn four different animals into a woman) to do his bidding, which is to steal the atmosphereum from the scientist.

If it sounds like a bunch of old bad movies smashed into one, you’re not far-off: this sci-fi B-movie sendup sets out to exploit every possible cheesy trope evoked in old black-and-white low-budget films from a bygone era.

The performances are knowingly wooden, and the dialogue is wonderfully absurd, with lines such as “I’m a scientist: I don’t believe in anything,” “Even when I was a child, I was hated by skeletons!” and “The only person I want in that pretty little head of yours is me” delivered with amusing sincerity by the actors.

For those savvy in the sci-fi genre, particularly the bad B-movies that used to be spoofed on Mystery Science Theater 3000, it’s a gem of a comedy. A sequel was produced in 2009, creatively titled The Lost Skeleton Returns Again, which similarly follows the parodic tone of the original.

2. One Point O (2004)

After starting to receive one empty package after another, a computer programmer begins to have strange experiences: he’s constantly thirsty for a certain brand of milk, his neighbor is building an AI of some sort with a creepy head, and he’s being followed and surveilled everywhere he goes. In his grimy apartment complex, his neighbors are also experiencing strange cravings for particular food items and someone is going around murdering them.

This is just the short summary for One Point O (also known as Paranoia: 1.0), a cyberpunk sci-fi film that mashes a number of elements of the genre together to create a stylish and creepy story of the increasing paranoia that begins to consume the young man. With a solid cast (Udo Kier is particularly memorable as the android-building neighbor), an atmosphere of dread, and a claustrophobic, Kafkaesque story, One Point O should satisfy the tech-minded sci-fi fan–and even spook them a little bit.

3. The Final Cut (2004)

In an alternate reality where people have implants that record their entire lives, from birth to death, a Cutter–a person whose profession it is to edit a recently deceased’s memories into a memorial film–sees all, both good and bad, that a person had done in their life. In his work, he deletes the unsavory memories and cuts together only the positive ones to leave only a positive impression of the deceased for posterity .

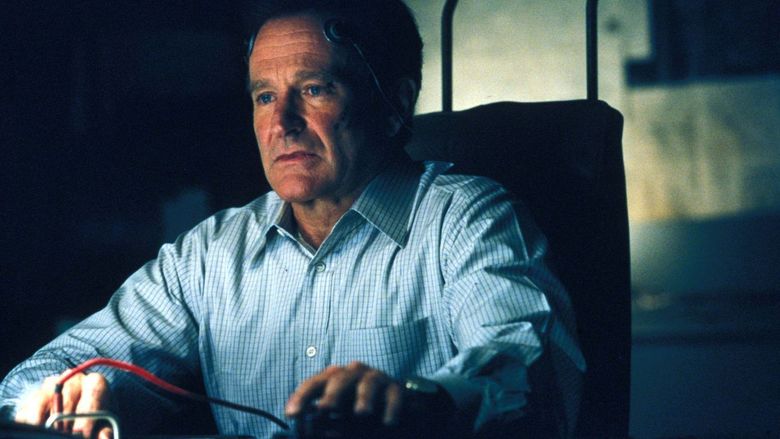

This film follows as one talented Cutter (played by Robin Williams) is pursued by anti-implant activists for incriminating footage from a wealthy businessman’s memories, which reveal that he molested his daughter. The Cutter also has a dark incident from his own past that he wishes to keep secret, but this may also be revealed as the pressure mounts and his personal and professional life falls apart.

Williams gives his trademark somber performance in this film as a man haunted by both his memories and the memories of others. The concept of an implant that records a person’s life may seem familiar to contemporary audiences, since the Black Mirror episode “The Entire History of You” employs a similar device in its plot. But The Final Cut is somehow darker than that notoriously bleak show, and it features a strong dramatic performance from the late Robin Williams.

4. A Scanner Darkly (2006)

Like many writers, Philip K. Dick was a sci-fi author whose work lives on long past him: since his death in 1982, a number of his novels and short stories have been adapted to film, including Blade Runner, Total Recall, and most recently The Man In The High Castle. Major themes and settings of his work resonate with modern audiences: dystopian states where the population is under constant surveillance, authoritarian governments, and the nature of identity and reality.

A Scanner Darkly works along similar lines: in a dystopian near-future, a powerful new drug, Substance D, has created an epidemic, with 20% of the population addicted. A deep-cover agent named Bob Arctor (Keanu Reeves) has infiltrated a group of addicts hoping to be introduced to a major supplier; however, he has also become addicted to Substance D in the process and the lines between his undercover life and his duties as an officer become increasingly blurred.

While the story itself is intriguing, it’s enhanced further by the vivid and stylized rotoscopy method employed, giving the film itself a disorienting and at times hallucinatory feel perfectly in line with the subject matter. Directed by Richard Linklater (who used rotoscopy previously in the similarly affecting Waking Life), A Scanner Darkly was a well-regarded, although not very popular, movie upon its release in 2006: but like much of Dick’s work, perhaps it was just a little ahead of its time.

5. The Wild Blue Yonder (2005)

Werner Herzog is an idiosyncratic talent: his filmography is littered with projects both novel and strange. From a feature film starring dwarfs (1970’s Even Dwarfs Started Small) to chronicling the downfall of a violent and insane conquistador (1972’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God) to piecing together a documentary of a doomed man that attempts to live with grizzly bears in the wild (2005’s Grizzly Man), Herzog is interested in capturing the odd, singular, and often futile attempts of mankind to transcend their place in the world, if not reality itself. A restless artist, Herzog jumps from subject to subject and genre to genre, always searching for the next novel story to tell.

The Wild Blue Yonder is as idiosyncratic a film as Herzog had ever made: an elliptical sci-fi story that’s pieced together from recontextualized documentary footage from various sources, adding a voiceover narration, and intercutting original footage.

Focusing on a character known only as The Alien, The Wild Blue Yonder depicts his struggle as an alien who came to Earth decades ago from his own water-covered planet, which has suffered an ice age, to form a community for his own people here. In another storyline, an exploratory mission is launched towards the aliens’ home planet to see if it will be habitable to human beings; when the astronauts return to Earth over 800 years in the future, they find the planet abandoned.

It’s as unique as any Herzog film, and his method of creating a visual narrative through existing footage is a bold experiment he repeats from his earlier film, Lessons of Darkness, which uses a similar perspective on Kuwait’s decimated oil fields after the Gulf War. The scope becomes global in The Wild Blue Yonder, where footage of our natural world–and the devastating effect mankind has had on it–underscore Herzog’s usual melancholic summation of humanity’s capacity for destruction.