5. Lake of Fire (2006, dir. Tony Kaye)

American History X marked the arrival of a talent by the name of Tony Kaye, but this talent would not unveil another effort for 18 years until the release of Lake of Fire in 2006, an emotionally shattering tour de force, as well as a fine blend of artistic cinematic expression and excellent documentary filmmaking.

Tony Kaye spent over 15 years covering the issue of abortion in the United States on both sides, which is the most important aspect of the film. As well as standing by abortion clinic protesters spouting, for some, pious and hateful rhetoric and some of the grisly murders they have committed against doctors, Kaye also unflinchingly examines the actual procedure of abortion being performed.

For two and a half hours, the viewer is subjected to the many different viewpoints on the issue’s spectrum – for some, it might be information overload. It is clear that Tony Kaye wanted to be as honest and unbiased as possible. Some might even say he doesn’t know how he feels about it.

Though some may argue that the film is less likely to change one’s opinion than reinforce it, Lake of Fire is nonetheless an extraordinary document of an important issue that demands at least one watch.

4. Love (2015, dir. Gaspar Noe)

With films like I Stand Alone, Irreversible, and Enter the Void Gaspar Noe has proven to be one of cinema’s most polarizing auteurs. With his latest film, Love, he proves that he will probably always be.

“I want to make movies out of blood, sperm and tears. This is like the essence of life. I think movies should contain that, perhaps should be made of that.” So states Murphy (Karl Glusman), a young American film student living in Paris, where he engages in a wonderful and highly sexual relationship with the voluptuous Electra (Aomi Muyock). Things become complicated, though, when Murphy impregnates their neighbor. Destroying his relationship with Electra, Murphy is first met living his life filled with boredom, longing, and regret.

Unlike his previous three feature-length efforts, which tend to have overall positive reception, Love resulted in an intensely mixed reaction from both audiences and critics. Perhaps they were too off-put by the highly explicit sexual content of the film (ironically, this is probably Noe’s most tame film as far as both content and style go).

While understandable, this is also very unfortunate, as the frequent and prolonged explicit sex pose an interesting question: is the great sex fueled by their passionate love for each other? Or is it the other way around? Before Electra and Murphy’s breakup, they experience some significant turmoil. They continue their relationship, but looking at them as they engage in intercourse, the passion steadily dissolves and appears to be replaced with desperation, as if these two characters have no other ideas as to how they can patch their relationship up.

Yes, the performances, while not terrible, left much to be desired, and Gaspar Noe’s self-insertion might be a bit too indulgent for some (the author would also like to note that he saw the film in 3D, which was insultingly not taken advantage of). All this said, the musings discussed above, combined with very reserved aesthetics from Noe – not to mention a killer soundtrack complete with Funkadelic, Pink Floyd, and Death in Vegas – Love is a hypnotic psychosexual odyssey that will hopefully one day be accepted in the ranks alongside Last Tango in Paris and Eyes Wide Shut.

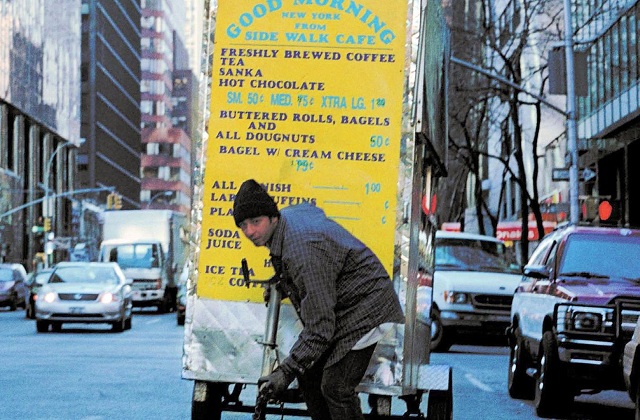

3. Man Push Cart (2005, dir. Ramin Bahrani)

If an audience member is only going to spend 1.5-2 hours with a character, is it appropriate to tell them that character’s entire life story up to that point? The best of drama is not in how much tragic backstory is revealed, but in how little, sometimes not at all. In 2005, Ramin Bahrani took this outlook to heart in Man Push Cart, as well as taking the blue-collar tragedy of Italian Neo-Realism and the urban grit of Mike Leigh.

Ahmad (Ahmad Razvi) wakes up in the darkened early hours of the morning every day, heaving his push cart to the streets of Manhattan, serving coffee and bagels to make ends meet. Or he’s refurbishing a wealthy man’s condo, who later recognizes Ahmad as a once famous rock star from his native land. Though his friendship with a fellow push cart clerk ease the weight of everyday life, Ahmad’s being is made only heavier, as all of his thoughts and emotions are focused on his estranged son, who is now under the care of his disappointed family.

What happened to Ahmad, a former music idol, to scrape by on a push cart? To be so alienated from his family? None of these questions are answered, and this is important to the film. Like real life, what has happened in the past has happened.

Instead of wallowing in the circumstances of the past, Ahmad accepts the consequences and perseveres, albeit day-to-day. Man Push Cart expresses great sympathy without asking for it from the audience, and does so without any mainstream contrivances. Ramin Bahrani’s documentary approach (many subjects didn’t know they were being filmed) only add to this exceptional Neo-Realist successor.

2. The Brown Bunny (2003, dir. Vincent Gallo)

With a prolonged display of graphic sex by a name actress, a notoriously disastrous screening at Cannes 2003 and a war of words between film critic Roger Ebert and Vincent Gallo, The Brown Bunny is now a film that is (and will probably always be) stuck in a permanent state of polarization, called by some one of the worst films ever made. Truly a shame, as Vincent Gallo has made a film that not only brilliantly transgresses the pornographic film, but has also exhibited a haunting meditation on loss, grief, longing, and loneliness.

Gallo is Bud Clay, a professional motorcycle racer. As the film starts, he has just finished a race and hits the road immediately following, where he seems to be haunted by memories of a lover by the name of Daisy (Chloe Sevigny). The two eventually reunite in a motel room in the controversial finale.

Once again, a film that is minimal in plot but massive in tone. Bud’s journey is a silent trek through the endless highways and open roads of the United States, and through this Gallo achieves an exemplary achievement in tone as the road trip is shown almost entirely from the interior of Bud’s van, giving the viewer a sense of confinement and isolation. Since the vast majority of the film takes place in this setting, those same feelings only become more resonant and unbearable – a rather brilliant way to offer empathy for the protagonist as he clearly has the same feelings.

Then there is the finale in the motel room. Though it is very explicit, with the tone the film has maintained up to this point, the scene is anything but erotic. Without spoiling the film, it provides the ultimate transgression on pornography and sexual fantasy: after all is said and done, there nobody/nothing there to fill that fetishistic void, only they who fantasize all at their lonesome.

Saying any more about The Brown Bunny would spoil crucial scenes, so it is best to leave it here and let the viewer experience the film for itself. Put the notoriety, the controversy, and Gallo’s questionable persona aside and view the film for what it is: a haunting cinematic experience.

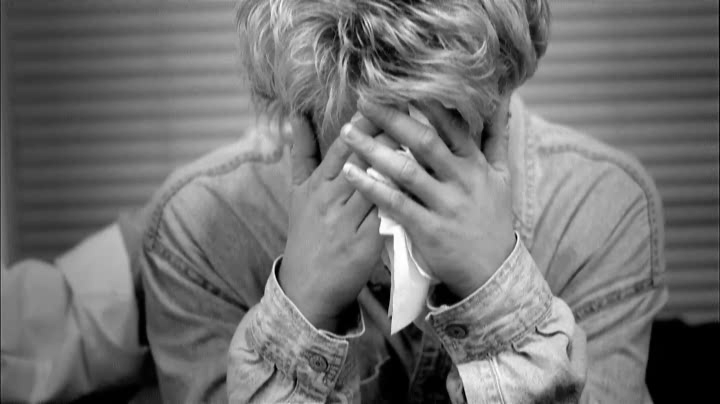

1. Secret Sunshine (2007, dir. Lee Chang-dong)

Following two landmark films of the South Korean New Wave – Peppermint Candy and Oasis – director Lee Chang-dong returned in 2007 with Secret Sunshine, a piercing portrait of one woman’s grief, new-found religious faith, and subsequent insanity.

Widowed Lee Shin-ae (Jeon Do-yeon) and her son have moved to the town of Miryang (her ex-husband’s hometown), perhaps looking for a fresh start. They settle in, wander about, get to know the locals, etc. Tragedy strikes: Shin-ae comes home one night to discover her son has been kidnapped, eventually resulting in murder. Grief-stricken, she eventually finds comfort in the Christian Church. She takes her religion very seriously, to the point where she visits her son’s murderer (confined in prison) to forgive him. He tells her he has also found faith in Christ. On her way out, Shin-ae collapses and descends into a downward spiral into mental illness.

The catalyst for Shin-ae’s madness is never vocalized in the film, and certainly up for debate, but it is in that confrontation with the killer that gives an interesting reason for her later behavior: when her son’s murderer extols the wonder in finding Christ, there is much sincerity in his voice.

If it is true, then he will surely be granted entry into Heaven, yes? After all, God is all-forgiving (according to the Christian doctrine anyway). Will he go to Heaven even though he has murdered an innocent child? It is through this that Lee Chang-dong has devised a piercing confrontation of religion’s frustrating complexity as strong as Breaking the Waves (fans of von Trier’s landmark film will find much to enjoy in Secret Sunshine).

While the subject matter makes this film interesting and engaging enough, Secret Sunshine’s power is only strengthened by Do-yeon’s performance, one that is strongly reminiscent of Gena Rowlands in A Woman Under the Influence – Do-yeon would take home Cannes’ Best Actress award in 2007. Though unfortunately not as fondly remembered as Peppermint Candy or Oasis, Secret Sunshine is still a strong piece of Korean cinema, and an unforgettable study in madness and faith.

Author Bio: Jakob Miller consumes oxygen in Tucson, Arizona, where he enjoys donning Tripp NYC in 100+ temperatures, practicing off-putting stoicism, and enduring Whitehouse at obscene volumes on a daily basis. He also likes movies.