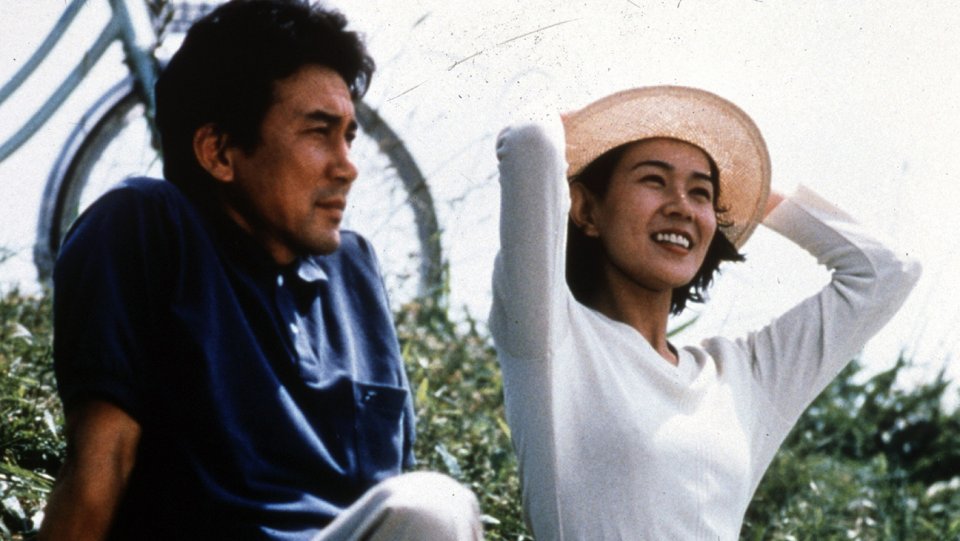

8. Through the Olive Trees (dir. Abbas Kiarostami)

The final film in Kiarostami’s trilogy about the Koker area in Iran (aptly named “The Koker Trilogy”), “Through the Olive Trees” follows a director making the previous film in the trilogy “Life, and Nothing More.” During the principal photography of the making of “Life, and Nothing More” one of the film’s actors falls in love with the lead actress, but because of the actor’s class and illiteracy, her parents find him unworthy, so she ignores any of his advances from then on.

Why it is essential: Like Kiarostami’s earlier and subsequent films, “Through the Olive Trees” blurs the line between reality and fiction. It is filmed in a natural manner, without obfuscating the verisimilitude of the film’s oblique story and plot. It is a great place to start if one is looking for their first Kiarostami.

9. Little Dieter Needs to Fly (dir. Werner Herzog)

Anyone who is familiar with “Rescue Dawn” should not be surprised by the incredible true story of Dieter Dengler, a Vietnam pilot whose attack aircraft was shot down by anti-aircraft missiles forcing a crash landing behind enemy lines in Laos, where hs is captured and tortured while tied to a bamboo cage.

Why it is essential: To really put the ordeal into perspective, Dieter takes Herzog through a tour of his encampment and route of escape. It is no surprise that Herzog felt compelled to turn Dieter’s tale of survival into a feature-length film. The courage and willpower he had is truly inspiring. In fact, this may be the only time Herzog has adapted one of his documentaries into a narrative feature. That just means how moved Herzog was by Dieter’s story.

10. Time Regained (dir. Raúl Ruiz)

Elliptical storytelling at its finest. Ruiz crafts a ludicrously gorgeous adaptation of Marcel Proust’s final volume of “In Search of Lost Time” about Proust lying on his deathbed recalling his past experiences as a young man. We follow his memories through heartbreak and triumph.

Why it is essential: The magnificent production values alone are worth just seeing the film. The details adorning the sets and costumes make the each location come alive. But it is a dense film, it is very formalistic (veering into the avant-garde). However, “Time Regained” is immensely rewarding for anyone with a strong attention span.

11. The Color of Paradise (dir. Majid Majidi)

A somber film about honesty and acceptance, a blind school boy named Mohammed takes leave for summer vacation, but his father is too ashamed of his son’s disability and tries to convince the headmaster to keep the child over the summer break. The principal refuses so Mohammed’s father reluctantly takes him back home.

Why it is essential: The title of the film has nothing to do with any physical paradise per say, but of a mental state. Mohammed has most likely been blind his whole life, so experiencing some kind of visible color would be the equivalent of paradise for him, it would be like witnessing God for him. Also, spirituality plays a central role in the film as God is referenced throughout as a beacon of hope.

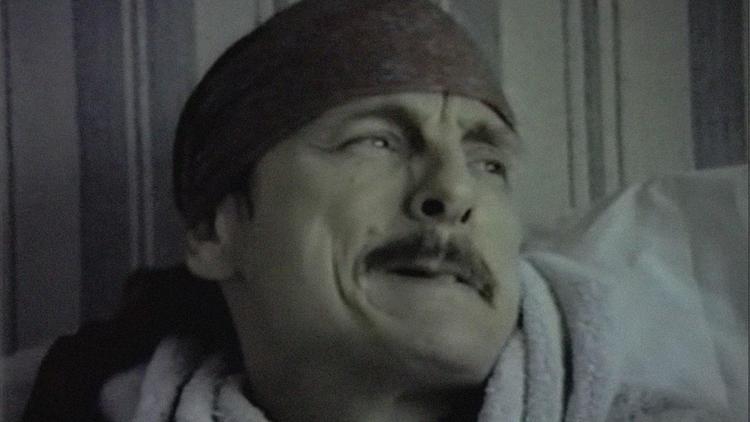

12. One Day in the Life of Andrei Arsenevich (dir. Chris Marker)

Marker had a fair amount of success with his documentary profile on the legendary director, Akira Kurosawa called “A.K.” Here Marker points his erudite eye onto Andrei Tarkovsky focusing on his philosophies, filmmaking style and final days on Earth.

Why it is essential: If there was anyone who is a fan of not only Chris Marker, but of Andrei Tarkovsky as well, then this is a must see documentary. Marker takes us through some of the behind the scenes events in “Offret.” Showing how Tarkovsky works with his crew, and detailing how Tarkovsky shot the burning house in the climax of “Offret.”

Tarkovsky passed away in 1986 at only 54 years old due to terminal lung cancer. “One Day in the Life of Andrei Arsenevich” acts as a respectful and beautiful eulogy to this icon.

13. A Moment of Innocence (dir. Mohsen Makhmalbaf)

A dramatization of two events: the stabbing of a policeman by an Iranian revolutionary (Makhmalbaf) and that same revolutionary making amends with the cop two decades later. Both the cop and Makhmalbaf play themselves as they try to recreate the events that lead to the assault. Hiring local kids to play them when they were adolescents/young adults.

Why it is essential: Surprisingly funny for its subject matter, the film’s title is a contradiction of the events surrounding the assault. There is nothing innocent about Makhmalbaf’s intentions. Though what was innocent was that part of Makhmalbaf’s plan to get the gun from the cop was to use his cousin to distract him but the policeman inadvertently forms a crush on her.

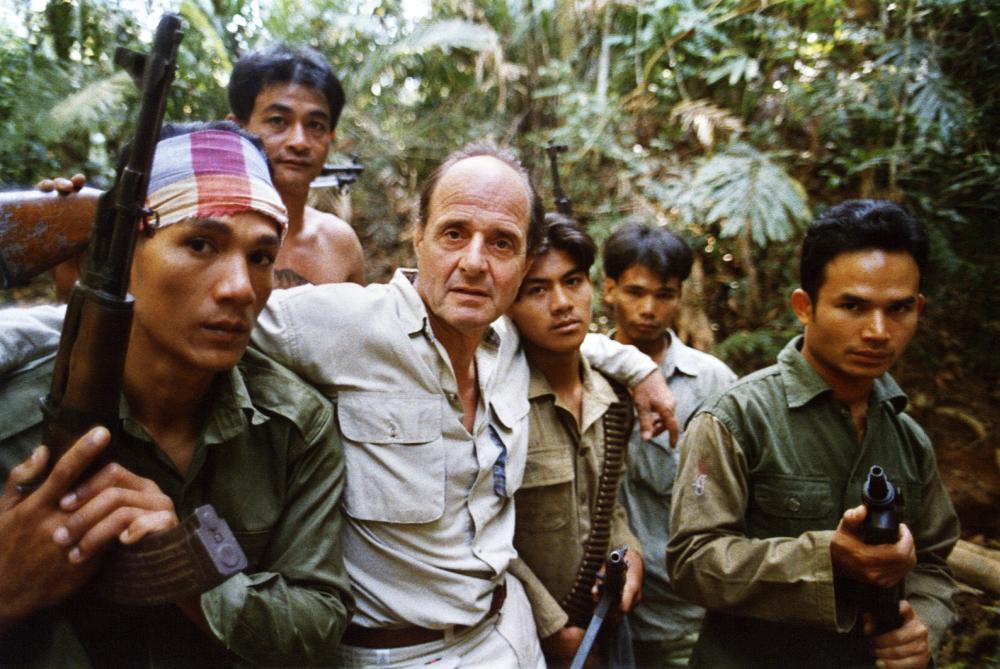

14. The Eel (dir. Shohei Imamura)

It is difficult to think of another film that begins as bleak and hopeless as “The Eel” only to end up making life feel worth fighting for. Maybe “The Shawshank Redemption” comes to mind, but with “The Eel” the husband actually did it. Takuro (Kōji Yakusho) gets a tip from an anonymous note saying his wife is having an affair with another man when he goes fishing.

He acts upon the note and returns home early to settle his fear, but in a passionate, blind fury he brutally stabs the couple when the prophetic note tells the truth. Leaving his home drenched in blood he bikes to the nearest police station, turning himself in.

Why it is essential: Ostensibly a somber look at depression and loneliness, “The Eel” is simply a film about reconnecting with people after tragedy. Possibly the hardest tragedy to shake off being murder, but the woman Takuro meets after being released from prison gives him hope even if he does not notice her right away.

15. La Cérémonie (dir. Claude Chabrol)

Chabrol was one of the few French New Wave directors to work heavily in genre-pictures, more specifically thrillers. In this thriller, we witness a young woman named Sophie Bonhomme (Sandrine Bonnaire) crumble under the pressure and class difference her new job as maid brings her.

Why it is essential: Sharing themes with a senegalese film, “Black Girl,” both protagonists in each film are given well paying jobs, but the inherent differences socially and economically between themselves and their employers begin to show their teeth. Both women take drastic, albeit melodramatic, steps in terminating their employment.

Although, the main difference between both maids is that Sophie has proven to be an unreliable employee: she can not read, she is irresponsible and may have a history of violence.

Author Bio: Dajoune Rogers is a college student in Sacremento, California majoring in Film. He spends most of his free time reading and watching at least 3 films a day. He has an active a micro-blog on Instagram, @film_literacy.